home | metro santa cruz index | the arts | books | review

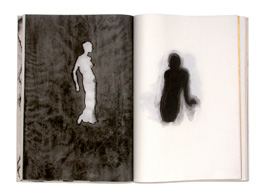

Johannes Strugalla & Francoise Despalles, 'forma,' 2006, Ultrachrome print on Japanese paper, 12 inches x 8.25 inches

ATYPICAL: The Sesnon Gallery's exploration of the book as medium goes well beyond typeface.

Not by the Book

What if books contained no words, just ideas?

By Maureen Davidson

WITHIN the next two decades, books as we know them will likely become curiosities, artifacts of an old way of life. Paper books, which set forth ideas in a linear manner, have already given way to the omni-directional, multimedia Internet as a means to reach and teach the rewired human brain in the digital age: goodbye, printed newspapers and textbooks; hello, "Please enter your library card number to download Fahrenheit 451."

Not so fast there, Fireman! Communication of textual content is not a book's only raison d'Ítre. Books have a sensual quality—not just in their words or images, but in the feel of the paper, the design of the page, the physicality of a fat paperback perched on one's ribs. Many humans have life relationships with specific books.

Artists have made books exquisite since the earliest manuscripts, but in the late 20th century the form and the idea of The Book began to be used by artists not just to contain art but to be art. The current exhibition at the UCSC Sesnon Gallery, "Book as Medium: Holding/Withholding Text," closing this week, is a fascinating exploration of the book as conceived by 28 international book artists. The exhibition is co-curated by Sesnon director Shelby Graham and book artist Felicia Rice, a current Rydell Award recipient whose own book art can be seen at the Museum of Art and History.

The Sesnon show traces the lineage of artist books to two traditions: those who use traditional bookmaking techniques (printing, binding, typography) to produce a work organized sequentially and those who deploy the "idea" of a book more conceptually in a tradition that can be traced back to the Fluxus movement of the 1960s.

An especially meaningful example of the traditional lineage is the large-format, hand-printed, limited (129) edition The High Sierra of California (2000) by Tom Killion at his Quail Press (then located in Santa Cruz), with text by poet Gary Snyder. Killion took three years to produce this exquisite 15-by-19-inch Japanese-stitched book with many full-sheet color woodblock prints on handmade Japanese paper. The text is hand-set letterpress type, gracefully integrated with Killion's illustrations. The result is a deeply reverent immersion in vivid nature—you can almost hear it hum.

A conceptual edge shows within the traditional lineage in Despatches (2008). Printed by Foolscap Press' Peggy Gotthold and Lawrence Van Velzer in an edition of 185, the Despatches are three slender 24-page travel journals written by Michael Katakis. The typeset journals contain maps in their center spreads and small, hand-mounted photographs. The books fit into a papyrus "dispatch case" that seems as if it might be an artifact of a historic desert campaign. The form becomes a metaphor for the content, melding the traditional with the conceptual approach.

Artist/librarian Jody Alexander embraces and emphasizes the notion of the book as artifact. Her love of printed books drives her to interact with them, like one of those people who compulsively underline words or passages that have special meaning. In her Felix Notebooks, a shelfful of books printed in weighty Gothic type have had their covers removed to reveal the fragile spines and pages. With a substantial red thread, Alexander has stitched through the words in the book, stitched pages together, stitched decorative and sturdy spines. Each book bristles with celebratory red threads—threads of meaning, full of good news, felicitous thoughts, all made sturdy or perhaps ready for ritual immolation.

Below the Notebooks, another shelf holds books stitched into protective coverings of felt or batting. The artist may be making an ironic allusion to the Fluxus movement's Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), who created an elaborate backstory for himself in which being wrapped in felt figured memorably. Or Alexander may simply be showing that these books are fragile and precious and in need of protection. Artwork about ideas—so satisfying!

At another point in the continuum, Victoria May shows a work that is a book in concept, because it unfolds ideas in a sequential manner, but its form is within 17 rectangular wooden frames hinged together, each frame strung with horizontal threads, looking like a music staff. One of the frames of Primavera (1999) holds flies impaled by the threads—could they be read as a staccato passage of music? Seeds suggest the same within another frame; small photographs, a potato bug, a tooth, are threaded within other frames to become a sequence that aches to be decoded.

This exhibition is worth spending time with, for white-gloved turning of delicate pages, for contemplation of meaning of this library of ideas.

BOOK AS MEDIUM: HOLDING/WITHHOLDING TEXT continues at the Sesnon Gallery, Porter College, UCSC through Saturday, March 6. Demonstrations, discussions and closing reception on Friday, March 5, 2–6:30pm. 831.459.3606 for information or arts.ucsc.edu/sesnon.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|