![[Metroactive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Unlicensed to Drive

Sometimes the complex political battle in Sacramento over SB 60, the bill that would have allowed undocumented immigrants to apply for a driver's license in California, seems abstract and far away. But the tragic case of a man killed by an undocumented driver on Highway 1 makes a compelling argument for ensuring that all drivers can access driver's training, a license and insurance, regardless of immigration status.

By Sarah Phelan

At first glance, the stretch of Highway I slightly north of Moss Landing looks innocuous. Flanked by artichoke fields and steep embankments on both sides, the road slopes and narrows to a single lane in both directions, looking more like a rural road than a highway along which 35,000 vehicles pass every day.

But to the trained driver's eye, the danger signs are there, beginning with warnings to "Turn on Headlights"--advice that stems in part from the fog that often shrouds the pointy-leafed landscape-- and ending with the dividing double yellow line that means no passing at any time.

On a foggy morning last October, Rosaura Luna, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico and mother of five, crossed that yellow line. Why she did it remains a mystery, but whatever her motivation, the move triggered a four-vehicle crash that left Sunnyvale model and motorcyclist David Berridge dead, his Harley Davidson crushed, Luna's Honda sliced in half, a Lexus sedan lying on its roof, and five people, including Luna and two of her children, with minor injuries,

The CHP says Luna, 36, attempted to pass the car ahead just before Jensen Road at about 9:20am. Seeing oncoming headlights, she veered back into the northbound lane, where her car hit the front of a Lexus, which flew off the road and rolled, crashing into the embankment, where its driver, 38-year-old Nuong Thi Nguyen of Marina, escaped with minor injuries.

The 44-year-old Berridge, who was traveling southbound along Highway 1 on his motorbike, wasn't so lucky. As Luna's Honda swerved back into the southbound lane, its back end blindsided Berridge, throwing him into the air and killing him instantly, while his red 1991 Heritage Softtail Harley landed in a crumpled heap at the side of the road.

Meanwhile, Luna's Honda kept going, careening into a 18-foot flatbed truck, which spilt her car in half, hurling the front end--containing Luna and her 12-year-old son, David--into the nearby artichoke field.

Miraculously, all the occupants of Luna's car survived, including her disabled 2-year-old daughter, Kelly Cruz, whose doctor's appointment in Santa Cruz was Luna's reported motivation for getting behind the wheel in the first place. But Luna has languished ever since in Monterey County Jail on charges of vehicular manslaughter, gross negligence and two counts of felony child endangerment, and the lives of Berridge's family and friends have been wrecked, as they deal with losing him in this sudden and seemingly senseless accident.

The Last Morning

In an obituary printed shortly after Berridge's death, his family recalls how, in an audition for CBS's The Amazing Race reality show, Berridge once described his perfect day as waking up, having a Starbucks Grande Mocha with two cups of ice, reading the sports page, and riding his Harley Davidson, enjoying the air and the scenery.

Which means that on the last morning of his life, this world-traveled fashion model was doing what he loved best, as he rode his motorbike first from Sunnyvale to Santa Cruz where he met his brother, Kenny, and then to Monterey, where he and Kenny were going to work on a kitchen remodeling project.

Instead, the brothers last met on the shoulder of Highway 1, where Kenny, who'd been traveling a few miles behind Berridge, had to undertake the heartbreaking tasks of identifying David's body, as it lay lifeless under a tarp at the side of the road, and then calling his family and Berridge's fiancee, Sheree Kirkeby, to tell them the tragic news.

An elegant former model who works at the agency that represented Berridge, Kirkeby, 26, recalls how the man she calls "the love of my life" came back in the house that morning to demand a better kiss or hug before taking off on his bike.

"I was lucky that David wanted to kiss, hug and love me with what turned out to be our last goodbye," she says. "Afterwards, I remember hearing the roar of the bike leave the garage and making a mental note of the sound. And that was that."

That roaring sound marked the beginning of a painful grieving process that has been heightened for the Berridges by the discovery that Luna, who has been sitting in Monterey County Jail ever since awaiting trial, could get as little as one year's probation.

And then there's the tormenting question as to whether all this could have been avoided if California law matched the demographics of the state, in which an estimated 2 million undocumented workers contribute to the economy, yet are not allowed by law to get licensed or insured to drive.

Latino Muscle

On Dec. 12, just two days after Luna first appeared in the Salinas Court House in connection with Berridge's death, Latino immigrants, both legal and illegal, organized a statewide day of action to protest newly elected governor Arnold Schwarzenegger's repeal of SB 60--the state Senate bill that Gray Davis had signed a few weeks earlier in the waning days of his governorship, which would have allowed undocumented workers like Luna to apply for a driver's license, starting Jan. 1 of this year.

Schwarzenegger claimed his repeal of SB 60 was motivated by security concerns, but protesters questioned the logic of a system that allows an estimated 2 million workers to break their backs picking crops, bussing tables and cleaning floors, but shuts them out of the loop that would allow them to drive in a safe, responsible and legal fashion.

They pointed out that in the Monterey Bay area alone, an estimated 20,000-50,000 workers arrive each spring to pick lettuce and broccoli, strawberries and artichokes, crops which rake in $3 billion annually and form the backbone of Monterey's economy. They argue that denying these workers a license in a state where everyone drives heightens everybody's risk on the roads, since an unlicensed, undocumented driver is, by definition, also untrained and uninsured.

Why then all the political pussyfooting around what sounds, at least on the face of it, like a basic highway safety issue?

The answer seems to come down to federal immigration law and heightened security concerns in the wake of Sept. 11, 2001. Take former Gov. Gray Davis' history on the topic. Before he signed SB 60 last fall, he had vetoed several previous attempts to amend the driver's license law, including one that the Senate passed just three days after Sept. 11, 2001.

Acknowledging his publicly stated willingness to provide driving privileges to hard-working, law-abiding immigrants who pay taxes and perform work that many Americans refuse to do, Davis added that "if we are to grant driver's licenses to them because they are workers, it is reasonable to require proof that they are working."

"The tragedy of Sept. 11 made it abundantly clear that the driver's license is more than just a license to drive; it is one of the primary documents we use to identify ourselves," he wrote. "Unfortunately, a driver's license was in the hands of terrorists who attacked America on that fateful day."

Some might say that this latter argument only proves that if terrorists are determined to get around a nation's security measures, they will find a way to do so, but Davis' conclusion, at least at the time, was that future bills "must contain certain common-sense protections if we are to change the requirements for obtaining a driver's license."

All of which left the wooden-faced governor wide open to accusations that he had pandered to the Latino vote when in the run-up to the recall, and with his popularity at an all-time low, he abruptly pledged to sign SB 60, even though questions of national security, not to mention affordable car insurance, appeared not to have been adequately addressed.

Davis is himself history now, as is SB 60. Or is it?

Legislation in Limbo

Dan Savage, chief of staff for state Sen. Gilbert Cedillo, who authored SB 60, explains that Cedillo did not stand in the way of the new governor's promise to repeal the hard-fought-for bill, "because if Cedillo had, the matter would have ended up on March ballot"--a statement that hints at the fear of a backlash against the measure among California voters.

Instead, the matter is back in the hands of the legislature, as Cedillo and others work to come up with solutions that are acceptable to the governor, who claims to have his finger on the people's pulse.

And while some fear President Bush's recent proposals to reform immigration laws are nothing but empty promises to woo Latino voters in an election year, Savage reports that after they were announced, "Gilbert [Cedillo] got a call from Schwarzenegger to say that if the president is saying we've got to acknowledge that these workers are here and give them some legal status, then that has to help politically to get this legislation through."

That said, Savage is quick to point out that Bush's focus is on immigration issues, while Cedillo's is on public and highway safety.

"Obviously, there's a nexus between the two issues, but we're not making the success of one policy contingent on the other," says Savage, noting that one of the central challenges is "to make sure when we license these folks, that they can get insurance."

Courtroom Bombshell

When Rosaura Luna made her first appearance at the Salinas Court House, she had to be removed in a wheelchair, after hyperventilating and almost fainting. Maybe she was reliving the horror of what had happened a month earlier. Maybe she was afraid she was going to get the maximum penalty of eight years in a state prison, followed by automatic deportation. Maybe it was panic at seeing Berridge's family watching her from the public seating.

Whatever the reason, a week later, on a cold and windy Dec. 17 morning, she was back in court, dressed in the jail's orange-and-white striped jumpsuit, her shiny dark hair pulled back off her face.

But this time she kept her emotions in check, as attorney Joaquin Celera, a short balding man in a tweed jacket whom her family had presumably retained for her in the interim, wheeled his files around like a luggage-challenged flight steward on an intercontinental flight.

And, in an emotional sense at least, he was hauling some heavy baggage that morning, first by asking if Luna could get a pass to visit her disabled daughter over Christmas--a request prosecuting DA Steve Somers said was highly unlikely to be granted--and then by revealing that he was going against Luna's wish to plead guilty, claiming that, "not enough investigation has yet been done."

The news hit the Berridge family like a bombshell, with Kirkeby's eyes filling with tears, while Berridge's nephew, Patrick Hanegan, shook his head in angry disbelief.

"There have been no words of remorse," fumed Fanegan afterward. "If I was involved in an accident and killed someone, the first thing I'd do would be to contact family and apologize, write a note or something. And I bet if you asked all the people around here, they'd say they can't afford to get a license and insurance and a car, but now her family is probably paying thousands of dollars for a lawyer. So, it's not a question of money if people wanted it badly enough. And there are other problems. We asked the DA, 'How do you know Luna is her real name?' She has no form of real ID. She can't speak English. She has no photo ID. That's why the CHP took her straight to jail, because they were afraid she might flee the country."

Kirkeby feared Luna's attorney was trying to use the fact that his client is a mother of five with no husband "as a sympathy tactic, a way to get her back with her children. But what kind of a mother is she? And how's she gonna get around as a single mom with five children is not our problem. If she'd had to go through the driving license process, then maybe that wouldn't have happened. David had driven his motorbike for thousands of miles. He'd had that bike since 1991. None of his friends could believe it, but it all happened in a split second. He didn't have a chance. Even in the wildest of scenarios, she initiated what happened. No one else was at fault."

Berridge's white-haired mother, Virginia, felt Luna was guilty of blatant negligence and was lucky that her own children weren't killed.

"She was in a hurry, even though she had plenty of time to get to the hospital, and she was overtaking on a two-lane stretch. She took out a motorcycle, a truck and two cars. She took his life and we got nothing in return."

Catch 22s

Even if one can get beyond the understandably emotional fray surrounding this tragic case to try and understand just how many undocumented--and thus unlicensed and uninsured--immigrants are on the road, it's nearly impossible to get any hard figures.

Steve Kohler of the CHP's Public Affairs says his department only collects data on cars, and basic information such as whether victims were wearing seat belts.

"But in 2002, we gave 82,547 citations for unlicensed drivers," he adds, noting that this number includes legal residents, too.

Over at the state's Department of Insurance, Kerrie Beckstein says an estimated 3 million drivers are uninsured in California, with 8.8 percent in Monterey, though again no one in her department knows what percentage are undocumented, as opposed to simply uninsured.

And Bill Branch of the DMV's Media Relations Department in Sacramento admits that the last time the DMV undertook a study of uninsured drivers was 15 years ago, at which point an estimated 20 percent to 25 percent of all California's drivers lacked insurance.

Meanwhile, Tony Acosta of Citizenship Project in Salinas estimates that 20,000 undocumented workers arrive in the Santa Cruz/Monterey County region during the peak farming season, which runs from April to November, while Ephren Barajos of United Farm Workers puts the figure closer to 50,000.

"Without a legal way to get a license, it's a lose-lose situation all the way around," Barajos says. "Workers are going to drive, with or without a license. To get to work on time, do shopping, get kids to schools and doctors, they need to drive. And they're doing it. None of us want to get involved in an accident, but it happens, and when it does and the other person is uninsured, then we're all in trouble. Repealing SB 60 was a bad move on the new governor's part."

Doug Keegan at the Santa Cruz County Citizenship project says that many of his clients were gearing up to get licenses come Jan. 1, and were very disappointed when Schwarzenegger repealed SB 60.

"Recognizing that 5 to 10 percent of the county is undocumented, and it's anyone's guess how many of them are actually on the road, most people I talked to wanted to get their license, wanted to be insured, and wanted to be protected," says Keegan. "In other words, they don't want to be a liability, a menace. Even in terms of a nonfatal collision, you want the other party to be insured for their sake, as well as yours. Uninsured drivers means higher premiums for the rest of us--and these people want to contribute."

Monterey CHP officer Richard Richards says that if people get caught driving without insurance, their car gets impounded for 30 days, and they're issued a citation, the fine for which is between $700 and $800.

"If we stop them, we ask for proof of insurance and license, but we don't ask for immigration status, because we don't have the resources to track that, and it's a federal issue, anyway," he explains.

And a local deputy who prefers to remain unidentified says that there is probably a low percentage of accidents involving undocumented aliens, "because people driving illegally, without insurance and licenses, tend to drive very cautiously because they don't want to get pulled over. But if alcohol is involved, then that changes everything because alcohol tends to impair judgment."

He also thinks that even if there was a law allowing everyone to get a license and insurance, not everyone would.

"The whole point of not getting a license, and of not getting insurance, is to avoid the costs involved in so doing. And if undocumented workers do get involved in an accident, they tend to run away out of fear. Even if we catch them, often times they are released after a preliminary hearing, at which point they run back to Mexico. It's more an economic than an ethnic problem. If you are a poor undocumented worker making more money than you could in Mexico, and sending most of it home, you don't want to incur the costs of getting a license, of getting insurance--or of being held responsible in the event of drunken driving."

Meanwhile, at the request of Metro Santa Cruz, Colin Jones of Caltrans' Public Affairs ran a search on his accident database to see if there's a higher than normal rate of accidents on the stretch of highway where Berridge died.

His search show that 50 accidents occurred there between April 1, 2000, and March 31, 2003--one fatal, 15 involving injuries, 41 multivehicular, two in wet conditions and 10 at night or in the dark--rates he says are a little below average in terms of fatalities and a little above in terms of total accident rates.

"Eighty percent of accidents are caused by driver error, be it excessive speed, inattention or driving under the influence," says Jones, "all of which can be exacerbated by a two lane highway, foggy conditions--and the fact that a driver may not be trained to drive on our roads."

Asked for his views on SB 60, all Monterey DA Steve Somers will say is that he'd rather see all drivers have licenses and be trained to know the law. As for Luna's legal status, he says he's been led to believe that she's not legally here, but that his office doesn't deal with immigration issues directly.

New Year, New Direction

Back in court, a week after New Year's Day, a court interpreter is summoned to help Luna enter a plea of not guilty, a plea that seems likely to be changed yet again two weeks later, according to Celera, who, having reviewed the evidence more thoroughly, is now considering settling with the DA--a move that leaves both the Berridge and the Luna families in an uneasy emotional limbo.

The Berridge family's biggest fear is that Luna will be released in relatively short order, while workers with the Monterey Peninsula Unified School District Infant program fret that Luna's daughter Kelly, who has an as-yet-unassessed genetic syndrome, won't get vital therapy as long as her mother is in jail or prison, or worse, if she is deported.

Meanwhile, Sen. Cedillo's chief of staff, Dan Savage, says an idea is being floated in Sacramento to offer undocumented workers the ability to purchase low-cost insurance from the California Assigned Risk Pool, a program that's administered by the California Deptartment of Insurance. It's an idea he hopes will breathe new life into the issue of driver's licenses for undocumented workers.

In an email that Berridge's fiancee sent out shortly after the accident, she recalled how David would always say to her: "Try and make each day better than the last."

David Berridge did not leave home that morning in October thinking it would be his last day. His loss was tragic and irreversible. But what if, in death, he becomes the poster boy for the pressing need for a law that could help prevent more tragedies like his from occurring?

In the meantime, Kirkeby confides that though she's never been known as a bookworm, she's already read 20 grief books and joined a grief counseling group--just to keep her going.

"I thought I was OK, but I couldn't get past my name," she confides about her first session. "I'm the newest in group. The grief keeps blindsiding me--like a car coming out of fog."

[ Santa Cruz | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

Cruel Twist of Fate: David Berridge once described a day spent riding his Harley as a perfect day. He was killed by an undocumented driver while riding this bike from Santa Cruz to Monterey last October.

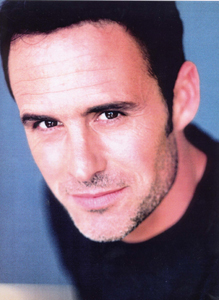

Model Citizen: The 44-year-old Berridge was a world traveled model who had been a motorcyling enthusiast for years.

The Mourning After: Berridge's widow says she's read 20 books on grief and loss, and joined a grief-counseling group, since the accident.

From the February 4-11, 2004 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.