home | metro santa cruz index | the arts | visual arts | review

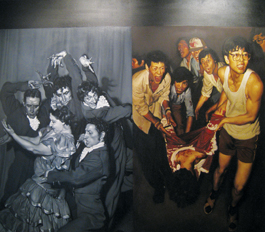

Chen Danqing, 'Expressions,' 1992, oil on canvas. Courtesy of D.P. Fong Galleries

Different drummers: Firebrand Chen Danqing juxtaposes a scene fromTiananmen Square with an image of flamenco dancing.

Change Dynasty

An ambitious exhibit at MAH examines a rapidly evolving China from the Santa Cruz perspective.

By Maureen Davidson

Hundreds of red dots of coiled silky string--flat coils, hot red, various sizes--stick to the white walls and blond wood floor of the museum gallery. Each coil trails a long vivid tail of carmine behind it.

The bubbles of red string emit a color so intense that the dots spring to the foreground of vision and seem to hover effervescently within the brightly lit corner space. It's a spirited work, precise and ebullient, using beautiful materials in a surprising way, promoting cheerfulness. Red is the Chinese color for happiness. Chairman Mao required that it be used prominently in art during the Cultural Revolution.

Beili Liu's installation, Lure #2, does, indeed, raise the spirits and delight the senses without any need to know that the artist was trained in China during the first exhilarating years artists were allowed to travel, work and exhibit with relative freedom of expression. That's relative freedom compared to being sent--as "effete intellectuals"--to remote villages for "re-education" by the peasant farmers who were heroes of the state during Mao's Cultural Revolution; or compared with the heady resistance of students and artists that was abruptly and violently repressed at Tiananmen Square; or compared to the all-too-brief triumph of the China/Avant-Garde exhibition of 1989 mounted in Beijing by artists from all over China, in defiance of regulations, then shut down hours after opening.

Closed/opened, repression/rebellion: the story of modern art in China is a story that spans only three tumultuous decades. But it is also the living, growing tip of a 2,000-year tradition.

Beili Liu has accessed old materials and cultural information in creating a work that is completely modern but which espouses the most basic principle of Chinese art, outlined by Hsieh Ho in the fifth century: "spirit resonance," the energy living within the work. Lure #2 generates enough energy to lift all spirits.

The artist now lives in California. She writes, "Coming from the east and being in the west, the two value systems in my life inevitably contradict and influence each other. ... I see a cycle of remembrance, adaptation, avoidance, and rediscovery of the two cultures in my creative path."

This cycle, these contradictions and influences, are the subject of "Ying: Inspired by the Art and History of China," an ambitious exhibition at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History that examines the exchange of influences between America and China as seen from the lens of a tucked-away coastal county on the eastern rim of the Pacific.

Familiar Forms

Ying is a Mandarin word for "welcome." A mobile sculpture by Santa Cruz artist Maddie Leeds is indeed a dramatic welcome. Ascending three stories in three dimensions, its horizontal gestures are made of driftwood; its calligraphy painted in puddles and curves of bull kelp; its sweeping graceful gestures are trailing banners of long, slender, gently curving Chinese brush paintings. The work is saturated with a Chinese sensibility wielded by the maker of gigantic vessels of Chinese classical style and American muscularity. It's the work of a potter who has studied for over a decade with a Chinese master of calligraphy and brush painting.

Leeds' welcoming scroll is one of many examples of how Chinese art and culture have influenced local artists. Works by Leeds, Gloria Alford, Coeleen Kiebert, Sara Friedlander and other American-born artists are interspersed throughout the museum's galleries along with Chinese traditional art lent by local collectors: classical ancestor portraiture, brush paintings, a reassembled interior of a Scholar's Room with lustrous antique furniture. These works span several centuries and many regions: a thin, very personal representation of 2,000 years of unbroken tradition, but evocative of an aesthetic.

"Ying" is most ambitious, however, as curator Susan Hillhouse endeavors to represent the mix of influences in the works of contemporary artists of China and of Chinese-born artists living in California. She conceived of the exhibition after returning from an extended visit to Qufu and Chengde, where she was fascinated by how the work she saw illustrated the contradictions and influences of the artist's exposure to contemporary art of the West. Hillhouse invited 10 Chengde artists to participate in "Ying."

Yiwei Li, Xiaoli Cui and Siyong Ma are landscape artists whose traditional subjects--water cascading over rocks, distant hills, autumn forests--are painted with a dense, highly literal style that chokes the works with almost claustrophobic applications of gouache. However, Liming Wang, in Lone Sparrow, uses this overall density to underscore the subject, which is not so much the tiny sparrow hiding under the protection of huge leaves as it is the creature's tenuous place in the large world. While Western in the use of paint, this work retains the essence of Chinese philosopher-painters whose works were not "about" birds, mountains or rocks, but rather about the spirit of a place and time.

The most vigorously modern of the work from Chengde uses the most traditional of Chinese art forms. Brush painting--ink on rice paper or silk--has been the primary medium of Chinese art for millennia. With techniques wrapped in elaborate systems, philosophies and theories, centuries of artist-scholars have sought to perfectly express a world in the simplicity of a breathless moment.

Xiao Yu Tien paints the most traditional of subjects in Philosophers in the Trees. Wielding the brush with exquisite control, the artist integrates the puddly wash of tone and the fast black lines of the brush tip in a composition that could well be ancient--or alternatively live happily in a room of German Expressionists. Beyond the works from Chengde are powerful examples of major Chinese artists whose expressions are not as mild.

Tradition Departs

Hung Lui was "re-educated" during the Cultural Revolution, then trained in the approved socialist realist style of painting that was used by the state to glorify communist ideals. Now living in the United States, the artist uses gigantic photographic images dripped with linseed oil in a style that became popular in the Beijing Avant-Garde movement. Her Chinese Profile #2 is a massive portrait of a beautiful woman in traditional dress executed in luscious, wet, loose brush strokes to achieve not so much a representation as an impression of tradition moving out of the picture.

Wang Ningde, arguably the most important Chinese photographer of this era, stages black and white photographs of people, often in dress that evokes their status, always with eyes closed, to represent the de-individualization of Chinese citizenry. At the same time, by such generalizations, he conveys the touching irrepressible humanity of his subjects.

Chen Danqing was of the generation of rebellious artists emerging from the approved painting academies but not content to paint what was considered appropriate subject matter. As early as the late 1970s he created a sensation by a series of paintings of Tibetan "ethnic minorities." In "Ying," his startling Expressions uses the tumultuous realism of a Delacroix or a Caravaggio to juxtapose a bloody incident in Tiananmen Square with a monochromatic portrayal of the more acceptable passion evoked by a group of flamenco dancers.

After Tiananmen, a new style emerged in China, reacting to the suppression of ideas. Borrowing from pop culture, it uses flat backgrounds against which gross, vulgar figures are engaged in meaningless, often violent acts. This style of "Cynical Realism" is represented by the works by Zhou Lu. Little bald-headed hooligan boys gripping 7-Up bottles or other icons of the West show the graphic influence of video games. According to Hillhouse, these "show underlying tension between West and East, between old and new ... the way China is changing so quickly without time to reflect on ideals and the way one should be in the world."

Pop Zhao is a major force in contemporary Chinese art. He recontextualizes imagery from the Cultural Revolution when Romantic Realism was the approved genre with which to communicate communist ideals, showing party leaders and happy peasants living the socialist ideal. In "Ying," Zhao is represented by a suite of paintings that are takeoffs of Mao's Little Red Book--but Zhao offers a yellow and a blue book too. A massive clay Chin soldier dominates one gallery, on the surface a re-creation of a funeral statue of the Chin dynasty, but at closer inspection the armor is emplazoned by a Chanel logo.

Zhao, part of the "'85 New Wave" movement, experienced a taste of freedom that was quickly suppressed. Now he divides his time between China and the United States and is currently working on a major piece for the Olympics. Regardless of his prominence, he has been forbidden to exhibit certain highly political works.

Perhaps the most evocative demonstration of the influence of the West on Chinese art is in the revolutionary use of the old forms of calligraphy and brush painting. These forms were deconstructed importantly in the conceptual work of Xu Bing and Gu Wen Da who emerged from China in the early '90s and achieved world prominence.

Wang Dong Ling lived in Santa Cruz in the mid-'80s. Two of his works completed during that period are mounted on scrolls. The most extraordinary of these, executed in bold calligraphic ink strokes on rice paper, are evocative of Franz Kline's quintessential abstract expressionist paintings. In this interpretation, the explosive action of the calligraphic gesture is the content of the painting.

Ying is a very personal outlook on a huge subject, a conversation with very engaged participants, bursts of information, then long thoughtful silences. It succeeds, within its narrow representation, in showing the diverging influences that make up a global culture.

YING: INSPIRED BY THE ART AND HISTORY OF CHINA continues through June 29 at the Museum of Art and History, 705 Front St., Santa Cruz; 831.429.1964. On Thursday, April 24, at 6pm, SANDY LYDON AND GEORGE OW JR. read from and sign copies of their book 'Chinese Gold: The Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region' as part of 'Ying.' $5 members/$7 nonmembers.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|