Lance Linares’ minimalist office at the Community Foundation of Santa Cruz County is a bright, sunlit room of concrete and glass. He sits at a small, simple table by the window, and contemplates his 21-year career as CEO at the foundation.

He took the job in 1995, tasked with growing the foundation’s $6 million in assets, to fund grants to local nonprofits. At the time, he was the executive director at the Cultural Council of Santa Cruz County (now known as the Arts Council of Santa Cruz County), and prior to that, station manager at KUSP.

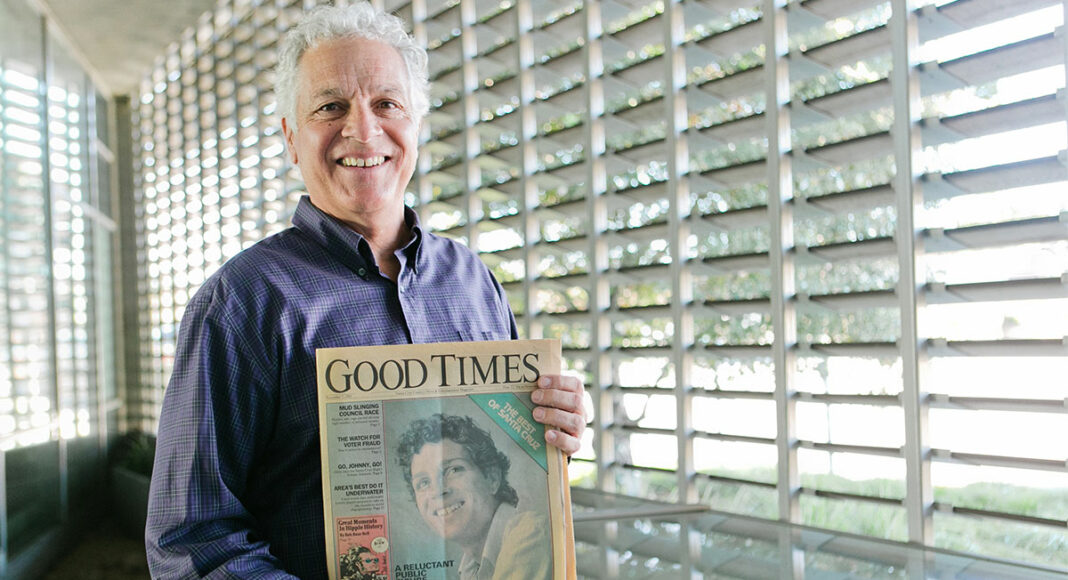

Back then, he had a mop of curly brown hair, which is now white.

“I really only had three jobs in this county, and they’re all really pretty high-profile jobs. Which pretty much means for 40 years, all I’ve been is a boss, starting at age 26 or something,” says Linares. “That’s a long time in a small town to have that kind of presence and responsibility. You get tired after a while.”

When he became CEO, Linares says he didn’t know much about community foundations. Upon his hiring, the first person to call him was Cole Wilbur, then-president of the Los Altos-based David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

“He said, ‘Get in your car and go visit your colleagues,’” says Linares. “This is an incredibly collegial industry. Cole said, ‘The two most powerful words in the English language are ‘help me.’”

Wilbur advised him to “find what people value and honor that,” Linares says.

Behind Linares is a collection of curiosities, evidence of his inquisitive personality. On a shelf above his desk is a neatly arranged row of 18 spherical objects, like baseballs (Linares is a diehard San Francisco Giants fan) and round river rocks. Apparently when people hear that he collects round objects, they give them to him as gifts. For example, in 2009, when construction teams broke ground on the $9 million Community Foundation headquarters on Soquel Drive in Aptos—which undoubtedly will be part of Linares’s legacy—digging crews found a few perfectly-round granite rocks, which they gifted to Linares. Those were too big for his shelf, so he placed them by the window.

The same thing goes for Linares’s steel bottle cap collection, part of which he keeps on a magnetic board behind his desk. His other roughly 9,000 bottlecaps, he keeps at home. Some of the latest additions are from India, brought to him by a foundation board member who traveled there, he says.

Foundation board member Fred Keeley, a former state assemblymember, calls Linares “fun and funny,” and says that people gravitate to Linares, and want to work with him.

Several colleagues say Linares is charming and friendly, yet at the same time humble and private. A Good Times cover story on Linares from 1985, when he was a KUSP station manager, was headlined “A Reluctant Public Figure,” which is still pretty accurate, Linares says.

“You’ve got to know your weaknesses, and then you hire people who complement what you do,” Linares says. “I’ve been really lucky. I have had a really loyal staff.”

Another thing about Linares is that he’s always thinking ahead, says Keeley. For example, he announced his retirement more than a year before it takes effect, so the organization could prepare. Board members knew months earlier, since he met with each member individually to tell them the news and give them time to envision the direction they’d like the foundation to go in.

Actually, a few years ago, Linares began annual routine discussions on a succession plan for his retirement in board meetings, so talks occurred when not in crisis mode. Linares has presented the model to other community foundations and nonprofits, as an organizational approach to leadership change.

“He was probably doing succession planning about what happens after kindergarten when he was in utero,” says Keeley. “It’s in his nature to get ahead of things. It’s something he’s really, really good at.”

A big part of Linares’ legacy, says Keeley, is the growth of the foundation’s assets during his tenure—from roughly $6 million in 1995 to more than $108 million today. Now more than 60 percent of the foundation’s assets are permanently endowed, which means they make an annual income. This year alone, the foundation has given away more than $6 million in grants.

Linares says he tells donors that endowed gifts to the foundation create a lasting local impact, for whatever purpose donors want.

“You want to save the red-legged frog? We can do that. You want to endow Pop Warner football? We can do that,” Linares says.

The Community Foundation has a list of more than 350 funds, some endowed for specific purposes, such as the Diversity Partnership Fund, which has raised $1 million for local nonprofits working on LGBTQ issues.

The foundation also recently unveiled its Fund for Women and Girls, a $2 million fund whose first project will be a three-year program for middle school girls in the Pajaro Valley.

The foundation hosts 50 trainings a year for nonprofits, including grant writing, board management, and a roundtable for new executive directors. Also, more than half of the foundation’s 9,200-square-foot LEED-certified facility can be reserved as event space by local nonprofits, for a nominal fee. More than 9,000 people have used the building annually since it opened in 2010.

Linares says the nonprofit world has changed dramatically during his career.

“Everyone of a younger age has been affected by nonprofits. That was not the case in the 1970s,” Linares says.

In Santa Cruz County, wealth is unpretentious and philanthropists often fly under the radar, Linares says. Unlike in the Silicon Valley, Santa Cruz County doesn’t have big-money events. Donors are regular people who go to Shopper’s Corner and Gayle’s Bakery, he says.

Santa Cruz County has a reputation for having a high concentration of nonprofits per capita, but it’s simply not true, Linares says. It’s just that local nonprofits have had to be “scrappy and entrepreneurial” to get funding.

Linares says the Community Foundation’s next CEO will need to cultivate the “new era” of donors. The county needs a new Jack Baskin, Dick Solari and Diane Cooley.

“We have to grow our own philanthropy. Home cooking is the best cooking,” Linares says.