Subdivided We Fall

California today finds itself at the helm of a relatively stable, if embattled, environment. But will the sheer crush of population growth and its added demands send the Golden State into an ecological tailspin?

By Christopher Weir

TAUNTED BY ROILING SMOG, terminal drought and an explosive population, eco-prophets predicted an imminent environmental collapse. Industrial toxicity would irreversibly sabotage vital natural resources, and subsequent human desperation would push nature to the breaking point. It was a nightmare in the making.

It was California, circa 1976. But the Golden State--weaned on earthquakes and baptized by firestorms--was prepared to stare down the double barrel of its self-destruction. Readily confronting its unsustainable sins, it initiated what has since become the most innovative body of environmental protection measures in the nation. So today--20 years into that once-dismal future--California's ecological shape of things is far from apocalyptic.

And yet, the state's environmental stress continues to mount amid the pressures of suburban sprawl and drain on resources, a trend that shows no sign of abatement. If California is indeed going to hell, it will be a slow, measured descent.

What's clear is that the fate of California's complex ecological circuitry will be increasingly plagued by tough choices. Resource consumption and land-use rights will continue to ignite ferocious debate, and discussions on population growth will shift away from immigration politics and hinge instead on whether or not the land will be able to handle the mounting masses.

Noting that California's population is projected to balloon from 33 million to a bewildering 49 million by 2020, the state's most recent Water Plan Update warns of "frequent and severe" water shortages if successful conservation and reclamation measures fail to materialize in the next decade. Such warnings imply that the health of wetlands and river systems may ultimately be compromised, even more than at present.

Meanwhile, the state's millennia-old virgin redwoods have nearly been eradicated by less than two centuries' worth of opportunism. And a vast network of forests, woodlands, grasslands and deserts remains endangered by entrenched mismanagement and high-octane suburbia.

"I think it's very important that people in the state realize that California has a lot more to lose than virtually anyplace else in the country," says Reed Noss, acclaimed research scientist and editor of the journal Conservation Biology, in reference to California's unparalleled ecological diversity.

Noss, who co-authored a report that places eight of the nation's 21 most endangered ecosystems in California, adds, "We're really cutting off our life-support system. ... We're paying the price already, and it can only get worse in the future unless we turn things around."

To do that, Californians must confront the vortex of their natural resources and envision an environmental future fraught with uncertainty. More than 90 percent of California's original old-growth forests are history. The state's riparian zones have been visited by similar decimation, and vast ponderosa pine forests from the southern Sierra Nevada to the North Coast increasingly resemble a sickly tinderbox.

Twenty-two million acres of native grasslands have been paved or denuded. Oak woodlands, the symbol of California's sturdy individualism, are in the throes of devolution. And the southern deserts slowly recede into suburban oblivion. "What it's creating is a less interesting, less stable world," Noss says. "We already have abundant evidence of declining productivity, most of which is related to poor land-management practices."

Forests Tuckered

AMONGST THESE practices is the "forest as a renewable resource," a theoretical concept that has engendered some troubling realities. In the Tahoe Basin, for example, unstable forests and whacked-out ecosystems are the direct result of clear-cuttings dating back more than a century.

Today, the Tahoe Basin boasts forests that are, in the words of California's forestry director, "80 percent dead." Logging-related erosion and dense understories have dispersed essential soil nutrients, a situation exacerbated by Smoky the Bear zealousness that has denied the mineralizing nourishment bestowed by fire. And fir -engraver beetles are on parasitic holiday, their gluttony stoked by the unnaturally high component of firs that asserted themselves in the wake of clear-cuts. The result: vertical phantasms that are, collectively, an ungodly firestorm in the making. The human and environmental costs of the coming inferno are difficult to predict.

This scenario, which is being actualized in varying degrees throughout California, has given rise to a new concept: logging as savior. And it's a concept that is gaining increasing momentum in the wake of the recent fire season's startling ferocity. While 150 fires raged throughout the west during August, a coalition of timber industry officials claimed that reduced harvests were largely responsible for the extreme fuel load. Salvage logging--the removal of, in theory, only dead and dying trees--was the implied solution.

Environmentalists, however, maintain that salvage logging is merely a disingenuous maneuver to reinvent the ailing timber industry's destructive practices.

This notion was reinforced when the "timber-salvage rider" was affixed to a portion of the 1995 federal budget package. Among other things, the law directed federal agencies to "reduce the back-logged volume of salvage timber" and exempted related projects from several existing environmental review procedures.

A $7 million federal study conducted by the Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project--a panel of 107 university, state and federal scientists--recently concluded that salvage logging has contributed to fire hazards by generating combustible debris and reducing forest-cooling canopies. Other related issues involve erosion-induced watershed fouling (forests and rangeland carry more than 90 percent of California's water runoff) and habitat destruction.

Yet, when the Clinton administration trashed a recent proposal by the Forest Service to increase Sierra logging loads by 50 percent, several of the project's scientists supported the Forest Service's determinations and maintained that the proposal was sufficiently mindful of their study's ecosystem-management recommendations.

Whether or not sustainable and responsible logging can coexist with long-term environmental goals is a matter of fierce and continued debate. Some observers even suggest that logging could be the lesser ecological evil in a culture that demands land use in one form or another.

Noting that population analysts expect the Sierra Nevada to be within a day's drive from 65 million people by 2040, UCBerkeley regional planning scholar Timothy P. Duane recently told the Los Angeles Times, "We have no idea what the carrying capacity of the land is. We can't say that, in the end, a well-managed, sustainable timber operation won't be easier on the land than mass recreation."

Certainly, California's forests are at a social and ecological crossroads, and their future will depend largely upon policy decisions forged within our lifetime. And if those decisions are the wrong ones?

"We're in danger of losing some of these ecosystems--some of these forest types--altogether," Noss says. "For one, it's a loss of our natural heritage. As for the long-term repercussions, we don't really know yet. Whether or not [replacement] systems will be able to function as well in terms of protecting watersheds, buffering air pollution, producing oxygen ... we really can't say."

Water Torture

AS WITH CALIFORNIA'S forests and woodlands, air quality and water supplies remain threatened by developmental and population forces that defy simple solution. Overall, state air quality continues to improve, yet the borders of destructive air pollution continue to expand. Meanwhile, demand on water resources could outpace supply in the near future. Ensnared in these conundrums are embattled--and some would contend vital--ecosystems.

The rancor between California's urban and rural water interests became legend when Owens Valley renegades dynamited the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1924. Since then, the relationship has remained tenuous, prompting accords that, while satisfying cities and agribusiness, have taken a significant environmental toll. For example, the Sacramento River Delta--the source of 20 percent of the state's water--is suffering from devastated habitats, erosion and saltwater intrusion, developments that are now being addressed by the CALFED project.

The state's water plan, established in 1957 and updated every five years, is charged with the formidable challenge of meeting and managing an ever-increasing demand for water. And the most recent update hints at future water wars ignited by population growth and exacerbated by environmental concerns.

"What we said in the last update," says Naser Bateni, an engineer with the Department of Water Resources, "was that because of an increase in population, and because of increased allocation of water to environmental uses--fisheries resources and wildlife refuges--we're going to have a shortage of water by 2020. The shortages during a drought would be seven to nine million acre feet. To put that into perspective, the total state urban water use--industrial, municipal and residential--was about seven million acre feet in 1990."

While the update offers suggestions for improvement, it's unclear whether or not California can slake the thirst of 50 million people without unraveling environmental priorities and crippling habitat restoration efforts.

On a more encouraging natural-resource front, state air quality continues to improve in response to vehicle emissions controls and regulatory accords, such as PG&E's $20 million pledge--made under pressure from the Monterey Bay Unified Air Pollution Control District--to reduce by nearly 50 percent the nitrogen oxides exhaled by its Moss Landing gas-fired power plant, the largest single-source air polluter in a three-county area.

"California's air quality has improved dramatically in the past 25 years," says Allan Hirsch, an information officer with the state's Air Resources Board. "In 1970, there were 148 first-stage smog alerts in the greater Los Angeles area. Last year, there were only 13. In 1969, the Bay Area had 65 violations of the federal ozone standard. In 1992 through 1994, it only averaged one ozone violation."

According to Air Resources Board estimates, emission inventory trends suggest a continued decrease throughout the 1990s in most of the pollutants contributing to violations of ambient air quality standards. The impact of population growth, however, is expected to halt, and possibly reverse, reductions of nitrogen oxides and reactive organic gases in coming decades.

And while these inventories show an overall reduction pattern, air pollution launched by sprawling growth is forging a destructive path through distant and sensitive ecosystems. Ozone generated by the Central Valley and other urbanized areas, for example, is weakening pine stands on the Sierra's lower-elevation western slopes, especially in the area of Sequoia National Forest. Crippled growth, premature defoliation and susceptibility to parasites are the increasingly incendiary forest symptoms that are traced to ozone migration.

"Obviously, we still have a ways to go before we really have clean air," Hirsch says. "With California's population growing, and with vehicle miles traveled growing, we still face a significant challenge in getting emissions down."

California's crown jewel, the Sierra Nevada, is expected to undergo three-fold population growth within 50 years. In some pockets of the Sierra and its foothills, the air is among the state's dirtiest, a development that promises to worsen. Two-thirds of the natural water systems are degraded. Strip malls and subdivisions sprout like chickweed, wildlife is in decline and overgrazing continues to push rangelands into unsustainable oblivion.

It may sound like the Los Angeles of yesteryear. But the aforementioned federal study concludes that today's Sierra Nevada bioregion--home to a broad network of unique habitats and ecosystems--faces significant and "irreversible" ecosystem loss if progressive restoration and protection measures are not implemented in the near future.

"I think there's a growing consensus that action is due," says Andy McLeod, California's deputy secretary of resources. "People aspire for the study to be various things. What I think it has to be, fundamentally, is a tool that the region's counties use to plan their future, and to make long-term decisions about resource use."

The plight of the Sierra Nevada, unfortunately, is not unique. Says Superintendent Ernest Quintana of the Mojave's Joshua Tree National Park, "We used to be a little area off in the desert, seldom visited, little development. Now the Coachella Valley to the south has boomed, the Morongo Basin to the north is developing, and air pollution coming in from the urbanized inland empire is an increasing threat to the park. Hopefully we'll realize that what we do in one region is directly tied to and will impact other regions."

Population Bomb

CALIFORNIANS HAVE, of course, been hearing similarly articulated concerns for the past 75 years. What's different now, however, is that these concerns are resonating through many of the state's final frontiers. Beyond these, you're not talking California, but Nevada and Arizona.

Consequently, critics of some frontier-region counties charge them with not adequately integrating their development patterns within a larger ecosystem context. Others counter that outsiders shouldn't be able to deny such counties the economic benefits of developmental forces that have shaped other regions.

Californians have good reason to be terrified of their own potential to pave or otherwise transform landscapes. Consider, for example, that 50 years ago Los Angeles County was one of the most productive agricultural areas in the nation.

Ultimately, then, Californians as a whole may have to decide whether or not such regions as the Mojave and the Sierra Nevada will occupy sacred territory in the state's natural heritage and environmental future. Restricting regional development based on such determinations is not without voter precedent.

In 1972, for example, Californians passed Proposition 20, which established developmental constraints for coastal zones. The Legislature followed in 1976 with the California Coastal Act, which forged a system of coastal-zone protection largely responsible for keeping large portions of our shoreline undeveloped.

As an investment, this preservation policy has yielded considerable and multi-faceted returns. Noting that economic productivity in California's coastal zone generates 56 percent of the gross state product, and that 86 percent of the state's tourism-related outlay is spent in coastal counties, Save Our Shores' Executive Director Vicki Nichols says, "If you look at the economic contribution of California's coast, you clearly see the correlation between healthy resources and a healthy economy."

Nevertheless, mobilizing similarly broad ecosystem policies for grasslands, woodlands and even forests could prove more difficult, if not impossible. And so, taking into account population trends and developmental realities, should Californians anticipate a future in which virtually all parks, preserves and wilderness areas are elevated out of ecological context and engirded by various degrees of atonal suburbia?

"That's one future that people have to contemplate," says McLeod. "And if it's not something desirable, they've got to act soon to arrest the momentum in that direction."

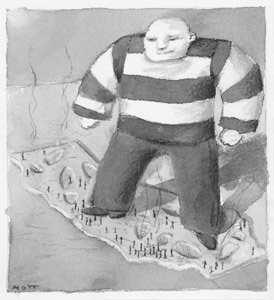

Like so many others, McLeod suggests that population trends are at the heart of California's resource management challenge. "The Department of Finance keeps the most precise numbers on population expectation, and they have held for a while that the population would double by 2040 to about 60 million. No matter how you cut it, that's a staggering number."

Is it possible for California effectively manage its natural resources--and its environment--well into a crowded future?

"I think it is," McLeod says. He pauses, then adds, "It has to be."

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Illustrations by Mott Jordan

From the October 24-30, 1996 issue of Metro Santa Cruz

Copyright © 1996 Metro Publishing, Inc.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)