home | metro santa cruz index | features | santa cruz | feature story

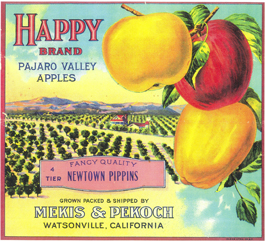

Photograph from Mekis Family Collection

Appletown Chronicles

A new book reveals the untold story of how Watsonville's Croatian immigrants transformed the apple industry and changed the Pajaro Valley forever.

By Donna Mekis and Kathryn Mekis Miller, with Introduction by Traci Hukill

Their names pepper the Santa Cruz County phone book--Bustichi, Franich, Gizdich, Scurich--but until now their history has remained hidden from plain sight. The Croatians of the Pajaro Valley changed the apple business for all time and left an indelible stamp on the Central Coast, but they didn't think themselves exotic enough to warrant a history of their own. In fact, if it hadn't been for two decades of pestering by historian Sandy Lydon, there probably still wouldn't be one.

As Donna Mekis tells it, her first inkling that the Croatians' story might be worth telling came when she was a student of Lydon's at Cabrillo College and wrote a paper about her extended family in Watsonville for a class assignment. Lydon read it and immediately suggested she consider writing more about the Croatians, whose history he'd decided would need to be told by an insider. Yeah, whatever, she thought. But after her marriage to poet Morton Marcus in 1986, she started running into Lydon more regularly, and he continued his good-natured badgering until finally, at one fateful dinner party in August 2003, George Ow offered to publish the thing, her sister offered to help write it and her husband offered to edit it. "How do you say no to that?" she asks.

Donna Mekis and Kathryn Mekis Miller dove in. They studied Serbo-Croatian with a tutor from the Monterey Institute of International Studies. They thumbed through stacks of newspapers, interviewed elderly acquaintances and traveled to the region on the Adriatic where most of Watsonville's Croatian immigrants had set sail in the last quarter of the 19th century. As the sisters worked, two salient stories began to emerge.

The first was the story of Dubrovnik, the medieval walled city that defined the region of Konavle, ancestral home to the Mekis, Alaga, Balich, Resetar, Bucich and countless other Watsonville families. Dubrovnik, Roman Catholic from time immemorial, occupied a privileged position in the medieval world. Singled out by Pope Gregory IX as the sole port authorized to do business with the Ottomans, it became a wealthy and cosmopolitan trading center with startlingly progressive laws--it had single-payer health care and laws governing the privacy of unwed mothers, among other things--and a populace to whom international trade was second nature. From the countryside, where families lived in complex groupings called zajednica, Dubrovnik drew second, third and fourth sons who could not inherit land and turned to business and seafaring. These were the ancestors of the people who sailed to California and eventually made their way to Watsonville in the 1870s.

"They're building ships, supplying ships, seeing people come in from Africa, Istanbul, London, France," says Mekis. "To them, the international world is a daily thing."

The second story was the tale of Croatian dominance of the Pajaro Valley apple industry. A chance outbreak of a pest called red scale left Santa Clara apple orchards incapacitated even as demand for apples in a rapidly growing San Francisco soared. Building on this piece of fortune and the innate sense of organization engendered by the zajednica, Croatian businessmen began offering "blossom contracts" to Pajaro Valley apple farmers--in essence promising to buy everything they grew--while simultaneously securing distributors who would get the apples to corner markets. Soon they were running packinghouses as well. It was vertical integration, and the sons and daughters of Dubrovnik saw possibilities in markets beyond California. In the 1880s they started shipping apples back East--the first perishable food item to be transported en masse--in a giant leap for industrial agriculture. "Nobody had ever sold perishable items farther than a wagon ride away," says Mekis Miller.

Blossoms Into Gold, the product of the sisters' long research, tells these stories and many, many more, shedding light on a long-overlooked part of local history. But both authors say they hope it will go even further.

"Sometimes people think poorly of or are resentful of people in the fields, but you realize everybody had their turn in the fields," says Mekis Miller.

"One of the things we've said is we want this to be a bridge," Mekis chimes in. "The more every group understands about the other people they are living with, the better we can break down barriers. The more people understand the different waves of immigration that came into Watsonville, the better off we'll be."

From Chapter 6, 'Croatian Life and Culture in Watsonville,' in Blossoms Into Gold, by Donna F. Mekis and Kathryn Mekis Miller (Capitola Book Company, 309 pages, $29.95)

The Croatian community in Watsonville grew around the apple packing sheds. It encompassed the area bounded by Walker and Rodriguez and Ford and First Streets ... By 1910 there were fifty-three fruit packing businesses in Watsonville, owned primarily by Croatian immigrants. Most were built along the railroad line on or near Walker Street. This is where the majority of Watsonville's Croatians lived and worked, and it was the epicenter of the town's Croatian Colony.

At first the immigrants were men, but it was not long before the men began looking to the old country for wives to bring to the Pajaro Valley. Some, like George Strazicich, went back to Croatia to find a wife. Others wrote home to their mothers and asked them to make the selection. "In the old days, some men wrote home to Croatia to ask their mothers to find them a wife. Some would pass pictures around and an agreement would be made by both the man and the woman." Then the Croatian man in America would pay for the young woman's passage.

In the period between 1890 and 1919, there were 109 Croatian weddings recorded at Saint Patrick's church in Watsonville. During this same period, there were 359 christenings of Croatian children. So, by 1900, there were already a number of established Croatian families living in Watsonville. In the early years a few Croatian men married non-Croatian women. But between 1907 and 1922 the practice was even less likely because during these years women who were U.S. citizens were actually required to give up their citizenship if they chose to marry a non-citizen.

For those working in the apple industry in the early days, the work was long and hard. Andrew Mekis remembered a typical day in the 1920s: "Everyone was up very early, maybe five a.m. My father would do some hoeing in our back yard for an hour or so before he went to work at seven a.m. My mother would be up at five a.m. too. They let us kids sleep until we had to get up for school." Andy's younger brother, Nick, added, "My father would go to work pruning and spraying the apple trees. At that time, mustard plants grew tall underneath the apple trees and the yellow foliage would be wet with fog or rain in the mornings. As a result, the pants legs of the orchardists' trousers would be soaked, and they would remain wet all day. Many of the men developed arthritis in their knees and ankles early on from working in these conditions." The men would also come home from work covered with yellow dust--the toxic pesticides they were using to spray the trees.

The jobs in the packing sheds were no easier. Women did most of the sorting. The sheds were not heated and the work was monotonous and unending. The women would heat bricks in their ovens at home and take them to work in the mornings. They would then stand on the bricks for warmth while they worked. After a long workday, dinner was normally served at six p.m.; and from seven thirty to nine in the evenings, neighbors would often drop by, or one family would visit another family.

Between 1905 and 1924, the population of Watsonville's Croatian colony grew. Poor Croatian immigrants continued to arrive by the hundreds in search of work and a new life, while the more fortunate ones solidified their place in the town's economic and social structure by being successful at business, carefully managing their money, buying up large tracts of land and expanding into the real estate, banking, and insurance businesses. ...

As can be imagined, politics was always a topic of conversation among the Watsonville Croatians. Even in the 1930s, they would hotly debate old-country historical politics. In Watsonville, the arguments usually centered around ideas about communism versus ultra-nationalism or pro-Austrian versus anti-Austrian. These sometimes volatile discussions often took place in the park on Main Street on Sunday mornings when the Croatian men, dressed in their Sunday suits, would hear the latest news and talk about international politics while their wives and children were at Mass. In this way, they kept each other informed about the latest political changes in their homeland and throughout Europe. ...

Croatian Food

[Watsonville resident] Helen Ostoja recalled that, "You could always tell a Slavonian's house because they all had kupus (a form of kale commonly grown in southern Croatia) growing in their yards. Sometimes they even grew it in front of their houses instead of a lawn. White picket fences surrounded yards filled with kupus. We ate a lot of it, boiled and drizzled with olive oil." Fig trees and rosemary bushes were other common identifiers of Croatian homes. Figs grow wild all over the Konavle region and rosemary is commonly used with a mixture of garlic and olive oil to prepare meats and fish for grilling.

Helen went on to say, "Everyone had a vegetable garden in their back yard. They grew onions, potatoes, and carrots. Each family had their own chickens, eggs, turkeys, and rabbits. We canned a lot of fruits and vegetables and little white onions." Andrew Mekis recalled that, "Several families had their own smoke houses and they would let other families use them to smoke their meats. This was not a luxury item like it is today--we all smoked our meets regularly. We would smoke ham (prsut), goat (kastradina), sausages (kobasica), and (devenica), the later of which were blood sausages. To make devenica, you would take the lining of a pig's stomach and stuff it with corn meal and smoke it." Mary Scurich Farris, Luke Scurich's granddaughter, agreed with these recollections and said everyone grew kupus and made their own prsut and kobasica. Andrew also talked about how Croatian men would make their own wine and grapa or rakija (brandy made from grapes and often flavored with grasses). He said, "My father would make grapa once a year in the kitchen in the middle of the night (this was during the prohibition). He'd start at nine p.m. and made it all night long." [Register-Pajaronian editor] Ward Bushee wrote:

During prohibition, some Slavs took to the Pajaro Valley hills where they operated stills. Even afterward [after prohibition] a few Slavs continued to make wine and brandy [grapa] in small quantities for sale among the Slavs, a practice that has attracted the attention of federal agents at times. The Yugoslav skill in this field was admired, even by the agents, one of whom told me after a raid in the 1950s that the brandy that had been seized was by far the finest he had ever tasted.

... The Croatian-American diet remained essentially Mediterranean. There was bread and coffee for breakfast, even for the children. A workingman's lunch was frequently a bottle of wine, Romano cheese (hard Monterey Jack), and bread. The men would soak their bread in the wine and eat it. ... Lunch at home was often soup, or cheese and bread and a pickle. Sometimes it included hard- or soft-boiled eggs or an omelet with onions. For dinner, soup was always the first course. The second course would be the meat and vegetables that had been cooked in the soup. ... However, the most common meals were kupus cooked with potatoes and kabasica or pasta cooked with a meat and tomato sauce (makarula). Everyone drank wine with dinner; even the children were served watered down wine, which was called bevanda. ...

Visiting Friends and Neighbors--A Way of Life

Like everywhere else in the world, life was quite different in the 1920s and '30s--before television. People did much more of what had been done traditionally: they would visit each other to catch up on the latest news and gossip. ... [P]articularly on spring and summer evenings, the whole family would go visiting. Again, no appointments or phone calls preceded the visits. The family would finish dinner and from around seven-thirty to nine p.m. they would call on friends or relatives in the neighborhood. When they arrived, they would be served cake or canned fruit and coffee. The parents would talk and sometimes play cards. The men would often have a shot of grapa.

As a result of these customs, the community remained close, but it also meant that everyone knew everyone else's business. Andrew Mekis recalled, "If you were a teenager, and Mrs. Lasich saw you downtown at two p.m., your mother would know about it by three p.m. But I enjoyed the close-knit feeling of the Croatian community. Everybody knew everything about everyone, but it never bothered me. When I was in my twenties (in the 1940s) and worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad, I had the night shift and I'd get off at seven a.m. When we got off work we'd go to the bars for a couple of hours before going home to bed. When we left the bars at nine a.m. or so, all the Croatian women would be out doing their shopping, and they'd see us leaving the bar. So everyone always knew what everyone else was up to, but we didn't care." ...

Marija Draskovic, a more recent observer of the differences between Croatian and American cultures, arrived in Watsonville as a refugee from Konavle during the recent Croatian War that took place between 1991 and 1995. She said,

In the old country, I do not like the way every aspect of a person's life is pre-determined according to tradition, including who will attend weddings, what the children will be named, and what their educations and careers will be. I love tradition, but tradition does limit you a lot, so I've kept the traditions that I like and I've dropped the ones that I don't like. You can do that in America, but you cannot do that in my country.

Marija believes that the hardest adjustment she has had to make in America has been losing the social life that she enjoyed in Croatia.

Here I just wave at the neighbors but I don't know all of their names. In my country, your neighbors are closer to you than your family. Every day they will come to your house and have coffee. If you need any kind of help, they will help you. We don't move as much as Americans do, so you really build up relationships with the neighbors for years. I also like the way Croats entertain. You don't work when you come to my house, and I don't work when I go to yours. Otherwise, everybody is working all the time! We don't have potlucks in Croatia.

John Basor agreed. In 1991, John was interviewed about his home in Konavle and said,

People in Croatia, especially in the area I come from [Konavle], find time to get together, to visit each other, to have a glass of wine or a glass of brandy. People walk more. In the city of Dubrovnik the Main Street is only for walking. So people run into each other, get together without making plans. They stop by a café, meet somebody they know, they chat, talk about sports or politics or whatever it might be. I miss that here. I like to socialize, I like people, I like to pass the time with other people. And Jelka, my wife, she misses it too. Over there she would walk through the village of Gruda and run into her friends without making a phone call or an appointment. People get out of their houses more regularly and get together informally. ... People here get involved in too many things. People over there work real hard in the fields, but they take time off to rest or go to the beach, or to a festival or something. People end up having more time. ...

Photograph from Pajaro Valley Historical Association

Fruits of their labor: Croatians worked in and often owned the famous orchards of the Pajaro Valley. At the turn of the century, some 4,000 rail cars of apples left the valley each year, bound for points all over the United States.

Conclusion

From Chapter 7, 'Becoming American'

... Clearly, the Croatian immigrants who came to the Pajaro Valley had a tremendous impact on the culture and economy of Santa Cruz County, but their speculation on apple blossoms before there was fruit on the trees, and the vertical organization they developed within the apple industry, would become models for handling fresh produce in California and throughout the nation. For many years, Watsonville's Croatians dominated the apple business in California and helped to form the foundations for the nation's fresh fruit and produce delivery systems that are still in place today. They truly turned blossoms into gold.

The Croatians are just one of the many immigrant groups who found a new life in America and contributed to our nation's growth. In the Pajaro Valley, to be sure, the soil and natural resources are abundant, but it is the mixture of, and the labor of, the Indian, Spanish, Irish, Chinese, Azorean, Croatian, Japanese, Filipino, and Mexican peoples that have made the region and the Pajaro Valley so rich.

BLOSSOMS INTO GOLD will be launched with a booksigning (2pm) and a slide show (3pm) on Saturday, April 11, at the Henry Mello Center, 250 E. Beach St., Watsonville.

A second booksigning (6pm) and a slide show (7pm) follow on Tuesday, April 21, at the Museum of Art and History, 705 Front St., Santa Cruz. Free. The book is available in Santa Cruz County independent bookstores starting April 11.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|