home | metro santa cruz index | news | santa cruz | news article

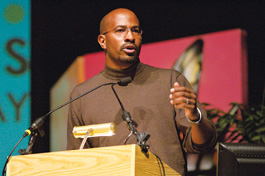

Boot strap pull-ups: Jones may look like he's dressed for a funeral, but underlying his solutions to environmental and social crises is a current of hope that expanded opportunities for unemployed or underemployed poor youth in the environmentally conscious market could be directed to act as a unifying force for the country.

Double Shot

Van Jones believes a national 'green jobs corps' will help solve environmental problems and poverty simultaneously

By Steve Hahn

The mainstream environmental movement, once focused almost exclusively on the preservation of wild lands and conservation of resources, has in the last decade focused more time and energy on issues affecting the urban poor. Environmental activist groups and their allies have increasingly tackled health and quality of living problems in urban areas. Most of these problems are associated with the low air, water and land quality caused by chemical processing plants, oil refineries and similarly dirty industrial facilities predominately found in neighborhoods with poorer populations.

Now, as the United States moves into the 21st century, social justice advocate Van Jones sees a "third wave" of the environmental movement, involving large business organizations selling products that will provide an alternative to fossil fuels and pollution. But this time Jones hopes a more socially aware environmental movement will "raise all boats," and not just leave nice vacation spots for suburbanites.

"We are now in a period of monumental social and environmental crisis and we have limited time and resources to address the issues," says Jones, founder of Oakland's Ella Baker Center, an organization fighting for alternatives to incarceration of urban youth. "So, any solution that gets proposed needs to be able to check off a number of boxes in terms of its value to society. So, from our point of view, focusing on green-collar jobs for urban youth helps us solve a number of problems. It helps us address global warming, poverty, community violence and despair all at once with the same dollar."

Jones cites emerging positions in the job market, such as solar panel installation, organic gardening and energy-conscious construction and maintenance, as examples of "green-collar jobs" that could be staffed by poor urban youth.

In Oakland, he has already started putting his ideas into action. As part of Mayor Ron Dellum's Green Economic Initiatives Task Force, Jones is working on the establishment of the first green job corps that will train socially marginalized groups such as ex-cons, at-risk youth and low-wage workers in the new skills that will drive the alternative energy industry.

This could help foster a socially productive alternative to the vicious cycles of crime, violence and incarceration that ends too often with jail, death or a life underground for urban youth, says Jones.

Call to action: Urban youth activist Van Jones fears global warming and other looming environmental disasters may increase social inequity if the nation's poor are not trained in the jobs of the future.

"I personally felt that it would be very hypocritical for us to say that a kid in the neighborhood who was engaging in economic activity that was harmful, say stealing cars or selling drugs, was doing something wrong," Jones says. "But then to say that when that same kid gets a job in a factory polluting everybody and giving everybody cancer and asthma that they're doing something right."

For Jones, this kind of forward-thinking job training of America's poor represents an evolution of not just the environmental movement but also the social justice struggle, which he has noticed is sorely lacking in solutions to the problems activists constantly bemoan.

"It was very straightforward: What problem are we trying to solve? Well, we want to put people to work, but we don't want to put them to work in ways that hurt the neighborhood," Jones explains. "We want to put them to work in ways that help the neighborhood economically and in terms of public health, spiritually and in every other way."

Once Jones has refined his green job corps concept in Oakland, he hopes the idea will catch on and spread to the rest of the country. Otherwise he fears a vast majority of the population will be left out of the burgeoning green industry, just as the growth of American industrialization in the early part of the last century marginalized migrant blacks in favor of more recent European immigrants.

"The green economy can only work if it includes millions and millions of people; you can't have a 25 percent sustainable economy and go where we're trying to go," says Jones. "It's a shared goal that people of all races and classes can embrace. We haven't had that for a long time in this country. It has probably been since Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were killed in '68 that there's even been a positive center of gravity in terms of what we can all get together around."

Van Jones speaks on Wednesday, April 25, at 7pm at the annual Center for Justice, Tolerance and Community spring lecture in College Nine and Ten's multipurpose room at UCSC; free. (831.459.5743)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|