![[MetroActive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

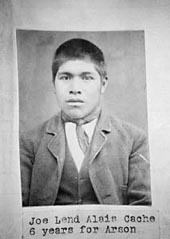

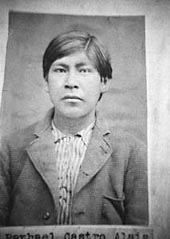

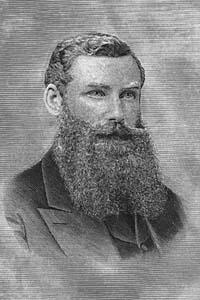

The Catcher and The Shortstop: Joe Lend, alias Cache, and Raphael Castro, alias Tahoe.

Fires of Fate

A century ago, two Mission Hill Indians named Tahoe and Cache stood trial for barn-burning. Were they victims, rebels or vandals?

Their case, rescued from archives, transcripts and newspaper stories, sheds new light on the complex role of Native Americans and other 'outsiders' in late 19th-century Santa Cruz

By Geoffrey Dunn

A SERIES OF SUSPICIOUS fires erupted throughout Santa Cruz and the surrounding vicinity in 1884. In early December of that year, flames engulfed a barn owned by prominent Santa Cruz entrepreneur and politician William H. Bias, reaching into the cold late-autumn night. Santa Cruz's crack fire-hose team, led by Samuel Cowell, the son of local industrialist Henry Cowell, responded to the call, only to arrive too late. The Bias barn lay in ashes.

It was the sixth suspicious fire in recent memory. Deputy Sheriff Henoc "Noch" Alzina, a stalwart of local law enforcement, noticed that two young California Indian men--Joe Lend and Raphael Castro, known throughout the community by the nicknames "Cache" and "Tahoe"--had been the first observers at several of the fires and, according to the Santa Cruz Daily Sentinel, "were not inclined to assist in extinguishing the flames."

At 2am, in the dark morning hours of Friday, Dec. 5, Alzina, by his own account, arrested Lend as he was heading into the train tunnel beneath Mission Hill. Castro was arrested at his home.

Only a few days later, Lend's "confession" was printed in the Sentinel under headlines reading, "The Barn Burners: Two Indian Boys Arrested for Arson--One Confesses, the Other Denies."

The accompanying article indicated that the two "boys" had been brought before Judge Edgar Spalsbury in a preliminary hearing and that they "did not want an attorney."

Lend's testimony was published in full detail:

District Attorney: Who set Towne's barn afire?

Lend: Me and the other fellar. We had nothing against Mr. Towne, we like him.

District Attorney: Why did you do it?

Lend: Just for fun. We was tight and wanted to have a fire ...

District Attorney: Did you use coal oil to do it?

Lend: Yes, somethin' like that.

Lend, according to the testimony that was printed, went on to accept responsibility for several other arsons, but not all. There were some, he said, of which he had no knowledge. Castro denied any involvement. He claimed to have been in bed during the Bias fire. He said Lend had lit the others, including one at the house of Alfred Imus, but that the fire had gone out on its own.

Deputy Sheriff Alzina disputed Castro's testimony. He said that both Lend and Castro had confessed to him immediately upon their arrest. According to Alzina, Lend said he was unconcerned about his fate, as he "had nobody to care for him."

The judge set bail at $2,000 apiece--an enormous sum in those days. Lend and Castro awaited their justice in the old jail, near the Mission Plaza. A dog that had befriended the young men waited patiently for their release at the gate.

Photo courtesy of the Geoffrey Dunn collection

Old Santa Cruz

DURING THE EARLY 1950s, Ernest Otto, the dean of Santa Cruz journalists, who had been born at his family home on the corner of Church and Cedar streets in 1871, recalled the saga of Lend and Castro in his "Old Santa Cruz" history columns that appeared regularly in the Sentinel.

Otto had been a 13-year-old boy at the time of Lend and Castro's arrest, and his recollections indicate that he was intimately aware of their circumstances. It is through his eyes and his childhood experiences that we have any sense at all of the lives of the two young men.

Referring to them solely by their nicknames, Cache and Tahoe, Otto described them as being "known and liked by everyone" and as "kind and gentle." He recalled that they "knew where fish and game could be found and had friends ready to buy their catches." He described them as "inveterate bird-egg collectors" who could always locate nests, even those "of the rarest birds in this section."

Otto identified both Cache and Tahoe as "two of the best" players on the Santa Cruz Powder Works baseball team that played its games on the present site of Pogonip.

"Cache was a catcher, and Tahoe a shortstop so fast on his feet he could almost keep up with the moving ball," Otto recalled. In another column on the same theme, he described Tahoe as "one of the very best shortstops in the city and [he] moved like lightning when running the bases."

The two young men, according to Otto, were the sons "of the last surviving Indians of the mission," a woman identified by Otto as "Maria" and her sister, whom he did not identify by name. According to Otto's accounts, the two women "always were seen together in their plain skirts and with black shawls over their heads and wrapped around their shoulders. They took in washing and had many customers."

In one column, Otto identified them as living on Potrero Street; in another, on Evergreen. Both streets were (and are to this day) located on the back slopes of Mission Hill in what was then known as the Potrero--today divided by Highway One, with Harvey West Park to the west and the Sash Mill compound to the east--the common pasture lands deeded to local native peoples following the decline of Mission Santa Cruz.

'Lo, the Poor Indian'

IF LEND AND CASTRO were 19 at the time of their arrest, that would have placed their births in 1865. Baptismal records at Mission Santa Cruz indicate a number of baptized "indios" that year. One, in particular, registers the baptism of a boy named José, born illegitimately ("natural") to a mother named María and a father named Jesús y María on June 18. That is likely Joe Lend. County records indicate that the two parents were later married.

The following year, in an article titled "Lo! The Poor Indian," the Sentinel reported that "Jose [sic] Maria and Alajon, two Indians of the Santa Cruz tribe," were arrested for assault and carrying concealed weapons.

"When the Santa Cruz Mission was established," the article continued, "the tribes of Indians at Aptos, Soquel and Santa Cruz numbered nearly 3,000. All are now scattered or have passed away; their tribal character has become extinct--except about forty, who have their houses on the Potrero, within the limits of our incorporation. These few keep up their tribal distinctions."

The article went on to describe in considerable detail how the Indian lands were being usurped by the growing number of both Yankee and European immigrants arriving in Santa Cruz and how that contributed to the Indians' arrests.

Taking a surprisingly sympathetic, albeit stereotypical, stance, the article declared:

Would it not be well for the citizens of Santa Cruz to now determine that the Potrero ... shall be forever set apart to those Indians and their children, and that no vandal shall ever despoil them of what the good priest gave them for services rendered.

Speaking directly of the two California Indian men charged with the crimes, the article concluded: "The poor fellows are industrious, earn their own living, are a tax upon no person, and are quiet and inoffensive. Then, for humanity's sake, if not for the sake of law and justice, let us protect them in what is their right, and punish those who do them this great injury."

Sons of the Forest

TWO DECADES LATER, Joe Lend and Raphael Castro would receive no such sympathy from the local daily. Immediately after they were arrested, the Sentinel--then controlled by Duncan McPherson--fanned the flames of public sentiment against them.

Under a headline proclaiming "Bad 'Injuns,' " the daily railed, "Now that the two Indians are in a safe place, where they cannot indulge in their propensity to 'have a little fun,' by setting barns and houses on fire for the 'pleasure of seeing the firemen run,' the owners of property can sleep tranquilly."

The paper referred to the two men derisively as "illiterate and drunken," "sons of the forest," "childlike and bland" and "warriors," and to Indian women as "copper-colored squaws."

"The Indian nature," the Sentinel opined, "does not understand the duty that is due to civilized society, and it can not fathom the reasons why any respect should be paid to law and order."

The only redeeming description was offered by Mrs. P.B. Fagen, a member of Santa Cruz's crusty elite, for whom Lend had worked as a gardener and buggy driver. She described "Cache" as "faithful and industrious," as well as "honest." She attributed his errant behavior to "strong drink" and likened his disposition to that of a child.

Her empathy did nothing to stem the tide.

Little more than two weeks after they were arrested--without ever having received legal representation--Lend and Castro were sentenced to six years each at San Quentin Prison by presiding Judge James H. Logan.

According to the Sentinel, "the two dusky 'braves' ... received their sentences with a sardonic grin, and with as much nonchalance as if they were going to a place where they would be permitted to set fire to a barn before each meal. Cache and Tahoe calmly smoked cigarettes on the way to jail and seemed to be contented and happy."

On Christmas Eve 1884--19 days following their arrest--the Sentinel reported that "the Indian firebugs were taken to their future home at San Quentin. ... They regarded their removal to prison more in the light of a 'picnic' than a punishment. Whether they will learn different, time alone will tell."

The Santa Cruz Alerts Fire-Hose Team: Samuel Cowell is the second firefighter from the left.

Surviving Statehood

IN THE INTRODUCTION to her important work Conquests and Historical Identities in California: 1769-1936, UCSC associate professor of history Lisbeth Haas recounts the story of Modesta Avila, a young Californio woman from San Juan Capistrano, who in 1889 nailed a fence post to a railroad track that ran by her home, demanding payment from the Santa Fe Railroad Company for the right of passage.

Avila, born just two years later than Lend and Castro into a similar postcolonial community, stuck a piece of paper to the fence post that read: "This land belongs to me. And if the railroad wants to run here, they will have to pay me ten thousand dollars." She, too, was sent to San Quentin for her bold transgression against property rights, receiving a sentence of three years.

Were the fires of Joe Lend and Raphael Castro, like Modesta Avila's defiant declaration, also acts of rebellion against a social order bent on conquest and domination? Or were they simply the frivolous acts of "childlike" and "drunken Indians," as they were attributed in the press and in the courts?

When reconstructing the past it is important not to read into the historical record more than is there; speculation, particularly in history, can be deadly.

At the same time, it's equally important not to accept carte blanche reports or interpretations of historical events, particularly when they are those of people in power who have a stake in the way they are presented. We must look back at the past with fresh eyes and reconstruct it for ourselves.

Contrary to widespread perception, California's native population--numbering approximately 300,000 prior to the arrival of Franciscan missionaries in 1769--was not "wiped out" by the missions. Many survived well beyond statehood in 1850. There were concentrated military and vigilante campaigns directed at California's native peoples throughout the state well into the 1870s, culminating with the U.S. Army campaign against Kintpuash (Captain Jack) of the Modoc tribe that led to his capture and hanging in 1873.

It was more than the introduction of European diseases that decimated the native peoples of California; there was a systemic pattern of state-sanctioned genocide.

Nor were the California Indians passive in the face of colonial and military aggression. Rebellion was commonplace throughout the mission era and early statehood, and Santa Cruz, in particular, had a sustained legacy of resistance. As early as 1793, a tribal leader named Charquin, head of a Quirosote community near Año Nuevo on the North Coast that had long resisted the intrusion of the missions in San Francisco, Santa Clara and, finally, Santa Cruz, led an assault on the local mission compound.

Two decades later, members of regional Ohlone tribes confined at Mission Santa Cruz strangled Father Andres Quintana, a mission priest known for his use of metal-tipped whips and thumb screws on native peoples. His assailants also crushed his testicles.

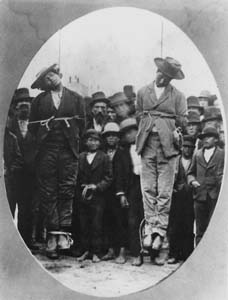

By the time Lend and Castro lit the fires, the free-flowing lands of their childhoods in the Potrero had been significantly diminished. Laws had been passed severely restricting their hunting and fishing rights. They had witnessed first-hand lynchings and other forms of violence directed at native peoples. And they had been systematically excluded from the emerging political and economic order.

The barns that they burnt--in particular the Bias barn that had been built on Potrero lands--were symbols of that encroachment and subordination. Given both this legacy and these motivating factors, is it really all that difficult to conceive that the fires lit by Lend and Castro were, at least in some elemental aspects, acts of open rebellion?

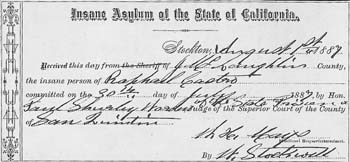

Final Outcome: Raphael Castro's commitment papers to the Stockton Insane Asylum.

On the Margins

IT IS ALSO IMPORTANT to place the story of Lend and Castro in a larger historical context. It was not simply an anecdotal local event, as Otto and many subsequent historians have portrayed it, but part of a long-term institutionalized assault on local peoples who were identified as outside the Santa Cruz mainstream.

The second half of the 19th century in California, as Haas argues, was a period of conquest and the subordination of ethnic identities in local communities. Santa Cruz was especially virulent in this regard.

Any ethnic group that did not fit into the emerging Protestant and Northern European power structure in Santa Cruz was systematically marginalized and designated as "other." This included not only California Indians, but Mexicans, Californios, African Americans, Chinese, Southern Europeans (most notably Italians) and Irish Catholics.

Almost from the moment that Santa Cruz County was established in 1850, Californios--natives of Spanish, Mexican, Indian or mixed heritage--were targeted. Many Californios lost their land titles through corrupt attorneys and legal proceedings.

Lynchings were also commonplace. As early as 1851, vigilantes pulled Mariano Hernandez from the local jail and hanged him; many more were to follow. The last Californio lynching locally occurred in May 1877, when Francisco Arias and José Chamales, both suspected of murder, were hanged from the Water Street bridge. The local legal structure, as well as the Sentinel, condoned the lynchings.

The immediate years before Lend and Castro were sent to prison also saw the uprising of an anti-Chinese movement that would consume the local community for the better part of a decade. Laws were passed that directly impacted local Chinese laundry men and vegetable growers. In 1882, just two years before Lend and Castro were sentenced to prison, Santa Cruz County residents voted 2,540 to 4 to oppose further Chinese immigration to the U.S.

The same Duncan McPherson who would refer to Lend and Castro as "bad injuns" and "dusky braves" had only five years earlier referred to the Chinese as "half-human, half-devil, rat-eating, rag-wearing, law-ignoring, Christian civilization-hating, opium-smoking, labor-degrading, entrail-sucking Celestials."

The subjugation of ethnic identity was so profound that, by the end of the century, Joséfa Perez Soto, a member of one of Santa Cruz's noblest Spanish families during the Mission era, would be identified as an "old Indian" by people in the community.

Like the Salinas River to the south, whatever remnants there were of local California Indian society and culture were forced to run underground.

Photo courtesy of the Geoffrey Dunn collection

The Catcher and the Shortstop

AND WHAT OF Tahoe and Cache? Time, indeed, as the Sentinel editorialist portended, did spell out their fates, and in short order. San Quentin in the late 19th century--let alone today--was a bastion of brutality and disease. Thousands of prisoners during this era--many of them California Indians--died there, including Modesta Avila.

According to records obtained from the California Department of Corrections, on May 3, 1886, little more than 16 months after he arrived, Joe Lend died from "scrofula," more commonly known as tuberculosis of the lymph nodes. He was 20 years old. This former baseball catcher and egg hunter known as Cache was buried in a common grave for Indian prisoners.

A year after Lend's death, according to San Quentin records, Raphael Castro went "insane." The speedy shortstop known as Tahoe was sent to the Stockton Insane Asylum in August 1887. He died there a year later, at the age of 22.

His burial records have been lost.

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photos courtesy of the Special Collections, McHenry Library, UCSC

An excerpt from 'Santa Cruz Is in the Heart: Volume II'

Lend: I am 19 years old. Me and the other fellow [Castro] was on our way home near Kron's tannery, and the other fellow said he wanted to go back to get matches and see the fire boys run. ... We had no grudge against Mr. Bias.

Hanging at the Water Street Bridge, May 1877: Francisco Arias and José Chamales were lynched by an unidentified Santa Cruz mob. Lend and Castro would have been 11 or 12 at the time of the lynching.

Hanging at the Water Street Bridge, May 1877: Francisco Arias and José Chamales were lynched by an unidentified Santa Cruz mob. Lend and Castro would have been 11 or 12 at the time of the lynching.

Our Indians have not become extinct on account of losses in war, or pestilence, but the grasping avarice of the whites drove them from their lands and happy hunting grounds, and disheartened, they roam unguided through the land, and drop down and perish by the wayside, or become the victim of their white friends who sell them the Indian's curse--whiskey.

Photo courtesy of the Geoffrey Dunn collection

Photo courtesy of the California Department of Corrections

Duncan McPherson: His was the language of conquest and subordination.

Duncan McPherson: His was the language of conquest and subordination.

The author would like to thank Father Mike Marini and Phil Reader for their generous assistance in researching this article. Excerpted from Santa Cruz Is in the Heart: Volume II (forthcoming). Copyright ©2000 by the Capitola Book Company.

From the March 15-22, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.