Pop culture is having a John Carpenter moment. Earlier this year, reviews for Jeremy Gillespie’s horror film The Void excitedly described it as “Carpenteresque,” the same phrase that writer-director Jeff Nichols used to describe his acclaimed science fiction thriller from last year, Midnight Special. Sci-fi and horror films are suddenly awash in the steely light-blue shroud that was the trademark look of Carpenter’s early films four decades ago.

Normally, it wouldn’t be surprising to see a director with a filmography like Carpenter’s acknowledged as hugely influential. But for some reason, it’s always taken a long time for Hollywood to catch up with him. Even his 1978 breakthrough film Halloween—the low-budget tale of mysterious killer Michael Myers that changed the industry forever by becoming the first megahit indie movie—was dismissed by most critics. Today, of course, it’s considered one of the best horror films of all time, and it has lost none of the power that enthralled its first audiences. If anything, Carpenter’s empathetic and realistic depiction of the teenage girls who face off against Myers (including, most famously, Jamie Lee Curtis) has made it stand out even more over the years from the hundreds of imitators that have come in its wake.

The same pattern of initial critical hostility overcome by appreciative audiences—followed, eventually, by a full-on cultural lovefest—emerged with most of Carpenter’s best films, from his 1974 debut Dark Star (originally his student film at USC) to his 1976 pioneering siege movie Assault on Precinct 13, through 1980’s The Fog, 1982’s The Thing, 1983’s Stephen King adaptation Christine, 1986’s Big Trouble in Little China, 1987’s Prince of Darkness, 1988’s They Live and 1995’s In the Mouth of Madness. Incredibly, all of these films recovered from their initial critical write-offs to find cult followings and go on to be considered classics. (Only his two warmest and most immediately accessible movies, 1981’s Escape From New York and 1984’s Starman, truly got their due right out of the gate.)

At the same time, thanks to the fact that Carpenter composed the pioneering electronic scores for most of his own movies, “Carpenteresque” has also become a popular adjective in the music world. Music journalist Aaron Vehling described it earlier this year as “the go-to descriptor for dark-tinged, arpeggiator-heavy synth scores.” Just this month, Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails and Atticus Ross released a cover version of Carpenter’s famous theme for Halloween, becoming the umpteenth musicians to do so over the years. While it is most often covered by goth-type bands like Electric Hellfire Club and Celldweller, it’s also been tackled by artists as eclectic as cellist Tina Guo and German classical guitarist Leif M. Schaffland.

In the last few years, Carpenter has embraced his musical legacy, releasing his non-soundtrack debut album Lost Themes in 2015, which he recorded with his son Cody Carpenter and his godson Daniel Davies. Lost Themes II followed the next year, and remarkably, critics didn’t have to take their time coming around to either record; both received positive reviews for staying true to—and building on—the electronic sound of Carpenter’s movie music.

This year, Carpenter is revisiting his original scores with the release of the Anthology: Movie Themes 1974-1998 album and the subsequent tour that comes to the Catalyst on Sunday, Nov. 5. (In a well-timed Carpenter tie-in, the Midnights at the Del Mar series will be presenting The Thing on Friday, Nov. 3, and Escape From New York on Saturday, Nov. 4.) He even directed a music video for “Christine” that recaptures the atmospherics of the movie, with the sinister steel of the iconic car set against chilly, dreamlike streets.

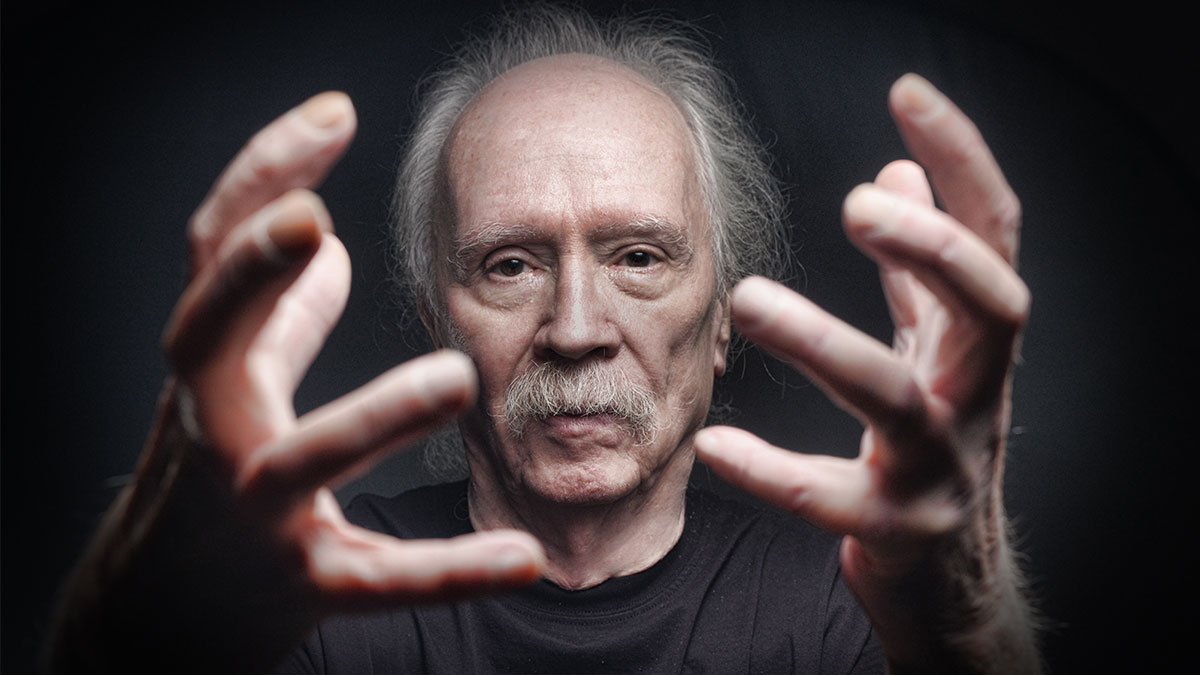

I spoke to the 69-year-old Carpenter last week by phone about his current tour (on which he is backed by his son and godson), and discovered that pretty much the only person who doesn’t put much stock in John Carpenter’s immense cultural influence is John Carpenter. Self-effacing and seemingly somewhat ambivalent about his own work, he was, for instance, skeptical about my insistence that “Carpenteresque” is really a word that people use. Put in the somewhat odd but very entertaining position of having to prove to one of my favorite directors that his stock is at an all-time high, I pulled out my ace in the hole, reading to him from the transcript of a recent interview I did with Matt and Ross Duffer, the creators of the Netflix show Stranger Things—which is certainly one of the hottest zeitgeist properties out right now. The Duffer brothers’ love of all things John Carpenter is fairly well known, but in particular I read him what Matt told me about why the character of Mike has the movie poster for The Thing in his basement on the show: “Even though it would be pretty much impossible for that poster to be in the boy’s basement, we put it in there anyway. You can see it when they’re playing D&D. Oh man, we were obsessed with that movie when we were in high school. There’s something about the creature design. I don’t think anyone’s been able to pull it off as successfully since. That’s the scariest creature design. The fact that they did that in camera is incredible. We did strive to do as much as we could in camera, and we couldn’t get close to achieving what they achieved. It really makes you respect those guys and what they were able to pull off.”

I know that ‘The Thing’ got a lot of flak when it came out. Does it feel like a vindication to hear a quote like that from the makers of one of the biggest pop culture phenomena of the last couple years?

JOHN CARPENTER: That’s very, very nice. It feels great. I can’t think of one thing that’s wrong with that. (Laughs.) Look, I took a lot of shit for that movie. But I kind of know why, I think. Because what I did not put in that movie was any hope. And audiences and critics, that’s what they needed back then. They needed hope, and I just cheated them of it. So I’m a bad guy.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen popular opinion of a movie do a complete 180-degree shift the way it did with your version of ‘The Thing.’ Reviewers were so hostile at the time, and now it’s revered almost universally as one of the best movies of the ’80s.

I don’t understand why it did that turn. Do you know?

Well, it’s a great movie. Maybe pop culture just had to catch up with it. And now it has a huge fan base, as do most of your films that a lot people didn’t seem to get when they were released. One of my favorites from that time is ‘They Live,’ which I think is one of the best political films of the ’80s.

Well, thank you. That one was a lot of fun, we had a good time.

I remember someone asking you around that time if the fascist aliens were a metaphor and you said something like, ‘No, they’re Republicans.’

Yeah, well it’s true! I mean, come on now! I was enraged at the time, I had to make this political statement. So I did it under cover of a teen science fiction movie. Plus, we got to have this big fight.

Oh man, yeah, that fight. And now the line “I’ve come here to kick ass and chew bubblegum, and I’m all out of bubblegum” is quoted all the time.

I know! It worked out alright for us.

Did an awareness that these films have found big cult followings have anything to do with the timing of the ‘Anthology’ album and tour?

My son and godson and I, we realized last year when we were playing concerts around the world that what audiences really loved was the movie music. So I thought, why don’t we do an album of movie music? I mean, why not? And here we are. Anthology is an album that encompasses my movie career from the ’70s to the ’90s. It’s scenes from my films that were chosen for various reasons. We also re-recorded music from Jack Nitzsche and from Ennio Morricone. So it’s not just me as a composer, but others, too. So we’re going to play that live—attempt to play it live.

Are you going to show the scenes from the film while you’re playing it?

Yes, we are.

What’s the difference for you between playing these themes live and recording them in the studio?

Well, they’re both great, but I get to work with my son and godson on this. And I’m telling you, there’s nothing like it. I didn’t ever think I’d have the chance to do this. Daniel, my godson, is a guitar virtuoso, and my son is a keyboard virtuoso. So I’m just in the middle, playing really simple stuff and dancing around and being happy. That’s my job.

You did once say, ‘I can play just about any keyboard, but I can’t read or write a note.”

That’s the way it is. It’s true. I know my own worth as a musician—I have limited chops.

Does that have anything to do with why your music sounds different than other composers’ work?

I don’t think so. It just means I have my limitations, and they’re very obvious to most people.

You feel more confident as a director?

Confident? Ehhh, well, it’s all kind of equal to me. In other words, what I do as a director and what I do as a musician are very similar. I’m just the luckiest human being on the earth. Because I’ve been directing for many years, and I do love cinema, but I get to have kind of a different career—late in my life. And it’s fabulous.

You have music videos now!

Oh stop, ha ha. Yes, I do. I directed one. It’s true.

I enjoyed how the video for “Christine” was clearly done not just for people who might be discovering your music, but also for your movie fans who will recognize a lot from the film.

Well thank you. I had a great time making it. It was really fun. Although I had to stay up all night, which is a little tough. Several months ago, we were talking to someone in advertising or something, and they said, ‘You know what you ought to do is make a video. Not a music video where you’re performing, but a story video.’ And I thought, ‘Wow, OK.’ So we talked about it, and the first thought we had was, ‘Let’s do Christine stalking somebody.’ And it just worked from there.

When you were putting together ‘Anthology’ and going back and listening to soundtracks of yours that you maybe hadn’t listened to for a while, what surprised you the most?

Well, I now know—and don’t ask me what it is, because I’m not going to tell you—what my musical signature is. I discovered it, and I went “Oh really? That’s it? Really! How disappointing.” But I now know what it is that I relied on to get me through when I was doing this music. So that was interesting. But I really truly enjoy a lot of the music that we play. It’s fun. Some of it’s scary. The theme from Starman is much more hopeful and sweet, and we did one of those. A lot of it rocks out, I have to be frank with you. The rhythm section of the group I’m playing with is Tenacious D’s rhythm section. They are unbelievably great.

How’d you hook up with the guys from Tenacious D?

Daniel knew them, and hung out with them a bit. He loved how they sounded and the kind of stuff they did, so we all got together. We’re having a blast.

The soundtrack to ‘Halloween’ was really what put you on the map as a composer. I’ve read about what the initial response to the movie was like, but I’ve never heard anything about the early reaction to the music. Did anyone realize that it was going to go down as one of the most famous horror movie themes of all time?

No. God, no. They didn’t pay any attention to it. It was just on the movie, and everybody accepted it. Nobody said anything to me about it, necessarily, so I thought, “OK, as long as they don’t throw shit at the screen, I’m happy.”

That was an era when composers were doing a lot of epic, sweeping scores—John Williams’ ‘Star Wars’ and ‘Superman,’ Jerry Goldsmith’s ‘Star Trek: The Motion Picture.’ Of course, ‘Halloween’ was a very different movie, but was the intimacy and rawness of the theme a reaction to that at all?

No, it was absolutely functional. Because I came from student films, and this was a low-budget movie. Low-budget movies and student films, they don’t have any money. They don’t have enough money to get an orchestra or a composer. So somebody who is cheap and fast has to do the music. And that’s me. Halloween took three days for the score. I did five or six pieces, and then cut them in at various places in the movie. We didn’t have any more money than that.

Now all of these darker goth-type bands love to cover your music, especially the ‘Halloween’ theme. Has that surprised you? Did you ever expect to be a goth icon?

Ha, well, I don’t know about that. But it always surprises me when something of mine shows up. I’m just delighted by it, it’s great.

There are a lot of those covers now. I’m sure you know that.

No, not particularly. That’s something else you have to realize about my career: no one tells me anything.

When you did the ‘Lost Themes’ albums, was it to get a little bit of freedom to compose without having to base the music on the visuals of a film?

Well, you know what, I should say yes. Or I can tell you the truth.

Oh, I definitely pick the truth!

OK, well, the truth is that ‘Lost Themes’ is an extended improvisation with my son and I playing. We’d play video games, we’d go down to the music room and improvise a little music, come back and play video games, go back and improvise a little music. This went on and on for a while, so I had a whole bunch of music. He went off to Japan, and I was hanging around here, and I got a new music attorney. And she said, “You got anything new?” I thought, “Well, I have this stuff here,” so I sent it to her. A couple of months later, I had a record deal! What the hell is that? That’s what happened. I didn’t plan it.

What’s it like to see your work and influence rise and fall over the years, and then all of a sudden have it rise sharply like this?

It’s bewildering. I mean, I don’t know why. But I’m trying not to ask. Just go with it. Just go with the flow, that’s all I do.

JOHN CARPENTER performs at 9 p.m. on Sunday, Nov. 5, at the Catalyst, 1011 Pacific Ave. in Santa Cruz. The show is 16 and over; tickets are $39.50 and up. Catalystclub.com.

The Midnights at the Del Mar series will show Carpenter’s ‘The Thing’ on Friday night at midnight, and ‘Escape From New York’ at Saturday at midnight at the Del Mar, 1124 Pacific Ave., Santa Cruz.