home | metro santa cruz index | features | santa cruz | feature story

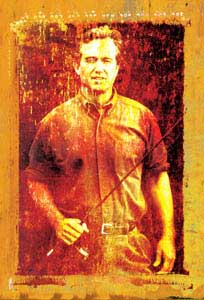

Fisherman's Blues: Kennedy found his way into environmental politics after being sentenced to community service with the Hudson River Foundation.

Resurrecting the Kennedy Mystique

Robert Jr. weds '60s idealism to 'me generation' economics to sell the environmental movement

By Mike Connor

The professional speaking engagement firm Keppler Associates Inc. represents Robert F. Kennedy Jr., but not necessarily because it agrees with his politics--it also represents Charlton Heston and Bob Dole. RFK Jr. is not even a particularly strong orator--while the content of his speeches is eloquent, passionate and sometimes even richly poetic, his voice is often clenched and quavery because of his spasmodic dysphonia, a disorder of the layrnx.

Still, Keppler represents him, probably for much the same reason it represents Ted Kennedy Jr., Kerry Kennedy and Kathleen Kennedy-Townsend--because they're all part of one of the most fascinating family dynasties in American history.

Not that RFK Jr. doesn't have an interesting past of his own. After the assassination of his father, Robert F. Kennedy, in 1968, RFK Jr. went on to earn a political science degree from Harvard and a Juris Doctor from the University of Virginia Law School.

In 1983, during the rise of the "Me" generation, the 29-year-old RFK Jr. was arrested for possession of heroin. His subsequent 800 community service hours were spent with the Hudson River Foundation, apparently a life-changing experience for the young lawyer. He was hired on as the group's chief prosecuting attorney in 1984.

Using the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1888, Kennedy and the Hudson "Riverkeepers" were able to secure a bounty for successfully reporting and prosecuting environmental polluters along the river. They used the money to buy a boat, which they named "The Riverkeeper," which continues to patrol the Hudson looking for polluters. He wrote a book about the Riverkeepers in 1997, and another one in 2004, about the Bush administration's treatment of environmental regulations, called Crimes Against Nature.

"Today," warns Kennedy in Crimes, "George W. Bush and his court are treating our country as a grab bag for the robber barons."

His hyperbole-filled romp through the Republican war on environmentalism has launched him to the forefront of the modern environmental movement. In his speeches, he often invokes Earth Day 1970 without even a hint of irony. Given the opportunity to leap instantly into the future, what countercultural idealists from the '60s who started the environmental movement would have recognized its silver-spooned, well-pedigreed and power-suit-wearing-lawyer heir making the rounds on the corporate lecture circuit?

UCSC Arts & Lectures placed an order for his "Our Environmental Destiny" speech, which he'll deliver at the Civic Auditorium on Jan. 26. It's one of three standard speeches he gives (the other two being "The Power of Law" and "Contract With Our Future"), all of which reconstitute the environmental ideals of 1960s counterculture into wonkish economic terms.

"The economy," says Kennedy in a favorite turn of phrase, "is wholly a subsidiary of the environment."

"Pollution," he declares, "is deficit spending."

And, "The best thing that could happen to the environment," asserts Kennedy in his best Milton Friedman impersonation, "is if we had a free market economy."

Gone are most of the airy-fairy pleas of his predecessors to save the trees and the whales. Even his appreciation of nature is decidedly hawkish. RFK Jr. is a Master Falconer who used to be president of the New York State Falconer's Association. In a surreal anecdote from "Our Environmental Destiny," he tells the story of a wilderness experience while visiting his uncle, JFK, at the White House.

"Since I was 11 years old," says Kennedy, "I always loved raptors. I could look up on the old post office building in Washington, D.C., and there was a pair of Eastman and Adams peregrines nesting up there, which are the most spectacular predatory bird that we have in this country.

"It was salmon-painted, a beautiful bird, with a white coverlet over its nare. It could fly over 200 miles an hour. It was the most beautiful subspecies of the peregrine falcon, and I could watch these birds come down Pennsylvania Avenue from top of the post office at those speeds and pick pigeons out of the air 40 feet above the heads of the pedestrians, and then fly back to the cupola of the post office. And to me, something like that was as exciting as visiting my uncle at the White House. But that's a site that my children will never see."

Despite his decidedly anti-dovelike appreciation of nature, RFK Jr. claims deep admiration for St. Francis of Assisi, about whom he wrote a children's book "because he understood the connection between spirituality and the environment," Kennedy told a young reporter from MyHero. "He understood the way God communicates to us most forcefully is through the fishes and the birds and the trees, and that it is a sin to destroy those things."

Kennedy is still the CPA for the Hudson Riverkeepers, is now president of the Waterkeeper Alliance and organizes collaborations between those organizations and students of the Pace School of Law's Environmental Litigation Clinic, who get to prosecute Hudson polluters as part of their coursework. He's also senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council and hosts a progressive radio show on Air America called Ring of Fire.

Metro Santa Cruz spoke with RFK Jr. on Dec. 22, while he was vacationing with his six kids in Jackson Hole, Wyo.

Metro Santa Cruz: You talk a lot about how small towns should shun polluting industries in favor of more sustainable industries. What sort of transition do you envision for them?

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.: Without a specific example, all I can do is answer that in generalizations, and what I would say is that in every case, in a hundred percent of situations, good environmental policy is identical to good economic policy. If you want to look at the long term, if you want to measure the economy, this is how we ought to be measuring it, based upon how it produces jobs over the long run, and how it preserves the value of the assets of our community.

Investing in the environment does not diminish the wealth of a community, it's an investment in infrastructure, the same as investing in telecommunications, road construction; it's an investment that every community has to make if we're going to ensure the economic vitality of our generation and the next generation.

Santa Cruz has actually invested in 'environmental infrastructure'--greenbelt lands--and has pretty strict policies about what sorts of industries can locate here. The problem now is that city leaders are having trouble finding a new economic engine that's environmentally responsible.

Well, I can't tell you, because I don't know enough about what's happening on the local level in Santa Cruz, but I can point out to you plenty of communities that have done the opposite and have lived to regret it.

Right now we have a federal government that basically has shifted the costs of running the United States onto the backs of local communities. There's not a community in this country that isn't making difficult economic decisions right now. But you know in the long run, the decision to invest in the environment is gonna end up bringing big paybacks to communities that decide to go that direction. I can point to many communities that have done that and are flourishing. And I can point you to many communities that have gone the opposite way, have huge burdens on their people--on future generations--many of them will never be able to recover from.

Do you have specific examples of any of the communities that are flourishing, that serve as positive models of what other communities seeking to move in a more sustainable direction might emulate?

I think the most used example is, you know, Portland, Ore., which has a greenbelt, and a lot of those protections have been dismantled, but Portland, by investing in the environment, it's always in the list of the top five most desirable cities in the United States to live, and, you know, property values have gone up.

Another example would be Nantucket, Mass., which has the strictest land control ordinances in the nation, and also some of the highest land values, as a result. The land values in Nantucket essentially quintupled after they put in zoning and building ordinances that are highly regulatory, that even regulate--you can't change your mailbox in Nantucket without going through the permit process. They're burdensome in the short term, but in the long term, everybody on that island has been enriched because of that investment in infrastructure, in the environmental infrastructure, because everybody knows that their neighbors can't screw up their community, and that assurance has a huge value.

In Florida, the same thing. There's places all over the country that have made these extraordinary investments in environmental infrastructure and they've reaped huge payoffs over the long term. That doesn't mean that they're immune from economic problems. The current economic policies of our federal government, which has shifted a lot of the federal burdens to the states and the local communities for education and pollution control, etc., those policies have created a, let's say, an environment where there's no local community that can afford to not have imaginative and hard-working, innovative leadership, because at this point the burden is so great on local communities to come up with money. That used to be a federal responsibility.

And apparently you've been working on the federal level on some guidelines to at least cut down on some environmental abuses while communities are coming up with creative ways to sustain themselves?

To deal with these new burdens that have been put on them, yes. What this administration has done is it's essentially engineered a huge shift in wealth away from local communities and from the middle class into the hands of large corporations and the wealthiest Americans, and so the burden now has increased dramatically on local communities to support their own education programs, their health programs and their environmental programs. Those burdens used to be much more of a federal responsibility. But the money that was coming in for that has been given back to the richest Americans and the corporations in the form of tax cuts, and it is not there for the local communities. The local communities are under terrible pressure, and what it means is that all of us on the local basis have to kind of have very imaginative leadership if we're going to keep our essential values intact.

Can you talk briefly about what you meant by, something to the effect that 'the best thing that could happen to the environment was if we had a truly free market economy?'

The free market encourages efficiency. And efficiency means the elimination of waste, and pollution is waste. And a free market also would encourage us to properly value natural resources, and it's the undervaluation of those resources that causes us to use them wastefully.

So, in a true free market you can't make yourself rich without making your neighbors rich and without enriching your community. But what polluters do is they make themselves rich by making everybody else poor, and they do that by escaping the discipline of the free market, by shifting their costs of doing business onto the backs of the public.

Can you give me a specific example?

You show me a polluter, I'll show you a subsidy, I'll show you a, you know, a fat cat that's using political clout to escape the discipline of the free market and force the public to pay its production costs. When somebody puts, when a coal burning power plant puts mercury in the air, which poisons our fish, you know, or when they put ozone and particulates which give asthma to our children, which cause a million asthma attacks a year, a hundred thousand lost workdays. Those impacts impose costs on the rest of us that should, in a true free market economy, be reflected in the price of that company's product when it makes it to the market.

But corporations are externalizing machines; they're constantly trying to figure out ways to get somebody else to pay their costs of production. And one of the ways of doing that is through pollution. Pollution is just a way of forcing the public to pay the cost of your profits [laughs].

So, what all the federal environmental laws were meant to do was restore true free market capitalism in America by forcing actors in the marketplace to pay the true costs of bringing their products to the market, rather than shifting those costs to the public.

Any recommendations for how people can get involved in the fight?

Join an environmental group. Not everybody can give their life to this battle--people have to feed their children and pay their mortgages, and they have other jobs, and what I would say for those people is join an environmental group and support the people that are on the front line doing this work. But, you know, for those people who have decided that they want to commit their lives to a higher purpose, I would encourage them to come to the barricades and fight for the environment, because there's no more important issue.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.