![[Metroactive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

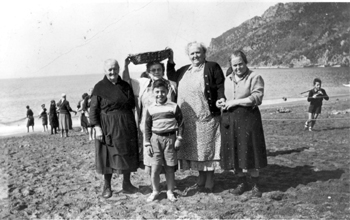

Mary Carniglia (left) with her mother and sisters.

Big Mama

'Mama Mary' Pesto Feed honors pioneering Italian immigrant Mary Carniglia, who made a huge mark on Santa Cruz

By Sarah Phelan

Known as "Mama Mary" within the Santa Cruz Genovese fishing colony, this legendary matriarch was the first woman to open a business on the wharf, the first Italian woman in town with bilingual skills and an English education--and the first to spring to the defense of her community in 1942, when Santa Cruz west of the highway was declared an area from which Italian (as well as German and Japanese) aliens had to be removed in the wake of 1941's Pearl Harbor bombing.

Yes, there are plenty of reasons to honor and remember Mary Carniglia (1898-1985), including the fact that her birthplace, Riva Trigoso-Sestri Levante, is now Santa Cruz's sister city in Italy, an idea originally proposed by, you guessed it, Mama Mary herself.

"Though I'm not from Genoa, I feel connected to the maritime immigrant culture," says Cristina Polesel, a Venetian immigrant, who is currently organizing the "Mama Mary" Pesto Feed, which coincides conveniently with International Women's Day, March 8.

"When I first got here, I got the same impression as Mary Carniglia must have. Santa Cruz is very similar to many towns of the Genova region on the Italian coast, only the Genovese architecture is hundreds of years old. But the weather, the laid-back attitude, the feeling that the quality of your life is as important as your career, these are all very familiar," says Polesel, who arrived here six years ago as a grad student at UCSC, and experienced serious culture shock.

"I think Mary and all the other Italian immigrants went through a similar experience--only harder," Polesel says.

No kidding. Carniglia's family's move here from San Francisco was triggered by the Great Earthquake of 1906. Before that, Mary's father would sail to Santa Cruz to fish for salmon, and bring the family here for a vacation in the summer. So, when the earthquake hit, followed by a huge fire, Mary's father picked up Italian families in his boat and brought them to the shelter of the Santa Cruz wharf.

"As Mary once said, 'There was the heart and love to do that.' Now you don't get that sense anymore, but I relate to her understanding of the family as the first institution to be protected, that sense that if you protect the family, you protect the culture," says Polesel, adding that Mary's mother wanted to return to Italy in the wake of the earthquake

"She cried when Mary's dad said that if she did, he would keep the three girls, including Mary, here. So, in the end, the whole family stayed."

The good news for Mary was that she got to go to school, and thus learned English, which allowed her to help the Italian community understand everything from citizenship paperwork to doctors' instructions during childbirth.

The bad news was that she became a loner and isolated at school.

"The kids at school teased her for the old-fashioned way she dressed, not to mention her mother, who wore black all the time after Mary's father died, and looked more like a nun," says Polesel. "So, Mary went through a hard time. But she was a great networker, a strong woman. If someone bit her, she bit back, and not just to protect herself, but the whole colony, which is why she got the respect she deserved."

Class Consciousness

Polesel says one thing she really likes about Santa Cruz compared to Italy is that you don't need to worry about your appearance, but things weren't yet as casual in Mary's time.

"In Italy, you must always be dressed up, which I can't stand," says Polesel. "Well, Mary went through the same thing, only in reverse. Hers was a fishing family in which there were no mirrors in the house and vanity was not a good thing, but when she went to school here, she felt left out because everyone was dressed up in nice clothes."

On the plus side--sort of--her lack of cool clothes wasn't an issue when it came to dating, since Carniglia's marriage was arranged by her dad.

"If you look at societies which still do that, you see that arranged marriages are typically marriages of interest," says Polesel. "But Mary's father didn't arrange for her to marry a wealthy guy, but someone who would keep the family together--Marco Carniglia, an Italian youth, whose grandfather transported wine and cheese in the Mediterranean.

According to historical records, Mary was told of this arrangement when her father called her to his sick bed, and told her that Marco had asked for her hand. Said Mary's weak and dying dad, "You should always go to school and when you have finished, you will marry. This young man will take care of you and your two sisters. This is a command. Between all the young men that have asked to come to ask for you in marriage, I have chosen him because I knew his parents. This way your mother and I will die happy."

Nice.

Asked if she could handle an arranged marriage herself, Polesel says, 'No, I think it would be too hard, and besides I can take care of myself. But Mary's acceptance of that came, I think, from love at all cost for your family, and Marco was a sweet guy, who took care of her dad like a son. Besides, Mary didn't have any options, and she understood that sometimes to survive, you have to be strict. She wasn't a rebel child, but she did face the hardships in her life with a great attitude."

That attitude clearly included a natural-born entrepreneurial spirit. In between giving birth to five sons and two daughters, Carniglia did the books for the fishing business on the Santa Cruz wharf, and in 1940 opened the Miramar Restaurant, a move that made her the first bilingual businesswoman on the wharf. She sold the Miramar after World War II and bought the Riviera Hotel (today's Positively Front Street), where she gave away postcards with ravioli dinners.

But running a business wasn't her only focus. In 1940, Carniglia became a citizen, a factor that helped her assume a diplomatic role in 1942, when the U.S. government ordered the Italian fishing colony to move away from the ocean and prohibited them from fishing.

As local historian Geoffrey Dunn, who just happens to be Carniglia's great-nephew, notes, "The day following FDR's declaration of war, a dozen nationals were no longer allowed to take their boats out to sea."

The restricted fishermen included Stefano Ghio, Giovanni Olivieri, Batista and Frank Bregante, Serafino Canepa, Niccolo Bassano, Giacomo Stagnaro, Agostino Oliveri, Fortunado Zolezzi, Johnnie Stellato, Johnnie Cecchini--and Marco Carniglia. All these fishermen had to move out of their homes in lower Bay Street and in the flats east of Neary Lagoon and resettle on Berkshire Street.

Mary, whose eldest son John was also serving in the Navy, immediately jumped into the fray, writing letters to government officials and giving lengthy interviews to the Santa Cruz Sentinel.

Eerily foreshadowing 2003, in which men of Arab descent are under suspicion of having terrorist sympathies, Mama Mary said, 61 years ago no less, "My people are proud to be in America. Their coming here gave her a taste of paradise. They aren't disloyal. If the government can show disloyalty, then they should be punished. I wouldn't fight for them if I thought they weren't loyal, but they are."

She also fought racketeering by local landlords, whom she accused of taking advantage of the relocation controversy, by hiking rents and refusing to rent to families with children. But though she called for an emergency rent-control measure, such a law was never passed.

However, she did succeed in getting four Italian men freed, after they were jailed for breaking the engines of their ship, when it was impounded in North Carolina shortly before World War II. For her efforts, the Italian government presented her with Italy's international Golden Leaf in 1971, in recognition of her outstanding community service.

"She was very advanced woman for her time," says Polesel.

Reflections on her fierce love for her community and family, by someone who was part of both

By Geoffrey Dunn

If ever there was a woman in Santa Cruz who both defined and embraced the spirit of this community in the 20th Century, it was Maria Bregante Carniglia, my great-aunt. She was widely known as "Mama Mary," but I always called her "Lala," which, in the Italian dialect of Genovese, was the affectionate term for one's aunt or great-aunt.

She was a kind and gentle woman, dignified and intelligent, fiercely loyal to her family and to the wider Italian fishing community that had immigrated to Santa Cruz from Riva Trigoso, Italy, at the turn of the century. She was also incredibly strong and fierce, and, when someone crossed her, she could be tough as nails.

As a kid growing up in Santa Cruz's West Side Italian community--known as the Barranca, on the lower end of Bay Street--I found Mary to be something of an imposing, no-nonsense figure, and my cousins and I steered clear of her garden and the family clothesline, lest we engage her wrath.

By the time I reached my early 20s, she had welcomed me into her home for late afternoon conversations over red wine, and I would leave her a few fillets of fresh fish following my daily stint on the cutting tables at the wharf. She was an amazing cook, ranking among the best in a neighborhood where gourmet food was the daily fare. I became a regular.

In the early 1980s, I conducted a 16-hour oral history of Mary for the California Italian Arts Organization. Mary was up in years at the time, and her memory was slipping, but the best moments in the interview invariably came when she would demand that I turn off the tape recorder and tell me stories about who was running rum during Prohibition, who sold drugs in Chinatown, and who was sleeping with whom and when. Nothing got by her. She was the matriarchal pulse of the waterfront.

In the film A Day on the Bay, produced in 1981 by Riccardo Gaudino and my longtime film partner Mark Schwartz, Mary told a story about being harassed about her Italian ancestry by one of her WASP classmates as a young student at Bay View Elementary School. She recounted the initial segment of the tale with all the piety of a good choir girl, then suddenly switched gears, and with the tenacity of a street urchin, recalled her triumph over her tormentor with the unforgettable line: "Ya thought you could beat a dago, didn't ya?"

During the Second World War, Mary's tenacity was put to the test.

As Gen. John L. DeWitt, commander of the U.S. Western Defense Command, began the process in early 1942 of relocating Italian fishermen from Santa Cruz inland of Highway 1, Mary, whose husband Marco was impacted by DeWitt's relocation orders, came to their defense.

She wrote letter after letter--to the newspapers, to elected officials, all the way to the White House. In a missive to the Santa Cruz Sentinel, written in January of 1942, she wrote passionately of the federal effort to relocate Italians along the Pacific Coast: "It hurts. My people have lived here in the same houses for three generations ... The fishing industry will be hit hard. Many of the boys have gone into the service; others are holding back now because if the fathers have to go, who will keep the families?"

That, in the end, was what Mary was all about--family and community. By Columbus Day of 1942, DeWitt's order to relocate West Coast Italians was rescinded by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt; the Italians were allowed to return to their homes and to their boats. I have little doubt that in the back of Mary's mind she was thinking: "Ya thought you could beat a dago, didn't ya?"*

[ Santa Cruz | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photo Courtesy of Geoffrey Dunn

The "Mama Mary" Pesto Feed takes place in "Fisherman's Alley" on Bay and Gharkey streets, behind Lighthouse Avenue, Santa Cruz, featuring all-you-can-eat pesto, Genovese pasta, calamari and salad. Tickets are $12 for adults, $6 for kids 8-12, free for kids 8 and under. Feed times: 12:15pm, 1pm, 2pm, and 4:30pm. All proceeds go to the "A Day on the Bay" fund for library resources and Youth in the Arts. Santa Cruz High teen artists will paint Riva Trigoso street scenes. For tickets, reservations and rainy day location call 454.1161.

Memories of Mama Mary

Geoffrey Dunn, a fourth-generation member of the Santa Cruz Italian fishing community, is the author of 'Santa Cruz Is in the Heart.'

From the March 5-12, 2003 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.