![[Metroactive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Santa Cruz | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

The Revolution Will Not Be Verbalized

Best known as the man who brought hip-hop to Shakespeare, choreographer Rennie Harris takes evasive action in an interview about his newest multimedia work, 'Facing Mekka'

By Mike Connor

Artists ... they're a tricky lot. They go around creating all this stuff, and then sometimes they refuse to explain it. Like, has David Lynch ever sat down and explained what in the hell that nasty monster behind the dumpster in Mulholland Drive is all about? No. Why? Well, because it's not an artist's job to explain his art. Sometimes, the mysterious, unexplained midgets are just part of the fun.

Although he may not be quite as fun as an all-powerful midget, you could say that hip-hop choreographer Lorenzo "Rennie" Harris is a pioneer in choreography, even a hip-hop revolutionary. Call him a dancing guru spreading spiritual enlightenment and cross-cultural understanding in an urban idiom. Call him a pan-spiritual disciple of dramatic, high-flying ecstatic ritual dance, who uses movement as a metaphor for his conception of Mekka. Call him all this and more ... just don't expect him to agree with you.

The enormously talented director/choreographer is creative, challenging and even a bit tricky ... to interview. His newest work, Facing Mekka, presented April 14-15 by UCSC Arts and Lectures at the UCSC Theatre Arts Mainstage, is a multimedia work of impressive scope, employing 17 dancers, two DJs, live tablas, sitar, vocals that include a human beatbox, and ambient video projections.

But while it's easy to say what Facing Mekka is, Harris isn't one to be pinned down on what it's about. He won't spout off about the cultural significance of his work, or what his creative mission is. In particular, he has little time for questions laden with preconceptions of what his latest work is all about--even ones gleaned from his own website.

"A lot of times when I'm doing projects," he says with a tinge of noble exasperation, "people are picking my brain as to what it is that I'm doing or what it is I want to do, but the reality is that you never know what it is that you're doing. When you just get inspired to create something, it's not analyzed or broken down, and there's not a strategic plan."

Indeed, pushing forward without a plan seems to be Harris' modus operandi. By way of introduction, 37-year-old Harris grew up in Philadelphia and has been dancing professionally since he was in high school. After a lecturing and dance stint at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., he went on tour around the country and abroad with the "Fresh Festival," which included old-school hip-hop superstars Run DMC, the Fatboys, Kurtis Blow and Whodini. Damn, those were the days ... but oh, then he worked in New York for a while, before moving back to Philly, where he set up camp. In 1991, he was commissioned to create 45 minutes worth of theatrical dance pieces, thusly getting paid for doing what he loved to do.

Slowly but surely carving out a name for himself in the world of dance, Harris struck gold in 2000 with his breakthrough hip-hop opera, Rome and Jules. Inspired by West Side Story and Baz Luhrmann's strangely anachronistic Romeo + Juliet, Harris hip-hop-ified Shakespeare's classic, turning the Montagues and Capulets into B-boys and hip-hoppers. Powerful acting, incredibly graceful and acrobatic dancers and a bumpin' soundtrack earned the play widespread critical acclaim. While on tour in Europe, Harris had never heard of the Lawrence Olivier Award, but that didn't stop him from winning it anyway.

Harris and his company Puremovement may be one of the more successful hip-hop repertory acts, but he points out that they were by no means the first ones to bring hip-hop into the theater.

"Hip-hop was already in the theater in the '80s," Harris recalls. "It's just a matter of, again, when the media decides that it is going to put it in the foreground, or whether or not it's time for people to accept it. In the '80s in New York we were already doing hip-hop in theater, you know ... Stephanie Space, The Kitchen, PS122, they had already had it. It was a novelty then, I guess, so it didn't catch on. But then in Europe they've been doing hip-hop in theaters since the '80s, so for the most part, again, the American understanding of hip-hop and its history is a little ... behind."

Yo! Academia Raps

The new wave of academics revel in the way that hip-hop lends itself to postmodern philosophy. As the art of sampling and mixing continues to develop in hip-hop music, more and more artists contribute to the intertextual cross-referencing/pollination between genres and styles from all over the world. Luckily, we have people like dance critic/historian Suzanne Carbonneau to trace the roots of the styles we see in hip-hop dance today.

"Hip-hop," writes Carbonneau, "represents the confluence of at least five distinct cultures of the Black Atlantic that were vibrant in the South Bronx when hip-hop was gestating there in the 1970s: Afro-Barbadian, Afro-Jamaican, Afro-Cuban, Puerto Rican, and North American funk. As b-boying (which became popularly known as break dancing) was emerging on the East Coast, electric boogaloo and popping were coming out of Fresno and Los Angeles. All of these unique Diasporan cultures share African retentions that form the bones of hip-hop, just as they have provided the skeletal structures for all previous American vernacular styles."

Carbonneau sees significant influences from other cultures, as well. "With the popularity of Bruce Lee films in the '70s, the precision and dynamic movement of Asian martial arts were also absorbed, as well as, some have suggested, the floorwork of capoeira, the Angolan/Brazilian martial art form," she writes.

From his own experience, Harris can easily rattle off a list of the styles of dancing that people call "hip-hop," pointing out that it's much more than helicopters and head spins.

"A lot of people don't realize that there's a lot of styles of dance that fall under the umbrella of hip-hop," Harris says. "You know, you're talking about robot, popping, boogaloo, strutting, sagging, boogie. You're talking about flexing, house, trendy, vogue, second-line, Then you have B-boy, then you have hip-hop proper. So there's a lot of different styles that go under the umbrella of hip-hop, and a lot of times the public is only bombarded with the acrobatics of hip-hop, which is B-boying."

But while that's all well and good, Harris insists that his approach to choreography is more intuitive than academic.

"I use stuff that's in my consciousness," he says, "so if it is from Brazil, I'm not taking it specifically from Brazil. It may be from Brazil, or it may be a choice that one of the dancers might make, to move in that way. But most of the movement, I just created it, and of course whatever comes out is a reflection of my influences and the things I've been around, the things that I've seen. But it's not about me going to Africa and taking movement from Africans and saying 'OK, we'll put this in here.' But rather, how do I still get that same feel with the movement that I'm just going to create on the spot?"

With well-honed intuition and sensitivity, Harris is able to convey religious overtones through popping, a form of dancing that he sees as very internally therapeutic. Onstage, his involvement in the dance often verges on ritual, lapsing into theatrical meditations that, along with ethereal soundscapes, launch straight into the spiritual realm. He talks about being alive even to the current of air in the room, but stops short of calling it his own personal church.

"I don't want to say I'm spiritually minded, necessarily, but I've always been on the path of journeying, so to speak. Because really, it's not about other people, it's about me. It's about how I'm dealing with me, and so right now, this is my therapy, and if it relates to other people, then God bless, you know, that's cool, and if it helps them, that's fine, but right now that's what it's always been about, me trying to figure out where I'm going."

Not that he's taking all the credit, by any means. When asked where the "Mekka" in the title comes from, Harris points to his collaborators, and to Kenny Muhammad in particular. Dubbed "The Human Orchestra," Muhammad delivers snippets of Muslim prayer in the performance, along with his prodigious multi-instrumental human beatboxing skills. Musical composer and producer Darren Ross, who also composed the music for Rome and Jules, and has worked with everyone from fellow-Philly-natives the Roots and Bahamadia to P.M. Dawn and Doug E. Fresh, calls the overall sound "world hip-hop." Although Harris may have had some ideas of how he wanted the music to sound, he didn't necessarily articulate them to the rest of his crew, even if they tried to steer him in a more explicit direction.

Ross says he pulled in influences from all over. "I was listening to a lot of Muslim chants and all kinds of music, trying to make this cohesive world sound," he says. "You get African and Hindi music in there, and we do a Cuban-type piece, too. We even have Scottish pipes over African drums, fusing it all together, and to me it becomes really dope and creative. To me, that's what hip-hop is all about, putting everything together and fusing it all into one."

"Before hip-hop," Harris says, "it was rhythm and blues, it was rock, it was jazz, it was classical, it was whatever gave you that sense of freedom that you could just go ahead and do your thing and just be in tune with the divine order, so to speak, and understand the moment of now. It's not categorized, it's just another means by which we can get there, a vehicle to get to get back to loving ourselves, and getting back to, ultimately, loving in general, you know what I mean?"

Rennie, I've got your one word answer right here: Yes.

[ Santa Cruz | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

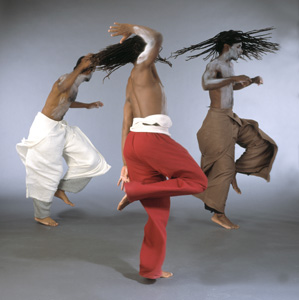

Below: Dancers execute Harris' melting pot of cultural influences in 'Facing Mekka.'

"All the stuff that's written is other people's perception," Harris says, casually shutting me down from his home in Philadelphia. I like him immediately.

Harris Meant: Rennie Harris doesn't want people picking his brain about 'Facing Mekka.'

"In his mind, he had an idea of what he wanted," says Ross, "but it was really like, 'just go create and present your ideas to me.' Things that I would think that he would want, he wouldn't want. In the last five or six months, I started to get where he was trying to go with it. We would do a rough demo, and if it inspired him we would finish it, or make changes so that he could work on the choreography. I think we did like 15 hours of music, which he cut it down to an hour and 45 minute show. Right before the preview in January, we had nailed what he wanted."

Facing Mekka will be performed on Monday and Tuesday, April 14 and 15, at 8pm at the UCSC Theater Arts Mainstage. Tickets are $22-$25 general, $17-$20 seniors and students with ID, $12 UCSC students with ID; call 459.2159. A free screening of turntablism documentary film Scratch starts at 5:30pm at the Second Stage Theater on Monday and at the Experimental Theater on Tuesday.

From the April 9-16, 2003 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.