home | metro santa cruz index | news | santa cruz | news article

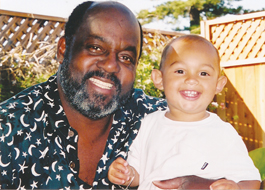

Power to The People: Longtime activist Tony Hill (1945–2007) with his grandson Zavier. Hill fought for affordable housing, meaningful improvements in race relations and more respect for marginalized people.

A Presence Missed

Santa Cruz locals remember a champion of the underprivileged

By Geoff Dunn, George Ow Jr, Deanna Purell, Larry Pearson and Paul Wagner

Tony Hill, who passed away from a massive heart attack last week at the age of 62, liked to say that he had moved as far away from the mean streets of his native Harlem as he possibly could. As he gazed out across the waters of the Monterey Bay or sat in the back yard of his West Side home or enjoyed the company of his friends, he would often marvel at how far he had come from his painful, impoverished childhood in New York City.

"I have arrived," he would announce, his graveled accent always bearing the urban landscape of his youth. "And I came a long way to get here."

But Hill knew that others in Santa Cruz had not arrived—or worse yet, were being forced to leave. For the better part of the past quarter-century, Hill dedicated his life to championing the plight of the poor and dispossessed and underprivileged in Santa Cruz County. At the time of his death he was co-producing a television series at Community Television called Sustainable Santa Cruz, a production that will now be dedicated to his memory.

Born in May 1945, at the end of World War II (he was a proud Gemini), Hill came of age in the aftermath of the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which ruled that racially segregated schools were inherently unequal. He became one of the first group of African American students bused into New York City's white neighborhoods to facilitate racial integration. This experience had a profound and defining influence on Hill, and it would shape his social outlook for the remainder of his life.

After graduation from George Washington High School, Hill attended New York University, majoring in both psychology and business, and then headed west in 1972, first to Los Angeles, where he began working with troubled teens and where he also met his future wife, Melanie Stern. He arrived in Santa Cruz in 1977, once again working with underprivileged youth, and then in 1983 he was named Community Relations Director for Group W, then the county's cable franchise operator. Almost immediately he established KRUZ-TV and directed the station's energies toward supporting local high school athletic programs. From that point on, he became a dominant figure and a prominent voice in the community.

But his presence also manifested itself in subtle ways. An ardent basketball fan, Hill served for many years as a referee in local high school and adult city leagues, through which he built a series of lifelong relationships and networks. Hill was a practitioner of an innovative social technology called "True Colors," which enabled him to break down walls of power and intolerance, prejudice and just plain pettiness in bureaucratic structures. He did organizational development work for private business, nonprofit organizations and government agencies throughout Santa Cruz County and the Western states. His consulting business, Access Unlimited, was booming at the time of his death.

But it was through his public persona as "the conscience of Santa Cruz," as the Santa Cruz Sentinel accurately dubbed him, that Hill was best known to the community. He called it like he saw it, and he was never afraid to chastise the dominant political establishment in Santa Cruz County for emphasizing environmental sensibilities over social concerns. He liked to "break paradigms," find "win-win" solutions and "celebrate diversity," and he preferred the concept of a "Declaration of Interdependence" over one of independence as humankind entered the new millennium.

As a man, Hill was joyous and loving, fierce and passionate. He had a big laugh and a bigger heart. He was a loving husband to his wife and companion Melanie Stern, and the patriarch of a close-knit family that included his beloved daughter, Tara Kemp, her husband, Josh Kemp, and their two children, Zavier and Imani, whom he thoroughly adored during these last years of his life.

Tony Hill was also one of the closest friends I have ever had. He was mentor and confidante, court jester and older brother, and always the bearer of hard love. He both gave and demanded absolute loyalty. I shall miss him the remainder of my life. The void he leaves is vast.

—Geoffrey Dunn, filmmaker, journalist and lecturer in Film and Digital Arts at UCSC

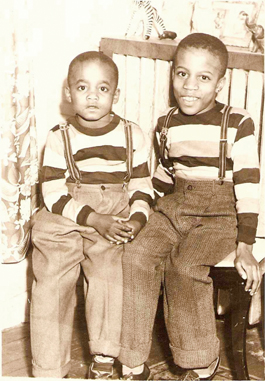

Short Pants: Tony Hill, left, and older brother Lester in Harlem, 1951.

My friend Tony Hill came from black people who survived capture and brutal shipment to America, black people who survived 300 years of slavery. His father fought in Korea, a tough and miserable war, but came back home unable to find steady work. A veteran, yes, but overridingly disadvantaged in terms of employment and finding a place to live. The odds were overwhelming and the despair of not being able to provide for his family adequately drove Tony's dad to alcohol. If you think that race doesn't matter, like many in Santa Cruz do, then you are privileged beyond what you can imagine.

Tony worked hard for education, housing and jobs for African Americans because he felt that behind Santa Cruz's progressive and liberal image was an uncaring barrier of industrial-strength institutional racism.

Tony was an essential part of the team that brought what is now an accepted West Side institution, the Longs Drug Store, to Mission Street. Over the years, scores of black people have worked there— as well as many more white people, many Latinos and some Asians. Tony was an essential part of the 1010 Pacific and Shelter Cove apartment projects that brought over 300 livable units to Santa Cruz.

Most of all, I will miss having breakfast with Tony at the Walnut Avenue Café, the Dream Inn or Gilda's on the wharf. His warmth, spark and love were such a comfort to me as we laughed and solved the problems of the world. It won't be the same, for sure.

—George Ow Jr., businessman

It was my third or fourth meeting as a planning commissioner. I quietly observed the public and other commissioners, feeling both intimidated and fascinated with the process. I knew the material and shyly offered my opinion only when necessary, but no more.

During the break a man stopped me and said, "It's good to see you up there. You're an intelligent person with a lot to offer. You're powerful. Don't let anyone define you. Don't let anyone take your power. You have a lot to say. Just open you mouth and own your power."

I thanked him and took a few steps back toward the podium. I stopped someone in the audience and asked, "Ah, who is that man?" Oh, that's Tony Hill, he replied.

But for that simple encounter with Tony, I might have resigned from the commission. I was an outsider in every way. I was the only African American woman to sit on any body with significant power, and I was not aligned with any local political group. Inclusion was something that Tony preached and practiced every day. He reached out to everyone. And he encouraged the same from his friends.

—Deanna Purnell, Santa Cruz Planning Commission, 2001–2006

Tony Hill was about unity. He believed that a well-functioning community could achieve everyone's important goals. Economic growth and social justice were not opposed, they were in concert.

He cared about the quality of conversation. If we came from a place of respect and not of blame and shame, wonders would ensue. A most insightful man, he was a gifted mediator. I had what I believed to be an intractable personnel problem at work and asked his help. In a few meetings with the relevant department, a solution was found. The workplace once again became a positive place, each person was esteemed, no jobs were lost.

He quietly helped many people. His door was always open, his time never short, his schedule never full. He always believed things would be better some day and committed his life to making that happen. He lived his beliefs and thus inspired everyone around him.

Although Tony's life was too short, it was very full. His blessings included an amazing wife, a wonderful daughter and son-in-law and two darling grandchildren. A man of love and commitment. A life well-lived. There was only one Tony Hill in Santa Cruz, and we are diminished without him.

— Larry Pearson, co-owner, Pacific Cookie Co.

Thus spake, in a phone call in March of last year, the Buddha known as Tony Hill:

"Gotta tell you, I just came back from the county building. You know those Watsonville folks who've been trying to build the job base in their city, and the north county white power structure told them to do this and that first, and they did it?

"Well, today they were back— 30, 40 Latinos, Filipinos, Japanese. Still having to stand there and plead for hours with the same people. Because, of course, they can't be trusted to make decisions themselves."

(Well, I offered sarcastically, they're people of color.) "Yeah, but it's more. People of color, or poor folks, or rich folks, or students, or gay folks, or women, or employers, or 'developers' or whoever.

"Doesn't even matter who, because it's not about who, it's about power. It's about using power over, about overpowering people we don't think are worth being in relation with, instead of using power with, which means reaching out to include everyone in the discussion.

"And this is why the real conversation we need to have, and keep having, isn't about water or growth or environment or economy or the boardwalk or Watsonville land; it's about power, and whether we use our power to uplift and include, or use it the way it's usually used: to dominate and control.

"Because when you cut through the 'issues' and the 'crises' and the political self-descriptions, that's always the fundamental issue.

"Always."

— Paul Wagner, journalist

Memorial services for Tony Hill will be held Friday, Aug. 17, at 12:30pm at the Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium, followed by a reception.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|