An Atheist Animal

Jerry McLauglin loves art, aliens, sex and the stellar life

By Sarah Phelan

JERRY MCLAUGHLIN IS AN animal--and proud of it. "Everything that indicates we're animals is buried," explains the silver-haired septuagenarian. "But no matter how we hide and suppress our animalistic urges--be they to fart or fuck--animals we are. Wonderfully elegant and sophisticated animals, but animals nevertheless."

The nationally acclaimed artist smiles, as if amused by those who would believe that the universe revolves solely around them.

"I seek pleasure, avoid pain, and try hard to do what makes me feel good. And for 25 years I've tried to be a success as a painter--not the American definition of success, since I don't have a Mercedes or pots of money. But then again, there are maybe only 20 people in the world whose artistic opinions matter to me. And if they are moved by my work in the best and deepest way, then I guess I am successful."

McLaughlin's works hang in the Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum and the Whitney, but so far commercial success has eluded him. "I've been with the Allen Stone Art Gallery for 15 years, during which time Allen's only sold three of my paintings. But he's never given up on me," confesses the wily conversationalist with disarming honesty.

He pauses, leans forward and divulges in a conspiratorial tone, "One of the great universal delusions of painters is that they believe that what they do is original. But I believe myself to be 100 percent original, based on what I do. In fact, I think I'm probably one of the best painters in the world, in the realm of organic-mechanic-futuristic-alien fantasy."

Although the words "starving" and "artist" are virtually synonymous in our high-tech, mass-produced world, McLaughlin nevertheless attributes his lack of commercial success to the style of what he does. "People are put off by it because my paintings have an alien, foreboding, disquieting quality. And I have an interest in science and aliens, in things in other parts of the universe. In other words, in things that aren't popular on living room walls. I'm not interested in painting gumball machines or flowers. My subject matter is frightening, for if we ever faced reality, we'd be forced to admit that at best it's an indifferent universe."

These days, the 72-year-old often thinks about death, but he's not banking on some harp-plucking session in the Great Hereafter. "I'm an atheist. A nice atheist, although I have my crappy side," he says with a gleeful chuckle that sends both eyebrows squirming above his glasses like a couple of frosted caterpillars. "Personally, I hope that I have another 10 to 12 good years left, and in that time I want to do some pretty good pictures. My difficulty with painting is that all too often I call on personal clichés and trot them out. I'd like to learn to pluck, to derive what I do from that sensational artist, Nature, which moves me so deeply. Whereas clichés don't. All they do is titillate."

McLaughlin's endured public indifference to his art for the past 25 years, "not because I'm a hero, but because I enjoy doing what I do--well, at least five percent of the time!" he laughs, adding in a more pensive tone, "In those moments I get some genuine deep nourishment."

But wait a minute! Isn't "getting genuine deep nourishment" exactly what some people would describe as having a spiritual experience? "Let them describe it!" snorts McLaughlin derisively. "The brain is a purely mechanical mechanism, but such an elegant one that what we feel is so complex that it makes us think we're having a spiritual experience."

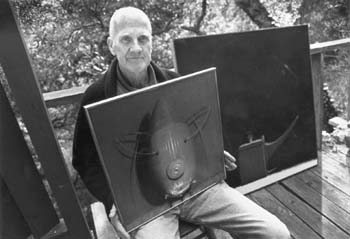

Outsider: Jerry McLaughlin finds his artistic inspiration in sex and science and tends to speculate, in his works, about what alien life will turn out to be.

History and Mystery

ALTHOUGH HE BELIEVES there is no god, the tall, lanky McLaughlin firmly believes in aliens--all the more so because they are so very rarely seen. "Any race sufficiently wise to be traveling vast distances would know that benevolence is the best way to function. For every time a superior race contacts an inferior race, the inferior, or less developed race, is destroyed, simply by virtue of the other's presence. So for our sakes, let's hope this superior race doesn't contact us."

McLaughlin pauses for effect. "It takes enormous amounts of energy to travel. It's four-and-a-half light years away to the nearest star. Life is rare--and the nearest life may be hundreds of light years away. Also, interstellar travel may be an insurmountable problem because, at the speed of light, mass becomes infinite. They call that God's Quarantine, you know," he says, flashing me a mischievous glance to see if I've caught his use of the dreaded G-word.

I have. And I swallow the bait by asking how come he's so sure there is no god, since he wholeheartedly accepts the existence of alien life. McLaughlin answers by referring to Nobel laureate and renowned physicist Richard Feynman, whom he evidently considers a genius.

"Feynman feels that religion is too provincial," McLaughlin begins. "This is an enormous universe, and we're just a small part of it, not even a very important part. The history of the earth is four and a half billion years--just a day in the life span of the universe. And people have only been around for two million years--mere seconds in the history of the universe. Clearly, religion has been manufactured to keep us feeling good about ourselves, but we are obviously the products of evolution. We have become so anthropocentric, when really we're just little creatures scrabbling around on a rock in an immense place."

McLaughlin admits that it was a fascination with this "immense place" that got him hooked on science fiction as a young boy. Then, at age 13, he discovered that science--"both macro- and microscopically"--was so surprising, so beyond what anyone could have imagined, that his interest turned to scientific facts.

While convinced that science is the best path to reality, McLaughlin has never lost his fascination with the unimaginable. In fact, it's what's driven him over the past 25 years to produce huge colorful canvases jampacked with strangely suggestive objects, along with smaller muted portraits of what can best be described as eyeless alien heads and gaping fish mouths.

Photo by Hillary Schalit

Sex, Drugs and Genius

McLAUGHLIN'S NAME first came to my attention not in an art catalog, but in a Metro Santa Cruz article about sex and the senior citizen. "How about sexual experiences, then?" I ask. McLaughlin answers me--with silence. When he finally speaks, it's to admit that things have been a little slow.

"Right now I don't have a sex life outside of my fantasies. I miss having a life partner, though it's a big mystery who we are attracted to," he says. He looks wistful, then suddenly brightens as he recalls how one time a lady who he wasn't interested in--"she had the IQ of tree moss!"--came on to him. "I told her I was very, very kinky in an effort to discourage her. But once she heard that I liked all kinds of wildly imaginative sex, she became even more interested!"

McLaughlin confesses that he's had "lovely things with married women. They all had poor marriages, initially, and I guess I taught them something about life, because it always ended up with them going back and having better marriages! But what was really great about those affairs was that they were friendships free of the constraints of marriage."

So far, he's had two or three relationships that really clicked, affairs in which "we could talk about everything--the world, ourselves, fascinating things in life that are unknowable. Indeed, in my opinion, there are two kinds of people in this world: those who think everything is knowable--I call them crabgrass fools--and those who realize that most of it is unknowable."

McLaughlin was an art director with an advertising company on Madison Avenue until 25 years ago, when he got out of advertising and into prescription drugs. "I headed for California, where I had a network of doctors and pharmacists and could get some very juicy uppers and downers," he recalls.

In the end, he checked into a drug program which he describes as "an awful, terrifying, and remarkably revealing experience. It made me realize that my wife and I didn't make each other happy, and that we never would. It was nothing to do with good guys versus bad guys--she was so pretty, so classy, and had a good mind. But I have a really good mind. And that's my curse. Because it makes it hard to find someone with whom you can feel at ease. I guess it was even harder for geniuses like Einstein!"

When asked where he gets his ideas, McLaughlin lists everything from "the Big Bang 15 billion years ago involving incomprehensible forms that have been on the change ever since" through "the present amalgam of machine and nature" to "the huge, distant sheets of superclusters, the tiny, lovely geometry of viruses and bacteriophages, the intricate beauty of the works in a timepiece--our own astounding mathematical descriptions."

And don't forget the stimulation of "speculating what alien life and civilization will turn out to be." As McLaughlin sums up, "It's a splendid big show for us, with a lot of history and mystery, wonderfully inspirational for a painter. It's where I get my ideas. I could do worse."

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

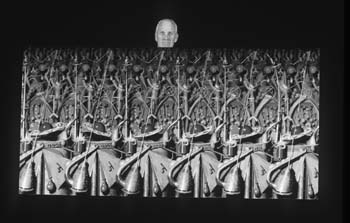

Spaced: Jerry McLaughlin injects the art world with futuristic alien fantasies. His new show opens at the Allen Stone Gallery in New York at the end of this month.

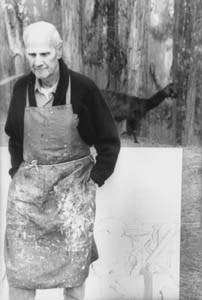

Robert Scheer Something to Goat About: Jerry McLaughlin has endured public indifference for 25 years but continues to find spiritual and emotional nourishment in the works he continues to create.

Something to Goat About: Jerry McLaughlin has endured public indifference for 25 years but continues to find spiritual and emotional nourishment in the works he continues to create.

Although it's been a rough financial ride all these years, the future looks a lot brighter for Jerry McLaughlin. He has an art show opening at the end of January at the Allen Stone Gallery in New York, hot on the heels of the internationally renowned Franz Kleine. He also is looking for a space to live and work. He is offering his services as an art teacher, housesitter and/or tennis instructor in exchange for a room in someone's home or a rent deduction. For more info, call him or his daughter at 354-2569.

From the January 22-28, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)