home | metro santa cruz index | features | santa cruz | feature story

bound ambition : The Encyclopedia of Earth is a volume of heft and substance.

Got It Covered

Art books you won't want to give away

By Michael S. Gant

Since we're tossing financial lifelines to every industry with enough lobbyists, how about some bailout bucks for a group that really deserves support: book publishers and sellers? According to The New York Times, this coming holiday season looks to be unusually fallow for the people who preserve our intellectual heritage between covers for instant reference, even when the batteries on the Kindle run down.

Books remain a bedrock gift for holiday giving, even if our choices need to be even more carefully targeted to recipients in a parlous economic era. This is the time to consider lasting value in books that mix beautiful images with compelling text. The secret is to be sure to buy from local independent booksellers; they need the juice in these days of metastasizing chain operations.

In the mode of thinking and buying locally, the loveliest coffee-table book of the season is Nature's Beloved Son: Rediscovering John Muir's Botanical Legacy by Bonnie J. Gisel and Stephen J. Joseph ($45, hardback) from Berkeley's Heyday Books, a company with an estimable record for exploring the historical and natural riches of California. From the endpapers, decorated with leaf and fern samples, to the insightful text to Joseph's spectacular photographs (many reproduced full-page size), the book looks like a genuine labor of love, just as Muir's tireless trekking and collecting in Yosemite and other wild places (including even a very different Santa Clara Valley) was a deeply passionate affair: Yosemite, he wrote, "was by far the grandest of all the special temples of Nature."

Muir famously traveled light, but he was rarely without his plant press, and he preserved a substantial harvest of flora, much of it previously unknown. This book uncovers many of Muir's herbarium specimens, which had been scattered into several archives. Using the best of modern technology, Joseph has cleaned up Muir's sometimes dried-out specimens so that they pop from the page with a verdant vivacity. The large ribbed sassafras leaf, for instance, with its simple asymmetrical bilobate shape, looks like a green catcher's glove.

Narrowing the focus from Yosemite Valley to the Santa Clara Valley, consider the many highly localized books issued by Arcadia Publishing in its Images of America series. These uniform, handy paperbacks (all $19.99), collect fascinating archive photographs for various communities, annotated with local lore by people who have lived here, done that--and want to remember all those little details and names that constitute the fabric of a community. Just this year, Arcadia put out South Santa Clara County, which covers South San Jose, Morgan Hill, San Martin and Gilroy. The images range from the Women's Christian Temperance Union to a quintet of happy imbibers at Battista Tognalda's Gilroy saloon. Other recent volumes include The Portuguese in San Jose and Railroads of Los Gatos.

What Nature's Beloved Son does for plants, Tim Birkhead's The Wisdom of Birds: An illustrated History of Ornithology (Bloomsbury, $45 hardback) does for the winged set. The first temptation upon encountering this substantial volume is to thumb through its pages savoring the many color illustrations excerpted from centuries of bird books, from Frederick II's Art of Falconry to Dürer's delicate rendition in three poses of a male bullfinch to Audubon's grand plates. Birkhead, who studies animal behavior, provides a readable history of how the modern science of ornithology developed from the many superstitions, fables and unsteady observations (to a surprisingly late date, many writers believed that some birds hibernated underwater during the winter instead of migrating). His topics cover everything from studies of avian intelligence to breeding strategies.

Birkhead's nomination for an unsung hero of the scientific method is John Ray, a dedicated bird watcher, proto-biologist and author of 17th-century England who "transformed our knowledge of birds from fantasy into fact" and pointed the way to future theories of natural adaptation. He salutes Ray for his "brilliant, readable style," adjectives that apply to Birkhead as well. (As a bonus, this well-designed book boasts generous, nicely proportioned margins and Goudy Old Style, one of the most elegant of typefaces.)

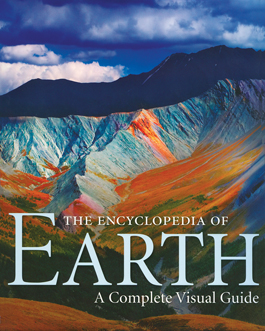

Now that the election has passed and the climate-change deniers turned aside (for a while, at least), it is the perfect time to consider our beleaguered home, the Earth, while there is still time to save it. The Encyclopedia of Earth: A Complete Visual Guide (UC Press, $39.95 hardback) does so with 600 pages of color photos, maps, charts and in-depth text covering the widest possible definition of geology. The book, reasonably priced considering the wealth of illustrations, contains images both awe-inspiring (a gorgeous photo of Arches National Park) and sobering (one map shows the maldistribution of the world's water supplies).

The sections cover the development of the Earth within the universe, galaxy and solar system (big hint: the planet was not conceived 6,000 years ago); the long, slow evolution of life (no need to teach the controversy here), the infinite variety of rocks, minerals and gems; the benign and benighted extremes of weather; the fluid dynamics of the water, from mountain rivulets to the vast oceans; and the effects, deleterious and mitigating, of Homo sapiens on all of the above. The two-page spread on "Changing Weather Patterns" unleashes a Biblical litany of pending disasters that even a creationist might admire: "Droughts, bloods and storms of escalating frequency and intensity have been documented at an increasing rate on all continents during the past few decades." Who's to blame? Us. You betcha.

The biggest book (literally, at 14 by 10 inches) of the season is Art Spiegelman's Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*! (Pantheon; $27.50 hardback). Metro Santa Cruz's resident comics expert, Richard von Busack, describes Spiegelman as the man who showed the United States that the term "serious funnies" wasn't just an oxymoron. This retrospective includes Spiegelman's one-man show Breakdowns, the 1977 prototype of the high art-comic magazine Raw that Spiegelman created in the 1980s, as well as some very funny selections from Funny Animals, Short Order, Arcade and even less-well-known comic books. An early version of Maus has plenty of impact and a lot less detachment. Best of all is Prisoner on the Hell Planet: A Case History. Perhaps nothing Spiegelman has done surpasses this mix of German Expressionist scratchboard, Kathe Kollwitz drawings and EC comics.

(Richard von Busack contributed to this guide.)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|