American Gothic

Life on Hold: Former El Salto Resort owner Elizabeth Blodgett answers the phone at her son's bed & breakfast, Monarch Cove Inn.

How mismanagement and family feuds reduced a once-famous vacation playland to scattered shards of real estate

By Kelly Luker

CAT URINE. The scent lingers everywhere throughout the acres of trails and cottages on this prime oceanfront property perched on the bluffs overlooking Capitola. The sharp ammoniac odor is inescapable, the legacy of hundreds of feral and domestic cats that have called the El Salto Resort home since Elizabeth Blodgett took ownership decades ago.

Once a favored getaway for Santa Cruz's well-heeled and genteel crowd back in the Roaring '20s, it is somehow fitting that the El Salto resort creep into old age like its owner--with cats as its constant companion.

The stories of Elizabeth Blodgett, her son Robert and the resort on Depot Hill are inseparable, their paths charting a rocky and interlocking history of eccentricity, family feuds, lawsuits, animal abuse and financial missteps. It is also a story that--like most well-crafted tragedies--leaves a few questions in its wake.

But one question constantly emerges louder than the rest--who was watching out for Lizzie Blodgett?

Like the Brookdale Lodge or Capitola's other fallen beauty, the Rispin Mansion, the El Salto Resort is the kind of real estate that keeps local historians happily digging away at its early secrets. Originally built in the 1890s as a summer retreat for two well-to-do British families, the Robertsons and the Rawlins, the property didn't hit its stride until the 1920s under the ownership of the oil-rich Hanchetts.

Known as "the English Cottages" until it was christened El Salto ("The Sea Breeze"), the property already had hit its first round of fading glory when the Hanchetts purchased it and poured petro-dollars into sprucing it up and adding some much-needed amenities. English flora was imported for the extensive gardens, and the Hanchetts added a fruit orchard, tennis court, livestock and barns to their expanding acreage.

Socialites and the well-to-do and even silent film star Mary Pickford found their way to the little cottages on fog-shrouded bluffs that some said resembled the white cliffs of Dover.

About seven acres were sold in the mid-'40s to the Tabacchini family, whose members vowed to mold El Salto into the latest architectural craze--an auto court. It is this little collection of cottages under the towering trees that Elizabeth Blodgett says she visited on a summer afternoon in 1960, and made an offer to purchase the very next day.

Edge of a Cliff

JUST ONE of THE real estate developers showing an interest in the resort, Ron Beardslee says, "If you wanted to do a case study for Harvard on how to screw up a piece of real estate, this would be it." Although he is putting most of his energy into rescuing the Rispin mansion, Beardslee has followed El Salto's stumbling progress and has offered to manage one of the pieces that is now under new ownership.

To understand what Beardslee is talking about, one need only compare an assessor's map of the area from circa 1959, and another map of the same acreage almost 40 years later. The outlay of the original dozen or so lots that define El Salto--known as Camp Capitola on the survey maps--looks like a shattered plate only a few decades later. What was once El Salto has been divvied up into dozens more parcels, with the logic behind those survey markers known only to Elizabeth Blodgett. There appear to be parcels within parcels, and one parcel that has been offered as collateral on a loan seems to be hovering over the edge of those famous cliffs that are disappearing from erosion at about a foot or so a year.

These broken shards of prime real estate testify to Elizabeth Blodgett's perspective on business decisions made over the years. Loans made to Blodgett could not be repaid. Each time, another piece of El Salto--offered as collateral-- would disappear. In 1989, Elizabeth lost nearly half the remaining resort to her son when she could not repay the nearly $800,000 in loans he had made to her. Robert Blodgett renamed his piece--with eight rental units on it--Monarch Cove Inn.

Elizabeth Blodgett is legendary among local title companies, the folks that shepherd through the paperwork and funding for real estate title transfers. She was known to arrive at Penniman Title before the offices opened and remain there all day, working her way through land deals, loan ideas or parcel-splitting. Insiders who spoke on condition of anonymity say that Mrs. Blodgett evokes both frustration and sympathy. At wit's end, one title company actually 86'd Blodgett from its offices. Yet the company also watched helplessly as the Darwinian ecology of finance played out around the woman.

"Every bloodsucker on the planet has sought her out ready to offer insane loan deals," says one title company representative. Blodgett's spotty track record of paying back loans made the woman with the million-dollar real estate look mighty attractive.

Shelter from the Storm: New El Salto Resort owner Stan Shore plans to invest at least $200,000 to upgrade his piece of the pie.

See Shore Resort

A BIG CHUNK of El Salto broke off just a few months ago and landed in a new owner's lap. Stan Shore happily shows me around his recently purchased section of the historic resort. Although Elizabeth Blodgett is still listed as owner down at the assessor's office, that is in name only. Shore tells me that he and Paul Greenfield foreclosed on Elizabeth for non-payment of loans in February, right before Mrs. Blodgett filed for bankruptcy again.

On this particular day, Shore's slice of El Salto is bustling with activity. About a dozen busy workers are removing trees, installing irrigation and landscape, gutting and rewiring the different cottages. "There was a lot of 'deferred maintenance,' " says Shore delicately.

As El Salto deteriorated over the years under Blodgett's ownership, most of the cottages were turned into long-term rentals. Overnight guests were a rarity. Finally, the resort was condemned by the City of Capitola in 1989 for "serious life safety hazards." A major renovation followed and El Salto was re-opened as a bed and breakfast in 1991, and continued to be a popular site for weddings.

However, there is much more to do. Shore and partner Greenfield estimate that they will be pouring in close to $200,000 in renovations before their portion of El Salto re-reopens by Memorial Day as a bed & breakfast inn. "I'm a B&B lover," says Shore.

Hospitality is not his background, but Shore emphasizes that customer service is. Shore made his money with a chain of auto tune-up shops, Acc-u-Tune & Brake. He sold that business in 1996 and is now a "small-business consultant." Shore says he has an agreement with Robert Blodgett's Monarch Cove Inn to share the two properties--and fees-- when weddings are hosted. Robert Blodgett says that Monarch Cove Inn charges about $2,400 for renting the grounds and an overnight honeymoon suite.

"It will look seamless between the two resorts," figures Shore. Asked what he will do about the dozens of feral cats that still roam the property, the developer says that he will catch them and take them to the SPCA.

It is these feral cats that first brought me to Elizabeth Blodgett almost two years ago. I was working on a story about obsessive animal collectors, a subculture of folks who literally love their pets to death. If Blodgett was developing one reputation among title companies, she also had become infamous among pet protection agencies for another. She had been repeatedly charged with animal cruelty in three separate counties--San Benito, Santa Cruz and Santa Clara--for being unable to care for the hundreds of dogs and cats she amassed at her different properties.

About 200 sick and diseased dogs were rescued from Blodgett's Mountain View home in 1981. Another 50 starving cats and dogs were taken from the El Salto Resort the next year. Yet another 200 dogs were rescued from filthy and overcrowded kennels in her ranch at San Juan Bautista in 1986. Complaints continued to filter in to local authorities by the time I met with Elizabeth Blodgett in 1996.

Pet Peeves

WHEN I ARRIVED early that morning, Mrs. Blodgett graciously offered me pastries from Kelly's and a demitasse of coffee while we settled in to talk about her life and her problems with pets. The acrid tinge of cat urine permeated her office, camouflaging the coffee aroma and dampening any appetite for Danish.

But, Blodgett was anxious to talk about her life, about her accomplishments before the El Salto Resort. Thumbing through scrapbooks, she showed me pictures of nurseries and schools she owned and ran in Los Altos and Palo Alto. She could have been anyone's favorite teacher, standing there in faded photos with youngsters on ponies or with her students gathered together for graduation day. Mrs. Blodgett thumbed through letters from those students who have kept in touch over the decades.

But, Elizabeth Blodgett was less enthused to discuss her difficulties with pets. As far as she was concerned, it was an employee problem--"you can't find good help," she said at the time.

In March of this year, the animal--or employee-- problem resurfaced. Authorities were called again to her 85-acre ranch on Rocks Road outside of San Juan Bautista. They found 70 dogs and about 30 cats kenneled throughout the house. Three dogs had already starved to death. Dozens more were euthanized by Elizabeth's veterinary at her request. Authorities then went to the El Salto Resort that same week and rescued another eight dogs and 11 cats. Three cats needed veterinary care.

We meet again. Mrs. Blodgett looks more feeble than she did two years ago, but she is still gracious and willing to talk. Again she points the finger of blame to her employee, ranch caretaker Paul Coates.

"He said he wouldn't let me in because I owed him money," says Mrs. Blodgett. "I called the sheriff and reported he threatened my life." It's only then, she says, she entered the San Benito County ranch and discovered animals were being neglected.

Yet Coates has a slightly different version. He is waiting to walk me through the San Juan Bautista house, a once-magnificent home that has fallen into serious neglect. Junked cars are parked in front, the house's windows cracked and carelessly covered with old sheets.

"What took you so long?" Coates asks accusingly. He is not talking about my commute--he wants to know why he called every agency in San Benito County for the past five months but no one would come out to investigate. He says he even went so far as to call the FBI, but each agency gave him the run-around.

Coates says when he was hired five months ago, Blodgett promised to pay him $400 a week. He has yet to see any of that money, he says. Asked why he didn't just leave, Coates says he was "trapped." His brother Larry Coates, who works at El Salto, got him this job and he needed to get out of Los Angeles to escape "some problems." He also says that he was admitted to County Mental Health after authorities arrived to confiscate the animals. He won't be specific, but says, "the barking all day, all night, 24 hours--I hardly ever slept."

As Coates walks me from wing to wing of the large house, surreal images of a doggie Dachau come to mind. Long rows of rusted and fenced-in kennels--now empty-- are housed down the halls and in various rooms. Dozens more fill in the backyard. Coates cautions me not to go into another upstairs room that was used to house dozens of cats. He is worried about fleas--even though it's been more than a month since the animals were removed by authorities. I ignore him and in a matter of seconds my legs are black with the ravenous insects.

Pen Pals

PAUL COATES WASN'T the only one suffering from mental problems. The dogs were what's known in pet protection parlance as "kennel crazy" or "cage-shy," the result of what Coates says are Mrs. Blodgett's strict orders that they were not to be taken out for exercise or for play. The animals spent their lives penned up.

It is not as if Elizabeth Blodgett's animals suffered under the cloak of secrecy. Two years ago, San Benito County animal control officer Rich Brown insisted that Blodgett's ranch was inspected on a regular basis. Brown was recently transferred to the San Benito County Sheriff's Department and did not return repeated phone calls.

Then there's Blodgett's veterinary, Dave Carroll, DVM. Carroll has worked with Blodgett's animals for 20 years and says the deterioration of pet care began not long after he started working with her. "When [Elizabeth] was healthy, she took great care of these animals," says Carroll. "People don't understand that she built that facility [in San Juan Bautista] just to house her dogs."

The vet says that this last time he was called, he euthanized about 50 "young, healthy animals" at Blodgett's request.

Did he have any ethical concerns about that?

"The SPCA was going to impound them and was probably going to do it anyway," he replies.

Did he have any ethical concerns about continuing to work with Blodgett all those years, knowing that she was endangering animals?

"At times, I did," Carroll admits. "But I never thought there was anything wrong with trying to improve the quality of life."

Paul Coates wonders why no one was keeping an eye on Mrs. Blodgett, who had amassed a lengthy history of non-compliance. The two obvious choices for that role would have been those who knew her best--public officials and her son Robert Blodgett.

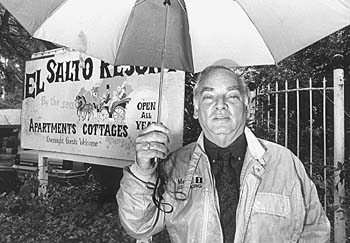

Rising Son: Robert Blodgett (foreground) and partner Doug Dodds hope to purchase back part of the El Salto Resort that has been sold to other investors.

Courting Disaster

THE MONARCH COVE INN takeover was not a pretty experience, it appears. Mother and son sued and counter-sued each other over the affair. Besides taking each other to court, the Blodgetts have kept a fair share of attorneys busy over the years as both defendants and plaintiffs. There are 14 court cases involving Robert, and more than 50 involving his mother that have been filed in the last 10 years in Santa Cruz County.

There are small claims cases about unpaid wages. There are disputes over wedding and rental deposits. There is the flurry of lawsuits that followed the accidental drowning of a guest who slipped off the cliff into the surf below in 1995. There are the defaulted loans and the two bankruptcies filed by Elizabeth Blodgett. There was a bitterly contested conservatorship for Elizabeth Blodgett's longtime companion, Richard Tarmey, that pitted Elizabeth against Tarmey's relatives.

The court records paint a picture of an older woman that, at best, made questionable business decisions with valuable property, leaving her prey for financial speculators. Her personal proclivities towards pets--what some would label a disorder--caused the suffering of hundreds of animals over the years. During the course of several interviews for this story, one phrase surfaces time and again when the subject of responsibility for Mrs. Blodgett arises--"If it was my mother ... ."

Robert Blodgett is difficult to pin down for an interview. He breaks two appointments, then arrives a half-hour late for the third. A good-looking guy in this fifties who stays physically fit from daily work-outs, Robert is also a bundle of restless energy. He often runs his hands through his graying hair, and a foot taps impatiently as I ask questions.

He wants to talk about his impending plans to buy the El Salto Resort back from Stan Shore and Paul Greenfield. Along with partner Doug Dodds--who already owns several parcels of the former El Salto-- Robert Blodgett says that he expects to be able to consolidate the properties in the next week or so.(When contacted, Shore tersely replies, "His offer made its way rapidly into my wastepaper basket. At this point, there's nothing on the table.")

Robert also owns property adjacent to Monarch Cove Inn, in an area known as Escalona Gulch. Asked what he does for a living, Robert becomes vague, mentioning stints as movie producer, a rock concert promoter and an importer--"emeralds, furs"--and says he's invested well in Santa Cruz real estate.

It is even more difficult to get Robert to talk about his mother. Each time we get close to the subject of Elizabeth Blodgett, Robert answers abruptly, "I don't want to talk about it."

But, eventually, he does. He admits that the property kept shrinking because of Elizabeth's poor business decisions. He says that even he has called the animal control people to visit his mother. "But, she's her own person," Robert asserts over and over.

But maybe, Elizabeth Blodgett wasn't her own person. It is one of the most difficult decisions an adult child must make, determining that an older parent may no longer be capable. I tell him, by example, of how difficult it was to take away my aging father's car keys. His eyes cloud with pain for just a moment.

"How can you step in when you're being sued all the time?" Robert asks. He explains that attorneys advised him he would not be permitted conservatorship, since he has liens against his mother.

Kitty Litter

IT'S BEEN A DIFFICULT relationship. But, after years of not speaking to each other, of suing each other, the final burden of caring for his aging mother is on Robert Blodgett. It is he who checks on her every day, and who, on one of my visits, was headed out the door to bring his mother home from the hospital.

At 76, Elizabeth Blodgett's body is failing. There is the heart trouble that landed her in the hospital for a week recently, but today she is answering the phones for the Monarch Cove Inn office. A late spring rain is falling outdoors as we sit and chat while I wait for her son to show for his interview. She is gracious as ever, offering up memories of the early days of El Salto. The ever-present smell of cats is with us, of course, but I realize that after a few visits, I'm getting inured to it. It is part of the landscape, like the eucalyptus trees and the faded wooden sign that advertises her beloved resort.

Asked how she likes the changes brewing up here, Mrs. Blodgett is blunt: She doesn't. They've cut down her favorite trees, some that are 60 years old. She doesn't trust what they're doing to the inside of the cottages. And, most importantly, Elizabeth doesn't think these new owners understand the nature of a bed & breakfast inn. She loves the hospitality business. The phone rings constantly as we talk, and it's true--Elizabeth makes a personal connection with each person that calls.

"We'll so look forward to having you!" she tells one prospective guest. With another, she rhapsodizes about the ocean view. A young couple come in to drop off the keys to their cottage, telling Elizabeth how much they enjoyed their stay.

Elizabeth Blodgett is in her element here. But it must be difficult as she looks out the open office door on the construction crews workers scurrying about her former playground, changing and rearranging her indelible stamp. But, she's says, she's not that worried.

"Robbie's going to buy it back," she says confidently.

As I glance out the door, another feral cat slinks through the rain into the bushes.

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

From the May 21-27, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)