home | metro santa cruz index | features | santa cruz | feature story

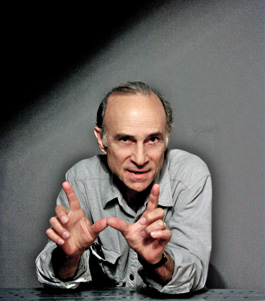

NOVEL EXPERIENCE: Best known as a poet, essayist, translator and newspaper publisher, Santa Cruz–based writer Stephen Kessler now adds 'novelist' to his vitae.

Sex, Drugs & Psychosis

In a heavily autobiographical first novel set partly in late-1960s Santa Cruz, Stephen Kessler explores the excesses of an era

By Maureen Davidson

"What is this?" I asked him. Almost whispering. "Where are we?"

"Hall of Justice. City Prison. What are you in for?"

"I don't know. Are you sure this isn't staged? Are you a poet?"

"Huh? Staged?" He looked at me as if to ask, What are you on? Then he reflected for a few seconds. "Yea, well, I write songs sometimes."

from The Mental Traveler by Stephen Kessler

THE PHOTOGRAPH on the cover of The Mental Traveler is an extreme close-up of a young white man of indeterminate age, thick black beard and moustache bristly and unkempt, forehead knotted, head bowed toward the camera. He appears consumed by his thoughts, overcome by deep emotion, his forehead ready to burst.

So we have an immediate physical impression of Stephen K., the protagonist in an extraordinary first novel by much published and awarded poet, translator, journalist, essayist and sometime Santa Cruz Weekly contributor Stephen Kessler, who lives in Santa Cruz and the North Coast hamlet of Gualala. The cover photograph is, in fact, a portrait of Kessler as a young man. The Mental Traveler (Greenhouse Review Press, $18 paperback), Kessler insists, is not. "I wrote it as fiction because I believed I could tell a truer story that way," he says. The disclaimer on the imprint page bears out the message: "Any resemblance to actual persons, etc."

But that's one level at which this novel fascinates; references to people and places, from Santa Cruz to San Francisco to Los Angeles, are as thinly disguised as the hero's identity. As the story begins, we find Stephen K., a graduate student in literature at the newly opened UC–Santa Cruz, living in San Lorenzo Valley's Love Creek Lodge. He's hiding out—from a failed marriage, from the pressures of his intellectual ambition vs. the bureaucracy of graduate school and from the explosive living reality of 1969, the year of Nixon's inauguration, My Lai, the draft lottery, the Alcatraz occupation, the Manson murders and Woodstock.

In a few pages Kessler immerses the reader in the era, the earnest camaraderie of students and freaks, the plentiful fat reefers, the ever-ready psychedelics, the love so "free" Stephen finds it oppressive, the discussions spiked with conspiracy theories. Meanwhile our hero commutes to UCSC along Highway 9 in a modified Volkswagen bus.

Kessler draws the readers into the momentum of the lives of the central characters from the singular point of view of Stephen, who experiences the story and provides the narration. As his protagonist moves through the population at large of professors, fellow students and fellow travelers in that tectonic shift of an era, Kessler draws a large cast of characters through apt, naturalistic dialogue that nails the stoney courtliness and inanities of the freak world, stipples the canvas with the sharp bite of obsessive conspiracy theorists, then fills the rest of the senses with Aretha, the Doors and the smell of pot and wood smoke. So in 1969 in Santa Cruz, a conflicted young man struggles to find his way as a poet while maneuvering the currents of respectable academia. Then he takes off to hear the Rolling Stones at Altamont.

Along with approximately 250,000 people on every kind of drug imaginable, our protagonist has an epiphany at Altamont Speedway to the soundtrack of the Jefferson Airplane, Santana and the Stones. He isn't alone in this. As one character puts it, "I feel like my psyche's just been rinsed out with a fire hose." A chorus of other characters agree: Altamont has been a watershed moment for the rock & roll nation. It definitely has been for Stephen K.

From this early chapter, the rhythm of Kessler's writing changes as we follow the protagonist from his lysergic experience into deepening psychosis that takes him to San Francisco on a search for a trusted teacher who will surely tell him what to do. His quest takes an abrupt turn to the San Francisco City Jail, the psych ward of San Francisco General Hospital and from there to institutions public and private in Northern and Southern California as Stephen watches and listens for instructions about his poet's role in bringing about "new harmonious social order." He seeks out messages encoded in headlines, spelled out in plumbing pipes, delivered by Black Panthers disguised as hospital orderlies and brought to him by the police who, if he gets it right, will publish his collected poetry after he graduates from the City Jail—which must, after all, be the depths of poetry hell.

As Stephen's obsessions increasingly consume him, the reader is drenched in the cataclysms of maniacal internal and spoken rantings bejeweled with exquisite observations and beautiful ironies. A page-long sentence reads like an extended jazz improvisation so far outside it spins a few months out of sight but never out of mind, its long strange passages poetic and terrible enough that you don't care they have moved far away from any apparent thread of reason. The dis-chords are played by the maestro on an instrument as ancient as history. The voice becomes a voice in your own head, mesmerizing, licking your temples, drawing you into the words, carried by words into unfamiliar and dangerous ideas. The music it creates is heartbreakingly funny and gloriously cruel, with just enough glimmers of crazy wisdom to make you hold on, gasping, and just in time bring you back to the arc of the story.

In The Mental Traveler Kessler writes an archetypal hero's journey in the tradition of Don Quixote, God's valiant but deluded knight, who defied the authority of church and state as he traveled on his self-proclaimed holy quest to save the world. It's also a "road" novel whose character, along with Twain's Huckleberry Finn and Kerouac's Dean Moriarty, travels America in search of his own identity. Stephen's quest satisfyingly delivers the reader to the back of the book, where a second portrait of Kessler today smiles beatifically above the Author's Biography. In the biography, the author reveals that an "acute psychotic episode in 1970" led him to abandon his academic career to pursue writing full-time.

When we met, Kessler dug into his ubiquitous book bag to bring out copies of "last year's book," Luis Cernuda: Desolation of the Chimera, which has just been announced as a finalist for the 2010 Northern California Book Award in translation, and two translations of Jorge Luis Borges published by prestigious Penguin Classics: the Poems of the Night, with many of Kessler's translations, and the just-released The Sonnets, which Kessler was honored to edit.

The books on the table are only the most recent evidence of Kessler's prodigious muse, proof indeed that the quest from tortured young man on the front cover of The Mental Traveler to accomplished author on the back was one wisely undertaken.

STEPHEN KESSLER reads from 'The Mental Traveler' on Thursday, March 18 at 7:30pm at Capitola Book Café, 1475 41st Ave., Capitola. Alta Ifland also reads, from 'Elegy for a Fabulous World.' (831.462.4415 or www.capitolabookcafe.com)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|