home | metro santa cruz index | feature story

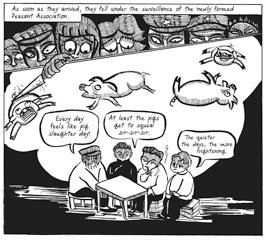

FRAMED: In what could be a 'Maus' for the Cultural Revolution, Yang documents the suspicion and paranoia of Mao's China.

Still Life

Monterey Bay writer/artist Belle Yang updates her family history with the graphic novel 'Forget Sorrow: An Ancestral Tale'

By Cat Johnson

NEARLY 20 years into her career as an artist and author, Belle Yang found herself at a creative impasse. The UCSC graduate had written a prose-style memoir of her father's family titled Forget Sorrow: A China Elegy, but she was having difficulty getting it out into the world.

"It was considered too quiet for the market," she says over tea. "There are a lot of books about the abuses of the Chinese people, but mine was more about the texture."

Yang's agent, however, saw potential in the story, and urged her to re-create it as a graphic novel. The resulting book, Forget Sorrow: An Ancestral Tale, has captured the attention of lit critics and graphic novel enthusiasts alike, and has Yang being celebrated as a natural in the genre. "My editor says I've taken to it like a duck to water," she says with a smile.

Born in Taiwan, Yang emigrated with her parents to the United States, via Japan, when she was 7 years old. She says she understands what it is to be a stranger in a new country, relying on stories from home for a sense of identity.

"When you come to a new country, the stories become like landfill," she says. "You pull soil from the old country so you can have a ground here." In Forget Sorrow, Yang weaves the Old World stories of her extended family with her own experiences as a young immigrant in a new world. Hers was a challenging situation, intensified by her quiet disposition. She says her feelings of being out of place contributed to her decision to attend college in Santa Cruz.

"I wasn't very talkative, nor was I in my element," she says. "I never fit in anyplace, so I figured I may as well be a banana slug."

When, as a college graduate, Yang was forced to flee an abusive boyfriend-turned-stalker, she moved back into her parents' home. Through the stories her father told, she began piecing together her family's history, from her Manchurian great-grandparents to the devastation of war and the Cultural Revolution to the powerlessness her parents felt trying to create lives in a new country. She wrote the stories down.

In 1986, she traveled to Beijing to study traditional Chinese painting, but her studies were cut short three years later by the Tiananmen Square Massacre. That's when she decided that she needed to share her stories with the world. "I didn't want to waste my voice," she says, "because I saw other people silenced, and I had been silenced."

HOMEBODY: Belle Yang at her home on the Monterey Peninsula

Word Pictures

Through the creation of Forget Sorrow, Yang says, she attempted to write sorrow out of her father's life. In doing so, discovered her own strength.

"You come to the U.S. and you don't speak English; you have no voice," she says. "My father and mother lost their voice in coming to this country. And when you lose your voice, you lose your individuality." She connects the silencing of immigrants and victims of abuse with the silencing of an entire country.

"I lost my voice to this man, being locked up and abused, and with China being locked up and abused, I saw a very strong parallel," she says. "But I was able to overcome my fear, and I gave voice to my father and mother, and they were able to give voice to others who had been lost in war."

Using the graphic format to tell her family's story signifies a return to Chinese graphic art and calligraphy, which Yang considers the mother of all arts. "Chinese written language has retained the artistic element, and in that sense, the graphic novel, with its art and words, is a perfect fit for me," she says. She goes on to explain that Chinese horizontal scrolls were meant to be unrolled—not all at once, as we see in museums today, but one segment at a time in a style that foreshadows motion pictures, Japanese manga and comics.

The success of Forget Sorrow has Yang's publisher already asking for the next book, which will be a graphic memoir of her mother's family. "I'm grateful for having this wave of graphic novel wash over me," she says. "I feel like a kid again."

But Forget Sorrow was 14 years in the making, and she doesn't want to rush the next one.

"I don't want it to be hurried and weak. It won't take 14 years, but it will take a good long time," she says, and adds, "It will take as long as it takes."

BELLE YANG reads from 'Forget Sorrow: An Ancestral Tale' on Thursday, June 10, at 7:30pm at Capitola Book Cafe, 1475 41st Ave., Capitola. Free. 831.462.4415. She signs copies of 'Forget Sorrow' on Wednesday, June 30, 5–7pm at Atlantis Fantasyworld, 1020 Cedar St., Santa Cruz. Free. 831.462.0158

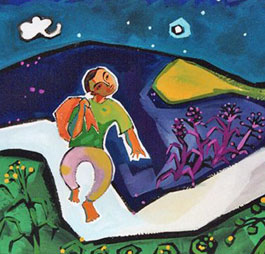

COLORFUL CHARACTER: The Odyssey of a Manchurian' tells the story of Yang's father, who fled his village as a teenager.

Village Voice

BELLE YANG'S commitment to using her voice as a tool to promote understanding is apparent in all of her work. It shows up in stories for children—about acceptance, differences, immigration and fitting in—and in her books for adults that carry the reader through her father's journey of growing up in China, coming of age in violent times and being forced to leave one's home. Here's are three of Yang's books that deal specifically with home, family and immigration.

Hannah Is My Name

(2004) A glimpse into the life of an immigrant family waiting for their green cards in San Francisco, Hannah Is My Name is a picture book that provides children and adults with a gentle reminder that trying to create a life a new country can be a great emotional and physical challenge.

Baba: A Return to China Upon My Father's Shoulders

(1994) In Baba, Yang weaves together—through her words and paintings—the colorful characters, landscapes and events that informed her father's early life in northern China in the 1930s and '40s, within the House of Yang. In the preface, Amy Tan writes, "[Yang] has created a world we can lose ourselves in, and when we emerge, we are all the better for it."

The Odyssey of a Manchurian

(1996) Recounting the story of her father's escape, at age 17, from his village in Manchuria and subsequent journey to southern China, where he hoped to find safety, Yang provides a narrative of the devastating hardships and losses that befell the Chinese people during the revolution and struggle for power between the nationalists and communists. Seen through the eyes of the nonpolitical people who were the victims of suspicion, violence, theft, paranoia and starvation, Yang demonstrates once again that nothing is more political than the personal.

Send letters to the editor here.

|

|

|

|

|

|