home | metro santa cruz index | the arts | books | review

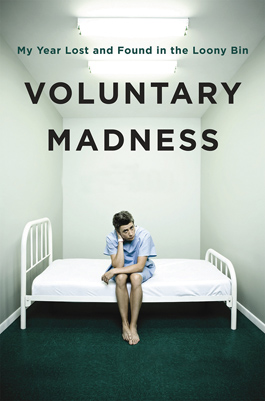

Accidental Tourist: Author Norah Vincent takes the measure of three mental health facilities in 'Voluntary Madness: My Year Lost and Found in the Loony Bin.'

Asylum Seeker

Author Norah Vincent takes on the mental health industry in a raw new memoir. She visits Bookshop Santa Cruz this week.

By Molly Zapp

Clearly the kid had problems," Norah Vincent observes in "Kid," a chapter in her new book about a fellow resident at a hellish mental health facility. None of the staff knew exactly what was causing Kid's mental health problems, or those that plagued Vincent or many other residents, but that didn't stop doctors from writing out prescription after prescription anyway.

An immersion journalist wielding a critical cultural lens, Vincent ponders the "why" behind mental illness that the facility staff neglect to address: "[W]hat might be causing those problems? Brain malfunction, acquired or inherited, recreational drug abuse, unstable or violent home and neighborhood life, or just plain time-of-life maladjustment and bad manners? It was anybody's guess. And that, of course, is exactly what his diagnosis is, a guess. A whole tangle of dysfunction and undesirable behavior blamed on his brain, on the behavior of neurotransmitters whose functions we cannot in any meaningful sense of the term measure, do not understand, and cannot regulate with any reliability or accuracy."

The bestselling author of Self-Made Man, an account of her experiences living incognito as a man for 18 months, Norah Vincent takes on the mental health treatment system in Voluntary Madness: My Year Lost and Found in the Loony Bin (Viking; 304 pages; $25.95 hardback). But this time, she isn't "passing": Vincent's own long-term struggle with depression and self-destructive behavior, her roller-coaster ride with prescription antidepressants and therapy and even some of the childhood abuse and trauma that led to her depression are all laid bare in raw detail. Though the book is far from a spill-it-all memoir, Vincent makes intimate parts of herself available to be dissected, analyzed and judged--first by herself; then by her doctors, therapists and fellow facility residents and finally by the reader. Revealing that much, she says in a phone interview from her home in New York, was no easy choice.

"I had a tremendous crisis of confidence, of whether I should keep in more of the raw things--just in overcoming the shame of speaking about very intimate things," Vincent says. "In the end, I decided that they were there to help other people, and I wanted to show what happens in therapy in real time, what goes on beyond closed doors."

In the book Vincent divides her time between three distinct "loony bins" specifically chosen for their variety (and identified by pseudonym). She begins at Meriwether, an impersonal urban facility where individual freedom and therapy are scant and psychotropic drugs are doled out like cupcakes at a toddler's birthday party. When her psychiatrist tries to persuade her to take Lamictal, a mood stabilizer she'd abandoned years before because it caused swelling in her groin, she asks, "What neurotransmitter does that work on?" The doctor didn't know, but wanted her to take the drug anyway. Her therapy was a slim 10 to 15 minutes per day.

Next is St. Luke's. Before arriving at the Midwestern sanatorium, she decides to go completely off Prozac, in part to induce another episode of full-blown depression. ("I know, I know. Stupid," she writes.) At St. Luke's, she finds a doctor who respects her as a human being: she is allowed to have a say in what type of medication she takes, is allowed more freedom of movement and respect from staff and has longer and more intensive therapy.

Her final and most healing stop is at Mobius, a center in the South that emphasizes comprehensive treatment and process therapy and views drugs as just one option. The entire approach embodies "a shift from the disease model to the wellness model," Vincent writes. Mobius is where she most directly confronts and examines her past trauma and her subsequent depression and self-destructive behaviors. After 200 pages of her skimming over What Happened, the honesty relayed in her "really ugly stuff" makes it the strongest part of the book.

'You Don't Have to Do It'

Vincent describes her journalistic approach as one that looks at "the intersection of the individual and society." Though she uses her individual experiences to form a critique of the mental health industry as a whole, Voluntary Madness does not purport to be a comprehensive examination of the system: ultimately, this book is about her. Nevertheless, Vincent heavily criticizes the shady pharmaceutical companies, with their inconclusive data, prescription-pushing and doctor-schmoozing, but only in general terms; though not exactly new or shocking, her assertions would have be strengthened if she had included citations or a brief bibliography, simple notations that she omits.

Doc Vincent concludes Voluntary Madness with her own prescription for wellness, one that requires people to be active participants in their own mental health and pursuit of happiness.

"You don't have to rely on the institution to do this for you, you don't have to rely on a doctor," she says. "I'm not saying never see a doctor, never take meds, but you don't have to do it within an institution. You don't have to rely on a doctor's prescription, or rely on this one method, this one way of seeing it. There are other approaches, including psychotherapy, friends and family, fellow sufferers."

And, apparently, writing a book. Voluntary Madness relays Vincent's emotional evolution and the shift she experiences when she transforms from journalistic observer to actual, real-life human with flaws and emotions and anger--someone who is on the continuous journey of healing. Vincent seems to regard the surprise pain and self-discovery as an occupational hazard.

"I think that's part of the nature of immersion journalism," she says. "You're knee-deep in the mud before you realize it, and you didn't intend to get so dirty."

NORAH VINCENT discusses 'Voluntary Madness: My Year Lost and Found in the Loony Bin' on Friday, Jan. 16, at 7:30pm at Bookshop Santa Cruz, 1520 Pacific Ave., Santa Cruz; Free. 831.423.0900.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|