home | metro santa cruz index | news | santa cruz | news article

Photograph by Lewis Watts

Katrina Revisited: The View from Here

In the wake of the flood, a local gathering of academics sorts through questions of class, race, politics and place

By Bill Forman

In 1977, Black Panther co-founder Huey Newton found reason to reach out to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The case of Alan Bakke, a white student suing the University of California over its racial quota system, was making its way to the Supreme Court, and the fate of affirmative action was believed to hang in the balance. In a candid letter to NAACP counsel Nathaniel Colley, Newton insisted it was time for the NAACP to "stop playing its game of saccharine sensitivity and let our people go to school," a goal that must be achieved, he added, "by any means necessary."

A decade earlier, that last phrase alone would have helped secure addition funding for the FBI's COINTELPRO operation. But in this case, Newton wasn't talking about taking to the streets. Instead, the famed militant was proposing a strategy that, in retrospect, was both more pragmatic and more politically astute than the one adopted by the traditionally more mainstream NAACP. Let Bakke in, Newton reasoned, and let go of the embattled racial quota system; replace it instead with an equivalent mechanism based on economic need: "With the removal of one concept, the race concept, from the program's language, we will have our program. It will still be dominated by blacks. Who else," Newton reasoned, "is more economically and educationally disenfranchised?"

Huey Newton's advice apparently fell on deaf ears, as the NAACP continued to throw its weight behind a quota system that the Supreme Court would soon rule against. (Of course, with characteristic ambiguity, the court opted to uphold the concept of affirmative action even as it struck down the quota system which, however flawed, had served to translate rhetoric into action.)

Nor, for that matter, was Newton's overture to the NAACP mentioned during a daylong Katrina conference held Jan. 21 at UCSC's Oakes College. But the fundamental dilemma he was tangling with--the age-old pitting of race against class--was very much in evidence throughout the day.

If anything, the stakes simply appear higher today, with Hurricane Katrina rescue and recovery efforts so thoroughly botched that critics like Mike Davis have likened them to "ethnic cleansing." Davis was, in fact, the scheduled keynote speaker, but it was announced at the conference's opening session that the activist author had to cancel his engagement after contracting pneumonia during a trip to New Orleans. That left comparatively mild-mannered Canadian professor Robb Shields with the unenviable task of firing up 100 or so weary academics on a rainy Saturday morning.

In keeping with the conference's title--Reflections on Katrina: Place, Persistence & the Lives of Cities--the University of Alberta professor started out with an anecdote about Henri Lefebvre's first visit to Santa Cruz. (Trust me, it's not worth retelling.) He then wondered how Lefebvre's theory of displacement might contribute to our understanding of the disaster. To the best of my knowledge, neither Shields nor anyone else ever got around to answering that. Instead, it was Shields' contention that Katrina should also be seen through the lens of class analysis--a view he admitted had long since been relegated to aging white Marxists--that sparked immediate interest and debate.

Race to the Bottom

"You raise the issue of class," said CSU Sacramento professor Stan Oden, "but the tragedy of New Orleans has such a strong racial aspect to it in a way that--I don't want to say that it trumps class. ..."

Failing to find a less divisive word, Oden went on to explain how, just watching his television in California, he knew that the levee had been breached before the communities that were hardest hit by it knew. He wonders if white communities had somehow been given advance warning while black communities had not.

Donna Hall is a former teacher and current doctoral student who has lived in the Deep South and whose husband, visiting professor Phil Steinberg, organized the conference. She offered up her own observation about how race and class figure into what she sees as a geographic "pecking order as to what neighborhoods are located in the flood plains."

"In Tallahassee, Fla., the poorest black people live in the areas that flood regularly, and the next area is the poor white people and the college students," explained Hall, getting a laugh from the students in attendance. "And they get flooded a little less regularly. And then we [Hall and her husband] are in a nice middle class neighborhood that's elevated, so we get some damage but no real flooding. And then the really white, more well-off people live out in this one sector of town that is really segregated from all the rest of us people." Hall wonders what's to stop New Orleans from repeating segregation patterns during the rebuilding process.

"One thing I think we really need to try to avoid is discussions about "It's really race" or "It's really class," suggested Jim Clifford. A professor in UCSC's History of Consciousness program, he cautioned against the articulation of class and race as "essentialist" categories that serve to diminish the other.

"What's so incredible," continued Clifford, "about the New Orleans case is: You know how social scientists talk about social stratification as a metaphor? In New Orleans, the metaphor is utterly literal. Exactly how low you are physically, exactly how high you are physically, can be mapped right onto money. And yet, if it's just about money, then why is it that folks on the lower end tend to be African American? All of this has to be part of our analysis, but we need to avoid this zero sum game that says it's either this or that."

It's hard to remember a time when the competition for the distinction of which group is most victimized by the current political climate seemed so plentiful, despite the fact that the victor who wins such a title gets the least in the way of spoils. Thankfully, there are pundits like Rush Limbaugh around to help explain it all.

Clifford cited a recent Limbaugh broadcast in which even the right-wing commentator was motivated to weigh in on the class vs. race issue. Never one to resist blaming the victim, the unofficial Oxycontin spokesman apparently insisted that all those folks on their rooftops waiting for helicopters to show up and rescue them really needed to learn just one simple lesson: Stay in school.

Fables of the Reconstruction

Unlike Limbaugh and his belated education advice, Louisiana's governor offered more immediate solutions as the hurricane approached. "I was in New Orleans when Katrina hit the city," recalled Jordan Flaherty, a New Orleans SEIU organizer and editor for the magazine Left Turn. "In the days leading up to it, our governor advised us to try to pray the hurricane down to a Level 2."

Flaherty explained that, while New Orleans is a very prayerful city, they weren't quite able to pray the hurricane down enough. "A lot of us tried to pray it east a little bit," he added. "I want to apologize to the people of Mississippi for that. I think we were a little bit successful, but we didn't quite pray hard enough."

Of all the day's speakers, Flaherty was clearly the closest to the absent Davis in his condemnations of the government's actions and intentions. Condemning what he alternately calls the "disaster industrial complex" and the "reconstruction cabal," the energetic union organizer spoke of how the New Orleans teachers union has been reduced from 7,000 members to 61, as virtually all public schools are replaced by charter schools (pushing the city toward the front of the national trend to do away with public education entirely).

Flaherty also questioned the motivation behind the conventional wisdom that only half of New Orleans' evacuated residents will ever return: "Where does this statistic come from? What they're doing is keeping people out and then predicting that those people won't be back."

By contrast, Flaherty suggested, the city was welcoming students back with open arms. Yet its poorest residents are clearly being caught in a Catch-22 situation.

"People from New Orleans want to come back but they're being stopped from coming back even to this day, and the Mayor's Commission is part of that," said Flaherty, who claims the commission includes prominent members of Momus and Comus, former all-white Mardi Gras crews who dropped out when the event became integrated to host segregated private balls. "This whole idea that, you know, you can come back and start rebuilding your neighborhood, but if in four months we decide not enough people from your neighborhood have started rebuilding, then we're gonna demolish it. I mean, nobody is gonna be coming back under those conditions."

Flaherty likens New Orleans today to a battleground. "Halliburton is ready, Blackwater is ready and we need to be ready," he insisted, urging listeners to support groups like Common Ground, a New Orleans collective set up by, as luck would have it, a former Black Panther.

Photograph by Lewis Watts

Domino Theory: Reports of New Orleans music legend Fats Domino's death in the flood were, as it turns out, thankfully exaggerated. The above photo of his house shows a mourner's graffiti as well as the FEMA markings that are ubiquitous throughout the city.

An Onerous Cost

While conference participants ultimately found more areas of agreement than conflict, one fundamental area of disagreement arose between Flaherty and Louisiana State University professor Craig Collen.

"I've been been a strong advocate from day one," said Collen, "of delimiting certain areas of the city, regardless of class, regardless of color, and saying that, based on flood risks, we will transfer those areas into a flood retention basin."

Collen likened his strategy to the government's response to the flood of 1927, in which the levees were intentionally broken further up the river. As a result, New Orleans itself was spared and, Collen argued, even the displaced population of poor farmers further up the Mississippi--who were essentially sacrificed to save the city--eventually recovered.

Collen figures that by restoring coastal wetlands, removing certain areas from residential use and helping relocate the displaced communities, New Orleans can be protected from future disasters without posing "an onerous cost on the American public at large."

Whether or not such proposals shift a far more onerous cost onto an already devastated population is a subject that can be debated. Yet such alternatives may be the only alternative when the current president, despite his reassurances that New Orleans is one heckuva place to bring the family, is steadfastly refusing to allocate the funds that would protect it from another Katrina, much less a possible Level 5 hurricane.

But Flaherty resisted the idea that people simply shouldn't live in certain areas of New Orleans. "You can look anywhere and find examples of places where people shouldn't live there," he countered. "Florida has hurricane after hurricane after hurricane and people still live there. Las Vegas is located in the desert and is not sustainable, while Los Angeles has fault lines. There are people on the coastline who build their houses on cliffs. All these places, you can find reasons to say nobody should live there. I think it's crazy to live up North where its so cold and freezing! There's all kind of reasons why people shouldn't live in a place. But the people of New Orleans are not living in an unsustainable area."

New Orleans deserves to be saved, Flaherty argued, and it's up to the rest of us to see that it happens. "It's a place with so much of a sense of community, which has given the world jazz and R&B and hip-hop, besides serving as a major port," he mused. "New Orleans has brought so much to the United States culturally and financially, and yet the people of New Orleans have gotten so little back."

Photograph by Lewis Watts

Please don't shoot the photographer

The photos in this story were all taken by Lewis Watts, a professor of art at UCSC who went into New Orleans as an "embedded" photographer. "This picture of me is with the National Guard in the 9th ward, which in mid-October was the only way I could get into the neighborhood," he explains.

Watts also just completed a new book Harlem of the West, The San Francisco Fillmore Jazz Era, co-written with Elizabeth Pepin, featuring photographs and oral histories about the community that sprung up in between the 1940s and 1960s around the migration of Southern African Americans who came west to work in the shipyards.

An exhibit of images from the book will run from Feb. 8 through June at the San Francisco Performing Art Library and Museum, with an opening concert featuring the Fillmore Preservation Big Band led by UCSC Professor Karlton Hester on Feb. 7. For more information, visit www.sfpalm.org/exhibits/Harlem/Harlem.htm.

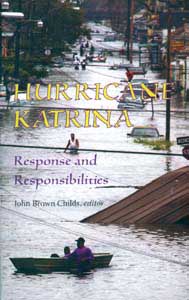

UCSC Prof and Literary Guillotine owner publish Katrina benefit book

The idea, according to editor John Brown Childs, was to "help fill the space between the immediate journalism that emerged during the Katrina catastrophe and the more detailed writing that will undoubtedly appear in the next year or two."

To that end, Childs gathered up essays from colleagues at UCSC and throughout the country, and the result is Hurricane Katrina: Responses and Responsibilities. The book's 31 essays were all donated by their authors, who include musician Wynton Marsalis, Tikkun editor Rabbi Michael Lerner, Detroit activist Grace Lee Boggs and academics Paul Ortiz and Stan Oden (both of whom were at UCSC's Reflections of Katrina Conference).

The book was published by Literary Guillotine proprietor David Watson's not-for-profit New Pacific Press and retails for $10, with proceeds going to the People's Hurricane Relief Fund.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.