home | metro santa cruz index | features | santa cruz | feature story

Photograph by Kennan Ward

A humble home: When the couple wasn't shooting their film or doing research, they spent time at their cozy Santa Cruz County cabin

Bearing Witness

On the eve of their feature film debut at the Rio, Kennan and Karen Ward talk about their encounters with grizzly bears (and the 'grizzly man' who loved them too much), the ecological perils of anthropomorphism and their 30-year evolution from UCSC students to acclaimed chroniclers of global wildlife.

By Bill Forman

At Santa Cruz's De Laveaga Park, a series of signs announce the dangers of parking your vehicle too close to the softball diamond.

"Park at your own risk," they warn. "Balls land in this area."

It's only a few hundred yards away, just past the picnic tables where families are enjoying a sunny Easter holiday, that a more disconcerting posting is located.

"Warning," it reads. "Mountain lion habitat."

Yet few of the dog walkers and other visitors who leisurely stroll into the hills above the picnic area take notice of the posting as they come upon this "open space area where mountain lions have been sighted."

And even fewer stop to read its recommendations for how to behave should such an unexpected encounter take place.

"Back away slowly," the sign advises, each bullet point separated from the next by a four-toed paw print. "Raise your arm to appear larger. Aid young children. Talk calmly yet firmly." And if the lion behaves aggressively: "Yell. Throw anything you can without having to crouch. Fight back but stay on your feet."

Despite such precautions, neither stray softballs nor unseen mountain lions appear to inspire much more than apathy on this lazy Sunday afternoon.

Yet, at least a few who stumble upon them--the mountain lion warnings, that is--view them with a measure of respect.

"The mountain lion was actually hunting me," recalls a visitor named Martin, who's stepped away from the picnic area to read the sign and has ended up recounting his own near-death experience during a hunting trip down in Mexico.

Explaining how he never heard the animal stalking him, nor his hunter friends calling out from a distance, he says it was only a friend's gunshot that alerted him to the danger. Still, he contends, it's territorial instincts that lie behind such an attack.

"You might be threatening their cubs," he says, "or walking past an area where they've buried food.

"They don't want to eat you," he adds, emphasizing the word want.

Although Kennan Ward might have phrased it differently, the sentiment is much the same when he points out how we rarely understand the motivations of other species, let alone our own. The Santa Cruz wildlife photographer, along with his wife, Karen, will celebrate 30 years of working together with the April 20 debut of his first feature-length documentary film, Making Tracks, at the Rio Theatre.

Last Wednesday, I spent a morning with the Wards in their home studio editing room, watching never-before-seen footage in Final Cut Pro and talking with them about everything from filmmaker Werner Herzog and "Grizzly Man" Timothy Treadwell (whom they both knew before his now-infamous death) to the nature of "zoomorphism"and their three-decade evolution from UCSC student and park ranger to world-renowned wildlife photographers.

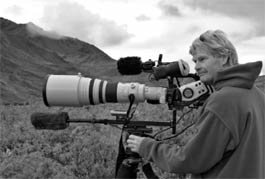

Photograph by Karen Ward

Can you hear me now?: The wife-husband filmmakers used the latest technology in their new film

The Wards have devoted nearly all of the past six years to working on this chronicle of grizzly bear cubs growing up in the wild.

Whether shooting footage in the wilds of Alaska or doing post-production in their home office right here in Santa Cruz's Seabright neighborhood, the couple and their editor Matt Widmann have put together what promises to be a truly stunning documentary.

Despite the fact that this labor of love was accomplished with a remarkably austere budget, Making Tracks' overall production values are impeccable, from the original songs and score by Santa Cruz musician and longtime friend David Lynn Grimes to Kennan's onscreen narration:

"Animals have languages.

If you are visiting grizzly country, it is important to understand the community and the sounds.

"First a ground squirrel will announce your arrival.

Then the other animals will posture with a variety of body languages, each animal reacting to the other.

"The language is universal.

Some animals don't pick up on subtle or obvious body movements.

"So that's body language," says Kennan as we view Making Tracks' footage of a grizzly and a wolf encountering each other in the Alaskan wilderness. "I don't think Herzog or Timothy, if they were in that situation, would have got that message. But you got it, right away."

So what message would Grizzly Man director Werner Herzog have gotten if they'd witnessed that encounter?

"Hostility, anger, conflict!" answers Kennan without hesitation.

And Timothy Treadwell?

"Oh, aren't they cute?"

In fact, it turns out, there was something much more purposeful going on.

Karen: The coyote is trying to chase the bear out of the area, he's being really persistent with something 15 times his size.

And then he backs away when the bear turns around.

But he stayed on him and tailgaited him the whole way.

Widmann cues up another clip and Kennan's voiceover continues:

"When a coyote sees a grizzly approaching, it yelps out an alarm. Usually coyotes also have young of the year. Coyote pups den up in a hole dug into the slope. The coyote will defend its den site even against a grizzly. It helps when a pack of coyotes work together."

In this scene, the tables appear to have turned, as a coyote taunts a seated bear, cub between its legs, as it attempts to swat the coyote away.

Isolated from its context, it's easy to imagine Herzog or Treadwell witnessing the same scene and viewing it through their own predetermined vantage points, as either the cruel brutality of nature or more cute animals playing around in the woods.

In reality, the coyotes have surrounded the bear, who cannot rise up for a single moment to fend off the attacking coyote lest its unprotected cub fall prey to the rest of the pack.

"It's really an intense world out there, and so in that way, Herzog might be right," says Karen as we watch the drama unfold onscreen. "But," she adds, "boundaries are boundaries..."

And in the end, it turns out, a kind of last détente is achieved.

"When the competing animals find a balance," concludes the narration, "they move apart."

Photograph by Kennan Ward

Hunter becomes hunted: Karen and Kennan explain the natural interaction of different predators within the same ecosystem in their new film

Back to Kennan live:

"So then they find that balance.

"So it's not some kind of horror story. It's not even death. It's not that they even, you know, that they even bite."

It's just communication, concludes Kennan.

"It's not life and death all the time," he says. "It's how bears and other animals communicate to each other. It's not this sweet nice thing, because it isn't. Neighbors are competing, they're saying no that's on my property. But there's a simple solution to it. In time, they've sorted things out and the coyotes said, 'OK, we're here, this our den.' And so with a little time, then they just go their separate ways."

The Wards explain that we can learn much more from the behavior of animals if we're just willing to bear witness.

That's where the Wards see the concept of "zoomorphism" (as opposed to Timothy Treadwell's anthropomorphic projection of human traits onto the behavior of animals) coming into play.

"That's the thing: We don't need to be at war. Let's see how things happen. Let's see how things unfold ..."

Don't rush to judgment

"Right. And let the body language tell you something."

"See, that's what those guys missed," he continues. "That's what our president is missing. That's what our society is missing.

"They gotta do something. They gotta answer something. They gotta say, this is the reason. No, it's somewhere in the temperate zone," says Ward, returning to a favorite metaphor about his preference for thoughtful inquiry instead of polar opposites.

"And it's temperate," he adds, "for a reason!"

But it may well be that the most important is the remarkable footage the Wards have captured of grizzlies protecting their offspring, interacting with other species, and even foraging in eerie once-frozen landscapes.

As Kennan says in one voiceover:

"Climatic change has caused the glaciers to rapidly recede, exposing lands that have been under ice for tens of thousands of years.

"The process of new vegetation starts along the coastline. Here and in the intertidal zone, new food sources are now available to the bears.

"Bears prowl the beach overturning boulders to feed upon eels and sand lance.

"The creatures hide in little pools beneath the rocks.

The boulders are big and heavy, but they are no match for the grizzly's strength.

"The retreating glaciers have left sediments. These fine, muddy particles cling to the bear's fur; it also turns the water a greenish color called glacial milk.

On the eve of Earth Day and in this age of global warming, the Wards' feature-length documentary is a tribute to the best motivations behind great documentary filmmaking, as well as a testimony to the lessons we humans can learn from observing the behavior of other species in the wild.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|