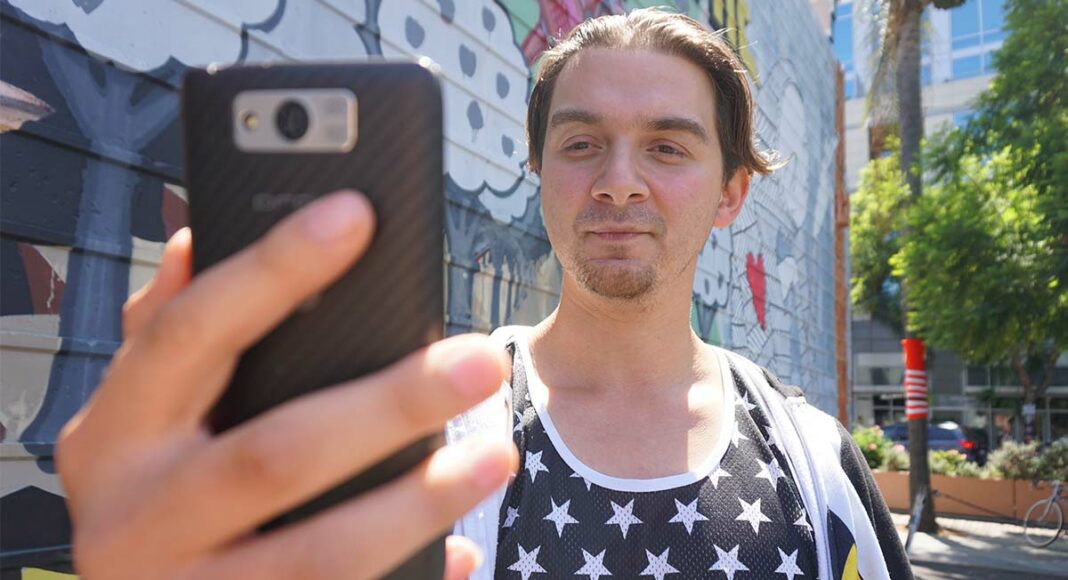

Through the looking glass of his smartphone, Chris Perguidi spied an imaginary monster. He pointed his phone at the purple, googly-eyed Tangela, a vine-tangled critter that lurked just beyond his reach in the digital realm of Pokémon Go.

The 31-year-old Gilroy-based comic book artist had taken the bus to San Jose, in part to hunt for Pokémon. As he turned the corner downtown, he says, a sun-weathered man and bottle-blonde woman across the street began shouting at him to stop recording them.

“I’m not,” he recalls telling them that late-afternoon of July 27. “I’m playing Pokémon Go. It’s a video game.”

Perguidi kept walking, hoping to dispel their anger by minding his own business. But the couple followed, he says. The woman, still yelling, jaywalked to his side of the street and hurled a water bottle at his head.

Perguidi says he turned to leave. But the man—a head-shaven, tatted-up, ropy-armed roustabout—grabbed his shoulder, spun him around and swiped at him with a knife.

Perguidi, a trained boxer and wrestler, says adrenaline triggered his fighter’s instinct. He slapped the blade out of the man’s hand as the woman scratched, bit and pummeled his back. The bald man, furtively re-armed with a knife, cocked a closed fist and swung in a leftward arc just as Perguidi tucked his chin.

Blood began pouring out of Perguidi’s face, which had been sliced into what looked like a second mouth. Had he kept his head up, he says, the blade would have slashed his throat. The knife also tore through his American flag tank top and sternum.

The attackers bolted, police came, and an ambulance rushed Perguidi to the hospital, where a doctor sutured his chin gash with 15 stitches.

Perguidi says he wasn’t engrossed to distraction by the game. But the attack became another cautionary tale about the physical dangers of the latest fad keeping people glued to their smartphones.

Dangerous Game?

Perguidi, who plans to keep playing despite his scrape, will be the first to insist that Pokémon Go—the wildly popular offshoot of the 21-year-old anime franchise—is anything but a deathtrap.

Players in Santa Cruz have been finding electric Pokémon on the wharf, water Pokémon on the nearby beaches and a variety of monsters all over downtown, the Boardwalk and Capitola Village.

Pokémon Go uses geolocation to track players as they move about on a cyber-scavenger hunt for imaginary creatures to catch and train for battle. Google Maps transforms physical locations into a virtual playing field, with “PokéStops” allowing users to buy in-game goodies such as critter-catching red-and-white orbs called Poké Balls, or duke it out with other players at Pokémon Gyms.

Pokémon Go uses phone cameras to superimpose game elements over a real-world backdrop. Prompts on the map turn public parks, museums, churches, cemeteries, sidewalks and university campuses into terrestrial hunting grounds for digital prey, which range in rarity.

Time and topography matter. Aquatic Pokémon like Horsea and Goldeen linger by bodies of water. Ghostly Pokémon, like Gastly and Gengar, emerge after nightfall.

This fictional domain has clashed with reality in a host of bizarre, amusing and occasionally horrifying ways. Before playing, a warning screen cautions users against playing the game in dangerous areas. Shortly after the game launched in the first week of July, groups of people began exploring places they would never otherwise go—often at odd hours.

Earlier this month, someone fatally shot a 20-year-old college student from San Mateo who was playing the game at a park in San Francisco. Preceding weeks saw more than a few players stumble upon dead bodies in their quest for new pocket-monsters. Two brothers in Washington found a .32 Magnum handgun. Ne’er-do-wells have dropped digital Pokémon lures to isolate players and rob them. A budding Pokémon trainer in New York state inspired the no-duh hashtag #DontPokemonAndDrive when he ploughed his brother’s car into a tree in pursuit of a plesiosaur-like Lapras.

Public officials across the state have warned players to be careful and pay attention to their surroundings. A U.S. Department of Justice flier warned of the app’s potential to intensify problems of distracted driving and walking, or children getting lost.

The imagined Poké world ignores cultural context, which is perhaps why developer Niantic Inc. rendered hallowed ground such as New York City’s 9/11 memorial and Arlington National Cemetery into PokéStops.

PokéStops have similarly drawn stampedes of players not only to notable landmarks, but also to random and occasionally inappropriate places. Niantic somehow marked the Holocaust museum in Washington, D.C. as a PokéStop, which drew hordes of players to a memorial for victims of Nazi genocide. Cemeteries have had to shoo away players for invading what families of those buried there consider sacred spaces.

At pediatric hospitals, too, administrators have implored people to resist gaming around sick kids who may want to play but can’t go outside to catch Pokémon.

Pokémon Go’s reliance on users’ personal information has aroused suspicion from civil rights groups, which point out that Niantic CEO John Hanke is beset by privacy scandals dating back to his tenure at Google Maps. The game also raises questions about the ethics of converting public spaces into private profit centers. Video games have existed for more than four decades, but augmented-reality iterations take things a step further.

“It collapses the distinction between the physical and the virtual,” Alexander Ross, a video game commentator, wrote in a column for Jacobin quarterly. “And through the game’s transactional nature, it abolishes the old boundaries of the marketplace. The public park, the community church, the sprawling college campus, and the open square are all commodified with Pokémon Go’s in-game virtual item economy, which supports a very real corporate one.”

Art Walk

Not a week from its July 6 launch, Pokémon Go garnered more active daily users than Twitter and more than $1.6 million a day of in-app purchases in the United States alone. A month out, the game surpassed $200 million in global revenue. Nintendo, which claims a 33 percent stake in the franchise and had been grappling with declining game sales, saw its stock double in value since the app stormed into the mobile marketplace. Conceived by Stanford University student Ivan Lee in 2011, and cultivated by Niantic Inc.—headquartered in San Francisco—into a $3.7 billion phenomenon, Pokémon Go stands to become the most popular video game ever.

By overlaying the physical world with a vast digital dimension, Pokémon Go has added a new class of drifters, pulled into a psychogeographical thrall not by inborn curiosity but by competitive incentive. The game’s design pushes users to notice landmarks they might otherwise drive right past, all to re-up on supplies or battle other trainers.

For businesses or public spaces that depend on walk-in visitors, the sudden surge in foot traffic of gamers trying to fulfill the Pokémon trainer’s edict to “catch ’em all” has been a welcome trend.

Exploring the lush, labyrinthine grounds of the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum in San Jose has become an after-work ritual for Julie Scott, the museum’s executive director of 16 years. After Pokémon Go’s debut last month, she noticed an influx of visitors enjoying the Rose Garden property—guided by their smartphones.

“At first we were like, ‘Wait, what is going on?’” Scott says. “It was very noticeable because it looked like a parade of people walking around in search of something. But they were engaging with each other, and were all so congenial, coming through at all times of day and in the evening. We were so intrigued.”

Rosicrucian staff discovered that the property turned into a Pokémon hotspot overnight. A rare Hitmonchan, a skirt-clad boxer, hovered within the gardens and drew a number of intrepid trainers, Scott says. One night last week, she says, a girl who must have been about 7 years old and knew everything about Pokémon, brought her dad to the park.

“He says, ‘We had no idea you had this labyrinth here,’” Scott says. “We see a lot of that. People come here for a rare Pokémon, but fall in love with the place.”