![[MetroActive Music]](/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Leaps and Bounds

New Music Works steps through the 20th century with a program pairing adventurous music and choreography

By Scott MacClelland

PHIL COLLINS COULD be accused of gilding a lily. In his New Music Works program "Quantum Leaps," May 13, he served up an incredibly rich banquet of music which needed no enhancements. But enhancements came anyway, in the form of choreography and dance conceived and imposed whether the music needed it or not.

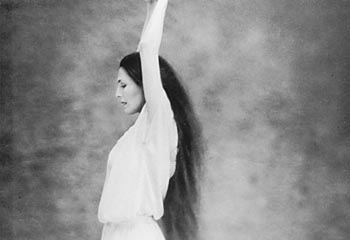

Did this help or hinder? Both. Tandy Beal devised a spatially surreal reflection of Morton Feldman's I met Heine on the rue Fuërstenberg, a narrative choreographic scene with Magritte images in life scale and miniature. The thinly scored but potent musical tissue featured mezzo-soprano Marie Bafus in a wordless cantilena. Feldman did not have dance in mind when he composed this work, and, despite Beal's unique creative talent and vision, it did distract from the concise and sure-sighted music.

Nevertheless, the nine dancers, glitter fairy, man walking slowly, aluminum foil islands, broken egg, toy boat and wagon, briefcase crossing the stage and the passing of a note all inspired wonderment, if not puzzlement, at how they might have connections to the music.

On the other hand, J's Way/S-Bridge by choreographer Therese Adams did Lou Harrison's Suite for Violin, Piano and Small Orchestra a disservice. This is one of Harrison's most haunting and memorable works, as much for the influences the composer attributes to other musicians as for his luminous embrace of concise forms. Adams' work lacked discipline at every level. No distinctive or meaningful choreographic idea distinguished her work from one movement to the next. The recurrence of one (of three) dancers who fell down on her back with each entrance added no credibility to Adams' default mode of figures running on stage, twirling about once or twice and running off. I've seen better choreographic work, from design to execution, in high school dance programs.

THE HARRISON, like other works on the program, enjoyed a tasty and satisfying read by the ensemble, its many solo cameos lovingly presented. Likewise lovingly chosen were the notes about Charles Ives' Violin Sonata no. 4, the program's opening work, written years ago by Lou Harrison (whose first professional production of Ives' Third Symphony led to a Pulitzer Prize for the composer). As "Quantum Leaps" go, however, the Ives was a leap backward. Ultimately, Ives' was a nostalgist, a man who took delight in presenting the old music in startling new ways. But the musical references always go back to the past, to the marching bands and church hymns of his youth in rural Connecticut. Violinist Cynthia Baehr and pianist Teresa McCollough imparted those same yearnings to "Tell Me the Old, Old Story," "Yes, Jesus Loves Me" and "Shall We Gather at the River."

From this intimate reflection, the NMW ensemble moved on to play Ruth Crawford Seeger's Music for Small Orchestra of 1926. Its two movements--Slow; pensive and In roguish humor; not fast--gave this remarkably gifted and circumspect composer some locally long-overdue exposure. Crawford (who became the wife of Charles Seeger) was early drawn to the sensual dissonances of Alexander Scriabin and smoothes those qualities into a savory melange nicely laced with subtle musical bitters.

The apex of this program, Henry Brant's Glossary, runs the gamut of spatial music, the primary interest (and reputation) of the 87-year-old Santa Barbara composer. Marie Bafus was the only one of 13 performers who ambulated throughout the room to sing a "libretto" of computer terminology. This was Brant's last work--of the 20th century. (He's looking for new commissions, if you've got the bucks.)

Brant himself played a small pipe organ on stage (after conductor Phil Collins stepped from the podium to kick-start it) in close proximity to harpist Jennifer Cass. Keyboardist Michael McGushin and percussionist Mark Veregge stood opposite, on the UCSC Recital Hall stage. The others, strings players, winds and, conspicuous in his presence, saxophonist William Trimble, were arrayed up the steps and across the top landing of the room. All parts were strictly notated by Brant, but starting and stopping, even with cues from Collins, was left somewhat to chance.

This surround-sound show lasted over 30 minutes, kept everyone in suspense, and, at one point and another, took the audience by surprise (which is just what music is supposed to do.)

I can be accused of remembering the experience overall more than its singular elements, and hope Mr. Brant doesn't mind. If such an idea turns you on, and you play guitar, you are invited to participate in one of two NMW performances of his Rosewood for 100 guitars, scheduled for Nov. 18, under the direction of David Tanenbaum. (Phone 427-2225 for more info.)

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Distracting Dance: Though Tandy Beal's choreography added a unique talent and vision to the New Music Works Ensemble's reading of Morton Feldman's 'I Met Heine on the rue Fuërstenberg,' the dance distracted from the sure-sighted music.

From the May 17-24, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.