home | metro santa cruz index | news | santa cruz | news article

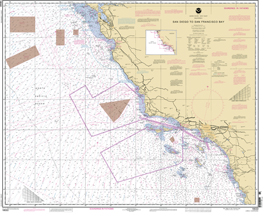

Map courtesy MBARI

No-Go Zones: The shaded boxes indicate general areas where chemical weapons stocks were dumped after World War II.

Map Quest

A scientist from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute calls for more study of sites off the Central Coast where tons of chemical weapons were dumped.

By Steve Hahn

Chucking a plastic bottle out the car window during a beachfront drive might seem like a minor infraction after learning what military officials from around the world have dumped into the oceans. For two decades after World War II, massive stockpiles of chemical weapons, hoarded but largely unused by military leaders, were thrown over the side of warships to accumulate on the ocean floor. These chemical dump sites exist all over the world, from Australia to Italy. A recent report from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) reveals that seven such sites are located off the California coast, including two found a little over 100 miles to the northwest of Monterey Bay.

MBARI chemist Peter Brewer believes it's time to revisit these sites and determine where, exactly, the nasty chemicals really lie. It's an unfortunate fact that details regarding the dumping activities were not well recorded. Brewer brought attention to this problem in his article, "What Lies Beneath: A Plea for Complete Information," recently published in Environmental Science and Technology. Brewer didn't take the dangerous journey out to these dump sites himself, but he did gather all the best information available on them.

What he found was enough to give any good citizen of Planet Earth the shivers. When the U.S. military decided the ocean floor would make a good dumpster back in 1946, it didn't get too specific about which nerve agent was dumped onto which marine habitat. Instead, these masters of war, who were almost completely unsupervised at the time, simply drew up vague boxes on a map, jetted out to these general areas on Navy ships and start launching the sealed canisters of mustard gas, sarin and other deadly chemicals off the side. As long as the canisters landed somewhere within the imaginary lines of the box, the military figured it had done its job.

Brewer doesn't advocate cleaning up these sites--that would be next to impossible--but he does believe that making these boxes on the map more accurate would be wise as scientists and others probe the deep sea more and more often.

"If you have a box that is 50 miles by 20 miles, you'd hope that the actual [dump] site might be in the middle of the box, therefore providing a safe radius around it," explains Brewer. "In reality, the weapons could be in one corner of the box. So you might have a one-mile warning in one direction and a 30-mile warning in the other direction. None of this makes any logical sense. I think it should be explored further, especially as we're laying more cables across the ocean and deep-sea exploration is increasing."

Little is known about the dump sites located off the California coast, but some details have become available over the years. Brewer reports that lying on the ocean floor just 55 statute miles west of San Francisco are 1,257 tons of lewisite, a chemical agent invented by the United States during World War I that causes rashes, swelling and blistering. There were also 301,000 mustard gas canisters dropped in the same area. The chemical contents of the other two dump sites off the San Francisco coast are unknown.

Brewer is careful not to point fingers or exaggerate the situation. "There is no cause for public alarm or panic. From a technical point of view, the effect would be very restricted if these chemicals were to leak," he says. "The leak would be confined to a very narrow halo."

Yet Brewer also warns against the idea proposed by some that the U.N.-sponsored effort to eliminate all chemical weapons from military stockpiles within the next decade will wipe this nasty scar from human history for good. After all, these underwater canisters will eventually corrode, and then nothing will prevent the chemicals from leaking.

"It would be a shame to have a 'Mission Accomplished' party and say we've taken care of this problem, while we've left the other side of the equation untouched," warns Brewer.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|