home | metro santa cruz index | movies | current reviews | film review

DVD Reviews

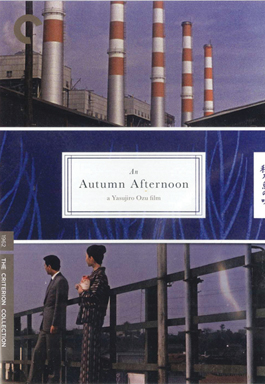

Yasujiro Ozu's 'An Autumn Afternoon,' 'Delicatessen' and 'Mobile'

An Autumn Afternoon One disc; Criterion Collection; $29.95

Gene Hackman's detective in Night Moves joked that an Eric Rohmer movie is like watching paint dry. It could also be said that a Yasujiro Ozu movie is like watching high-gloss lacquer dry. But the attention to minute detail and the sometimes glacial shifts in emotional dynamics seen in both Rohmer and the great Japanese director are worth cherishing--they reward the contemplative moviegoer. Ozu's last film, 1962's An Autumn Afternoon, shows that the director was as comfortable with color composition as he was with black and white. The opening shot sets us near a factory with red-and-white striped towers like industrial candy canes. The apartments his characters occupy are accented with brightly hued touches--especially a space-age red and chrome vacuum cleaner--that contrast with the button-down gray suits the men wear; they all look like extras from Mad Men. The story--simple in outline but complex in implication--follows Mr. Hirayama (Chishu Ryu), a widower who lives with a bumptious son and a dutiful daughter, Michiko (Shima Iwashita), both in their 20s. Another son, Koichi (Keji Sada), lives downstairs with his wife, Akiko (the wonderful Mariko Okada). Mr. Hirayama's friends all urge him to marry off Michiko before it's too late, even though she shows no urgency in that department. Mr. Hirayama doesn't really want to let go of his comfortable familial relationship; it represents a sense of continuity with his wife, whose memory still lingers. In a larger sense, nostalgia for the old ways tugs at many of the characters. In one scene, Mr. Hirayama and a stranger sit in a bar and wonder what the world would have been like if Japan hadn't lost the war. Eventually, an arranged marriage takes place, and it is a tribute to Ozu's deference that we're not sure if this represents a happy ending or not. In its delicate way, this is a comedy. One of Mr. Hirayama's colleagues has gotten remarried to a much younger wife, and several jokes about a kind of herbal Viagra fly freely. Michiko's stay-at-home brother keeps ordering his sister around, but the traditional roles can't hold, and she gently deflects his foolish masculine prerogatives. More overtly, the tart-tongued Akiko tries to curb her husband's foolish excesses, like the set of golf clubs he covets instead of the refrigerator they need. Unobtrusively, Ozu sets his camera a little low, as if the viewer were sitting cross-legged in the Japanese style. Most of the shots are held a beat longer than you might expect, with almost no tracking shots. And yet the film never feels static; the action proceeds with a natural fluidity that doesn't need artificial dramatics. This Criterion Collection, beautifully restored, includes audio commentary with film historian David Bordwell, an interview with some French critics, a documentary about Ozu and a booklet with articles by Geoff Andrew and Donald Ritchie.

(Michael S. Gant)

Delicatessen One disc; Lionsgate; $19.98

A small chunk of 1950s France is seemingly stuck in a hellish dimension: a one-building slum languishing through the total war between carnivores and vegetarians. A Mussolini-faced butcher called Clapet (Jean-Claude Dreyfus) sells a kind of pig meat to his oppressed customers, who are too hungry to care where that meat comes from. An ex-circus performer (Dominique Pinon) arrives, the surviving half of a monkey act that met with misfortune; the unlikely hero ends up being the only one who can outwit Clapet and his cleaver. The ogre's pretty daughter (Marie-Laure Dougnac), a near-sighted Miss Magoo, teams up with Pinon to make for the most diminutive couple since Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake. Some influences can be discerned in this 1991 midnight movie by the team of Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet. The maws of ducts and sliding shots of conduits seem out of David Lynch, and a swamped basement full of snails and frogs looks like the finale of Greenaway's A Zed & Two Noughts. There's also something of Tati in the swift, pantomimed anti-jokes and in a symphony of squeaky bedsprings. Bittersweet nostalgia gilds this carnivorous comedy. And the director's short-lensed emphasis on the gentleness of faces shows the intent is more circusy than ghoulish. It wouldn't look as good as it does without supporting work by Silvie Laguna as the moony would-be suicide or with Karin Viard as a bosomy, carnivorous tramp with one of the most nasal working-class Paris accents yet heard. This masterpiece of intricate dark fantasy looks all the better when contrasted with Jeunet's later saccharine hit Amélie. The extras include a commentary track by Jeunet; the director claims his inspiration was living in a flat above a pork butcher's shop, where the sound of sharpening knives jarred him awake every morning. Fine-Cooked Meats by Diane Bertrand is a no-narration short film observing the work on Delicatessen's sets, including Pinon's takes and retakes of his bubble magic. And Jeunet's personal files of tapes include a lively improv by Laguna.

(Richard von Busack)

Mobile Two discs; Acorn Media; $39.99

Here's a great idea: Fed up with cell phones, somebody is blowing up the cell towers of England. Of course, the perp's motives run deeper than just annoyance at loud talkers, but still, it's an intriguing jumping-off point for this superior British thriller, produced by ITV1 and first aired in 2007. Packaged in four segments of 50 minutes each, the miniseries proceeds as an overlapping backward revelation. Each episode introduces new characters and doubles back on what's gone before to reveal crucial plot points from a new perspective. The main protagonists are a police officer (Jamie Draven) grieving over the death of his wife; and two rival telecommunications executives (Keith Allen and Michael Kitchen, the latter famous as the Foyle in Foyle's War)--but everyone has a grudge to avenge or a stake to defend. The cliff-hanger structure makes this worth watching all at once. Unlike a lot of American thrillers, Mobile doesn't tip its hand until the very end.

(Michael S. Gant)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|