![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

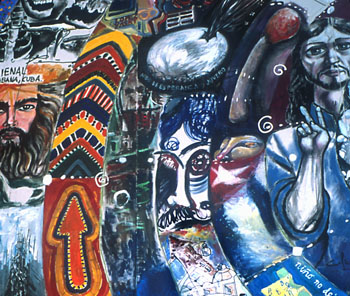

Connective Issue: The colorful new Mural 2000 is a tribute to the Mural Cuba Collectiva of 1967.

View to a Vision

Santa Cruzan Dina Scoppettone made art--and art history--in Cuba

By Andrea Perkins

AT FIRST it's hard to imagine the diminutive Dina Scoppettone wheeling and dealing with high-ranking officials in the Cuban government, but one soon realizes that this 25-year-old could orchestrate a hot-pants convention in Yemen if she put her mind to it.

With a degree in art history from UCSC and an M.A. from the Courtauld Institute of Art at the University of London, Scoppettone could have gone on to get a Ph.D. or accepted a job as a junior specialist at Sotheby's in New York. "But I wanted to do something as an art historian proper," she says. It turns out that meant making art history.

Scoppettone's idea to bring 100 artists together in Havana to paint a 20-by-30-foot mural had its genesis in her thesis project on the Mural Cuba Collectiva of 1967.

Urged by Wilfredo Lam, Cuba's most famous artist, Fidel Castro brought the avant-garde artists, intellectuals and writers of the day to Cuba to make art for the National Museum. For four months in 1967, the artists' expenses were paid for by the Cuban government. They stayed at the finest hotels, received boxes of cigars and red roses and wined and dined with leading Cuban officials at the famous Tropicana Club. The experiment culminated in a huge collaborative painting, a bright, bold tribute to Cuba and the revolution in the form of a spiral radiating outward, divided into separate sections for each artist. During the actual painting of the mural, dancers and actors portrayed revolutionary scenes for thousands of spectators.

In 1998, after receiving her M.A., Dina decided that she would hunt down the 1967 mural (no one knew exactly where it was), restore it, organize contemporary artists to create another collective mural in tribute to the first--and then take both murals on tour to museums all over the world.

"The idea of taking the piece out and restoring it and exhibiting it seemed to me to be a way to offer a totally different and fresh perspective on this idea of Cuba," Scoppettone says.

Cultural Diplomacy

SCOPPETTONE, WHO possesses more charisma then a cult leader, fiery brown eyes and a big smile, has deep roots in Santa Cruz. Her grandfather was Judge James Scoppettone--"the judge" in town," she says. The famous Judge Scoppettone adjudicated in Santa Cruz for 20 years, acquiring a reputation that still gets his granddaughter extra special service in many shops and restaurants. "He was greatly respected," Dina explains with characteristic animation.

Dina grew up in Scotts Valley, on a ranch once owned by Alfred Hitchcock. Her love of art was inspired by her father, James Scoppettone, who is a widely exhibited impressionist painter.

Family friends introduced her to her first Cuban contact, who phoned her in Kauai, where she was staying with her friend Roberta Haas. The "Cuban contact," who prefers to remain anonymous, told her he could put her in touch with the right people.

Then he added, "The first thing that you really have to understand and never forget is that you can't trust anybody, not even me. Anybody regarding Cuba ... don't trust them, and consider that they're thinking that of you, too." It was daunting, but also intriguing, in a James Bond kind of way.

As Scoppettone pulls out exhibition catalogs of the artists who participated in the mural, a photo of her and Al Gore accidentally falls out onto the table. Dina is full of surprises.

"Oh yeah, Al Gore," she deadpans. While Scoppettone was in Kauai, Al and Tipper Gore just happened to drop by Haas' star-shaped glass house, which is famous for its tropical pond and waterfall. After taking a dip in the pond, the Gores visited a little with Haas and her guests. Scoppettone, who had wanted to be a diplomat when she was a kid, took the opportunity to acquaint the then-vice president with her "Cuba project."

"He kindly reminded me that there was an embargo and then basically told me to stay out of Cuba," she recalls, laughing.

Nonetheless, and without knowing if the Cuban government would ever grant her permission, Scoppettone started raising support for the project. Intermedia Productions in England wanted to do a documentary film and agreed to finance her first trip to Cuba. But Scoppettone soon broke off the arrangement when she learned that they wanted to sensationalize the whole thing.

"I am geared toward this idea of cultural diplomacy," she explains, "really using the arts as a way for people to discover each other."

Scoppettone, then 23, flew to Havana and dialed the number given to her by her one contact. It turned out to be the old teacher of Rafael Acosta, the president of the Consejo Nacional Artes Plasticas (National Council for the Arts).

"You're going to help save Cuba," the teacher told Scoppettone when they met. Thus began a two-year process of trying to get President Acosta to say yes to her proposal. It wasn't easy. After Scoppettone was finally given a private viewing of the 1967 mural in the National Museum's warehouse on the last day of her second trip to Cuba, she (and several other museum staff members) burst into tears. "It was an unforgettable moment to be let into the inner sanctum that way," she says.

Paint, She Said: An artistic odyssey involving 100 artists began with a phone call to an anonymous Cuban contact.

Persuading the Presidente

DINA CONSULTED with numerous experts, insurance firms, businesses, curators and artists all over the globe. She won people and institutions over to her cause, though working with the Cuban government proceeded at a tropically slow pace.

"They [the Cuban government] just never really believed that such a project could be done by an American," she says. "I was showing up persistently, constantly at their heels, flying to Cuba or Paris to meet with Acosta. There were countless meetings at the big round table in his massive office. Cigar smoke wafting around, you know, the classic scene, the fan turning, little trays of tea in 50-year-old china, the table full of men and one note-taker girl and me.

"It really came down to trusting each other, which as I had been warned early on, was a near impossibility. I just wouldn't give up. I'd say, 'Listen, this whole project can be magnificent. I have enough support lined up to make it huge. We can invite U2 if we want, if you just give me a signature that says the Consejo and the Ministry of Culture approve of this."

She wasn't joking. She really would have brought U2, or Smash Mouth, who told her they were interested. But the Ministry wouldn't give approval until she showed them signatures from funding sources; and the funding sources wouldn't commit until they had paperwork from Cuba.

Frustrated, Scoppettone decided to scale down her original vision and big budget. She reckoned that the most practical course of action would be to stage the mural during the Havana Biennial, when the world's most prominent contemporary artists--who just happened to be the same ones she had invited to work on the mural--were already going to be in Havana. The Biennial was in November 2000. In September, Scoppettone finally got permission from the Cubans.

Because Scoppettone envisioned the new mural as an homage to the mural of 1967, she wanted to stage it in the Cuban Pavilion where the painting of the first one had taken place. "But they [the Ministry of Culture] were like, 'No, we have a spot for you off in the harbor in a dilapidated warehouse,' " she says. Scoppettone was not interested in holding the event in a dilapidated warehouse in the middle of nowhere.

Several more weeks of high-powered wrangling ensued before she got them to agree to the Cuban Pavilion in the Vedado district of central Havana. "Which was great except for now I only had three weeks to secure funding!" Scoppettone says.

At first, a great percentage of the support came from English sources. "It was very difficult to get people in the United States behind anything having to do with Cuba," she says. "It's not so much like that now. I think that in the two years I've been involved with this, there has been a great evolution in attitudes about Cuba. Cuba is very fashionable now, and because it was such a sexy topic in the U.K., it helped to generate interest."

One of Scoppettone's biggest contributors was the Florida-based Latinanet.com, which agreed to give her financial support in exchange for a chance to bid on documentary film footage. Enter Dale Djerassi, independent filmmaker, patron of the arts (and son of Carl Djerassi, inventor of the birth control pill). Dale had been following the project for some time and agreed to produce the documentary with her. Other local support came in many forms, such as the thousands of tubes of paint (not easy to get through customs) donated by Lenz Art.

Copacabana

ON SUNDAY, Nov. 19, 2000, at noon, four hours ahead of schedule, artists such as Michael McCall, Ever Fonesca, Lopez Oliva and Cesar Leal (who also painted on the 1967 mural), assembled in Havana's Cuban Pavilion. Six tautly stretched panels of canvas, attached to each other with industrial strength Velcro, were blank except for a charcoal outline of the same spiral design that graced the 1967 mural. Scaffolding made out of wooden planks and hollow steel bars allowed the artists access to their designated squares.

All day and into the night, Scoppettone prayed while the artists teetered on the scaffolding, paint and water flying. Spectators gathered to watch and participate in the festive atmosphere. Even Metro Santa Cruz cartoonist Steven DeCinzo was there, painting in a prominent square near the center. Unfortunately (or fortunately), DeCinzo painted over what he had started, explaining to Scoppettone that he appreciated being included in the project but that he was afraid that what he would paint might be too inflammatory.

Mural Cuba Colaborativa 2000 was a major success, not only as a work of art but as an event. "It wasn't just something that the artists were into," Scoppettone says. "It was something in which everyone could really find a spirit. It's amazing to imagine in the center of Havana, at the Cuban Pavilion, an American group of people, because a lot of people came down from the States to be there for the event as well, and all these artists from all over the world painting together.

"It's something that you would never expect to see in the current political situation, what with all the rhetoric that gets espoused about Cuba and the United States. There wasn't anything negative about it. Everyone was really up and into working together. It was a collaboration, a collective. I wasn't up there on a microphone talking to them. I was in there, giving them paint."

The popular Cuban band Mezcla was lined up to play the event. The Ministry of Culture, however, became concerned about the growing crowd "having too much fun." Luckily, Scoppettone had anticipated that move and had a DJ and his collection of disco as backup, plus plenty of rum and coke to keep the creative juices flowing. The painting continued from noon to 10pm, at which time security guards started painting on the artists.

"As soon as the suits and straight-laced ministry guys who were overseeing us saw the security guards painting on each other, they put a stop to everything," she says. "The security guards had crossed the line of being security guards at that point. Everyone was having an amazing time interacting, painting, speaking different languages, laughing.

"It was all very much in the tradition of the 1967 mural. But whereas the 1967 event was pure propaganda, the event I staged was the absolute other end of the spectrum, where the government was not really in charge of the project. In '67 it was pure nationalist fervor. It wasn't that the 2000 event was 'anti,' it just didn't glorify the ancien régime."

The 1967 mural is covered with bold reds, yellows and blacks, images of Che Guevara and slogans like "Viva la revolucion." The 2000 mural, on the other hand, is full of bright pastels and includes depictions of a Cuban flag that seems to be shredding itself, and many references to light and flight. The center, painted by the Indonesian artist and Havana Biennial favorite Iweng, is done entirely in white, creating an explosion of radiance at the very heart of the mural.

Today, Dina Scoppettone is based in Santa Cruz where she is the founder of Omniocular Global Art Society, or OMNIO, a nonprofit organization intent on staging art exhibits and film projects worldwide in order to stimulate cultural awareness. Scoppettone had initially hoped to take the unfinished canvas to Santa Cruz to have students here complete the open segments as a symbol of friendship between the artists of both nations. However, several days of negotiations with Cuban officials, who cited hostile United States policies toward their country, made it clear that the mural would not be traveling to California anytime soon. So Scoppettone stayed in Havana long enough for Cuban artists to complete the project.

She is still working out the legal details of getting the mural, which has been declared a Cuban national treasure, out of Cuba so she can take it on tour along with the 1967 mural. When not on tour, both murals will be on permanent exhibition in Cuba's newly refurbished National Museum. She is also busy planning future projects, one of which is an International Film Festival in Santa Cruz, which she aims to launch in October 2002.

"I consider myself to be a visionary," she says modestly, "in the literal sense, not in the glorified sense." The name of her organization reflects this. Omni means "all" and ocular mean "vision." It is also a reference to the murals themselves. There is something "all-seeing" about them. Incorporating 200 different perspectives in a design that spirals outward, with pupil-like centers, the murals gaze at two different eras in Cuban--and world--history.

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by Susanne Neunhoeffer

Photograph by Susanne Neunhoeffer

For more information and pictures of Mural Cuba Colaborativa 2000, visit www.omnio.org.

From the May 9-16, 2001, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.