![[Metroactive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

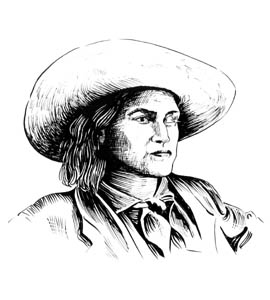

Nobody knows if she really was the first woman voter in California. Nobody knows why she spent her life dressing as a man. But the story of Soquel icon Charley Parkhurst turns the legend of the Wild West upside down.

By Daniel M. Hall

For several decades in the 1800s, stagecoaches were the main mode of transportation for people, baggage and mail in Northern California. And one of the best-known stagecoach drivers in the 1850s and 1860s was Charley Parkhurst.

Parkhurst drove sagecoaches over areas that are now largely dominated by freeways, houses and malls, routes that included Mariposa to Stockton, San Francisco to San Jose, San Jose to San Juan to Watsonville, and a lot of runs between Santa Cruz and Watsonville.

Driving a stagecoach took a lot of skill and courage, as drivers never knew what kind of situation--from holdups to incredibly hazardous conditions--they might have to deal with. Parkhurst had a reputation for being able to deal with whatever came along, and was known as one of the fastest and safest stagecoach drivers of the time.

Of course, there were many other competent stagecoach drivers. So what was the big deal about Parkhurst?

The big deal was that Charley Parkhurst was a woman. For most of her life, however, she disguised herself as a man, and both her unusual life as a cross-dressing stagecoach driver and her status as a registered voter in Santa Cruz County have made her a figure of local legend. There has been controversy over the years over whether Parkhurst ever actually voted, which would have made her one of the country's first woman voters, since national women's suffrage would not be won in the United States until 1920. Even New Zealand, the first country in the entire world to grant women the right to vote, did not do so until 1893.

According to the records of her former employer, Wells Fargo, Parkhurst "was small (only about 5' 6"), slim and wiry, with alert gray eyes. Apparently shy, Parkhurst never volunteered information about himself. Not an uncommon trait in those days. When he did speak, it was in an oddly sharp, high-pitched voice." In some older accounts of Parkhurst, her first name is given the masculine spelling "Charlie." On her tombstone and in her obituary, it is spelled "Charley."

Clothes Make the Man

Interestingly, in the 1800s many men wore beards and mustaches. Despite not having either, Parkhurst was able to pass as a man. No doubt it helped that no one at that time could envision a woman making a career of driving a stagecoach with teams of four or six horses.

Still, Parkhurst did her part with some creative dressing. She wore pleated shirts held in by a wide leather belt, blue jeans, a wide-brimmed hat and usually buckskin gloves--probably to hide her small hands.

She was handy with a gun and excellent with a whip, and could and would fight. In addition, Parkhurst was well known for her profanity. She liked to drink, chew tobacco and smoke cigars. (It wasn't all hard livin'--she was also known to be kind and very charitable to those in need.)

All that drinking with the boys threatened to loosen her lips, and on one occasion she let her secret slip, according to The Coachman Was a Lady, written by Mabel Rowe Curtis and published in 1959 by the Pajaro Valley Historical Society. At that time, she was staying with a family that had a house near Watsonville, and when Charley returned there drunk, the mother told her 14-year-old son to take the man to his room. Shortly thereafter, the boy ran to his mother and said, "Ma, Charley ain't no man--he's a woman." Still, according to Curtis, "Those good people, sensing Charley's humiliation if confronted with the fact that he was unmasked, never mentioned it to a soul until after Charley's death."

And, for the most part, it seems, neither did Parkhurst. What inspired this lifelong deception? The answers can only be guessed at based on a variety of information about her. She reportedly was born as Charlene Parkhurst in 1812 in New Hampshire. Not much is known about her life as a child or teenager, except that for a while she was likely raised in an orphanage, possibly in New Hampshire or Massachusetts. In Curtis' report on Parkhurst, she speculates: "It was an institution for girls and boys, else where would Charley find the clothes for the escape? Also, we assume girls' hair was cut short like the boys' for easier handling, so the disguise was complete."

During her time at the orphanage, she may have developed a fondness for horses. Whether she was permitted to leave the orphanage or escaped from it is not known, but shortly after leaving, she applied for a job at a livery stable in Worcester, Mass. (about 30 miles west of Boston), owned by Ebenezer Balch. Although historical records don't indicate if Balch knew for sure what gender Parkhurst was, he recognized that she was good at handling horses and trained her to drive coaches and carriages with teams of two, four and six horses. It's possible that she simply realized that she would have to disguise herself as a man the rest of her life if she wanted to stay in the stagecoach business, and this may be when she decided to do so.

When Balch moved to the growing city of Providence, R.I., about 30 miles south of Worcester, in the early 1840s. Parkhurst went with him and became a popular driver for people traveling around the city and the surrounding countryside.

Go West, Young Apparent Man

No historical documents indicate that Parkhurst knew how to read. But she still must have heard plenty about the discovery of gold in California in the late 1840s and the rush by people all over the world to go there to find their fortune. The gold rush also meant a need for more stagecoach drivers out West, so in 1851, Parkhurst went to California.

Her hopes were momentarily dashed when she arrived in San Francisco to find there were a lot of unemployed miners who were trying to find work as stagecoach drivers. But with her drive, talent and experience, she had no problem getting a job right away.

Parkhurst quickly found that driving a stagecoach in the Wild West could be a hazardous proposition indeed. First, there were the bandits. The first time that Parkhurst was held up, she was caught completely off-guard. The stagecoach had just rounded a curve when a masked man with a gun appeared and demanded that she throw down a box that could have contained gold and other valuable items.

She did, but after that incident, Parkhurst decided to become proficient with a .44 pistol and have it near or on her while she worked. So when the next robbery attempt occurred, Parkhurst quickly grabbed her gun and shot the robber dead.

Then there were hazardous road conditions. On one trip, Charley raced the stagecoach onto a rickety bridge spanning a storm-swollen river, and then looked back to see the section she had just crossed being washed away. She pushed her horses to get the stagecoach to land--just before the entire bridge collapsed.

Last but not least, of course, she had to deal with flirtatious women who assumed Charley was a man.

Although Parkhurst was fond of horses, they didn't necessarily treat her in the same way. While shoeing a horse, she was kicked in the left eye. She lost sight in that eye and thereafter wore a patch over it. After that, many people referred to her as One-Eyed Charley. On another occasion, her team veered off a road so suddenly that she was thrown from the coach. Hanging onto the reins, she was dragged along until she managed to turn the runaway team into some bushes and gain better control of them. The appreciative passengers took up a collection and gave her $20.

Considering all of this, it's not surprising that after several decades of stagecoach driving and growing rheumatism in her hands, Parkhurst decided to quit that work in the late 1860s.

Rocking the Vote

About the same time--1867 to be exact--Parkhurst, while living in Soquel, registered to vote in the election of 1868, which featured presidential candidates Horatio Seymour of New York and Civil War Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

While there is a document proving Charley's registration on file, unfortunately no evidence has surfaced over the years to indicate that she actually voted in the 1868 election, which would have been a significant event at that place and at that time. On her tombstone in a Watsonville cemetery, a plaque declares that Parkhurst was the first woman to vote in the United States. But according to a spokesperson for the Pajaro Valley Historical Society, which has lots of information about Parkhurst, that is no longer a correct claim. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, a few states allowed women to vote. Women across the U.S., however, were generally not allowed to vote until 1920 when the 19th amendment to the Constitution was enacted.

The legend that Parkhurst was the first women to vote in the U.S., however, led to a plaque being placed on a building in Soquel that said, "On this site on November 3, 1868 was cast the first vote by a woman in California--a ballot by Charlotte 'Charley' Parkhurst, who disguised herself as man."

It is possible that she did vote when no other voters were around in the small village of Soquel to see her in the voting area. And perhaps documents used to record who voted in the town on November 3, 1868, were lost or discarded and any official who was there had passed away before Charley died or moved away from Soquel after 1868. If Parkhurst actually did vote in the election, she kept it a secret along with her gender.

After she retired from stagecoach driving, Parkhurst pursued several other occupations. She ran a station between Watsonville and Santa Cruz for changing stagecoach horses. Later, she worked at lumbering and cattle ranching, and then raised chickens near Aptos. According to a letter written by George Harmon (whose mother and father were close friends with Parkhurst, published in the March 13, 1930, issue of the Watsonville Register-Pajaronian, Parkhurst got permission from "his" father to move into a small house near the Harmons' ranch house (situated about six miles from Watsonville) around 1876. "During the early part of 1879, she complained of a sore throat and swelling on the side of her tongue. The trouble proved to be cancer, which was the cause of her death. She died on December 18, 1879," Harmon wrote.

Harmon said a long-time acquaintance of Parkhurst was with her when she died, Frank Woodward. He also says in the letter that Parkhurst told him that "she had something to tell" Harmon's father before she died, "but there was no hurry about it." Perhaps she wanted to tell him the secrets of her life.

After she died, a doctor and maybe an undertaker discovered that Parkhurst was a rather well-endowed woman. That was a real surprise to most everyone, especially to Frank Woodward. He reportedly reacted with a lot of profanity.

The revelation that Charley was a woman generated a lot of newspaper stories, some of which didn't treat her very nicely.

For example, the San Francisco Call remarked, "No doubt he was not like other men, indeed, it was generally said among his acquaintances that he was a hermaphrodite" and "the discoveries of the successful concealment for protracted periods of the female sex are not infrequent."

Throughout the years, there has been speculation that the doctor or undertaker may have revealed that there was evidence that Parkhurst had given birth. Adding fuel to that speculation were reports that a baby's shoes were found among Charley's possessions after she died.

This is only one of the many mysteries that still shroud the life of Charley Parkhurst, a woman with a lot of secrets both then and now.

[ Santa Cruz | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Buy the historical novel 'Riding Freedom,' based on the life of Charley Parkhurst, written by Pam Munoz Ryan and illustrated by Brian Selznick.

![]()

The Strange Life and Times of Charley Parkhurst

From the March 5-12, 2003 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.