![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

All Stalk, No Action

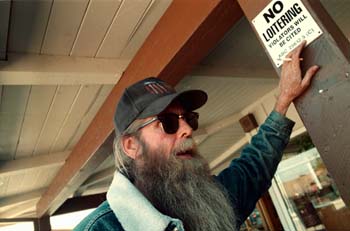

Sign Up Here: Former candidate for sheriff Richard Quigley is still tilting at constitutional windmills.

Is it stalking or is it an exercise in constitutional rights? Both Claudia Easterby and Richard Quigley think they have the answer.

By Kelly Luker

'THIS IS THE worst damn mess," sighs Claudia Easterby. She is sitting in her cramped office at the Gottschalks department store in the Rancho del Mar shopping center, where she has been manager since 1989. She is gesturing toward a drawerful of documents--lawsuits, restraining orders, crime reports--all written in legal language that Easterby believes doesn't begin to do justice to the last four years she has endured. If she had it to do all over again, Easterby admits she'd do things differently.

"I'd just let him sit out there and rant and scream," she says.

Easterby is referring to Jerry Henry, who has made the common area in front of Gottschalks and two neighboring businesses, the Aptos Coffee Roasting Company and the sheriff's substation, a home away from home. Although Henry may be "annoying," in Easterby's words, the self-described "psychologically injured" street minister is not the source of Easterby's sleepless nights and troubled days. Nor is it Henry who has driven Deputy Sgt. Joseph Hemingway to hire an attorney to protect himself from slander charges.

That dubious honor belongs to Richard Quigley, a former car salesman who says he has dedicated himself to fighting the "police state" and protecting his and others' constitutional rights. But Easterby and Hemingway say that in his quixotic quest, Quigley has trampled all over theirs. In this battle, the winner will be whoever can hold out the longest.

Kid Clusters

A TALL, GAUNT MAN with wispy gray hair past his shoulders, Quigley looks every bit the "weird hippie" he describes himself as. He is also bright and articulate and can quote federal and state statutes. It was an incident with a Capitola police officer in 1984 that brought Quigley to his obsession with constitutional rights. Quigley says the cop was hostile and violent. The cop said he was defending himself.

"I had heard people talking about a police state and I thought they were crazy," remembers Quigley. "All the things I didn't want to believe about this democracy, they were there. Do cops lie? All the time."

Over the years, Quigley has found plenty of causes to champion. The motorcycle helmet law led him to start a loose-knit organization called the United States Freedom Fighters with a website where people can compare notes on what he calls the erosion of the Constitution.

But Quigley grabbed onto a particularly thorny cause when he decided to champion one of society's most feared elements--teenagers.

Like many shopping centers, Rancho del Mar has been a mecca for kids to hang. The center's manager, Greg Schmitt, says that the area in front of the coffee shop where Aptos Coffee Roasting Company is now located had become a popular meeting place years ago. However, according to Schmitt, it was the coffee culture of the early '90s that began attracting larger numbers of after-school crowds and, increasingly, street kids during the day.

Schmitt fielded growing numbers of complaints from customers saying they felt intimidated by clusters of teenagers blocking the sidewalks. In response, shopping center management stepped up security patrols in 1994. A year later, the Aptos sheriff's substation relocated in Rancho del Mar.

When the simmering stew of customers, shop owners and teenagers began to boil over, it was Richard Quigley who turned up the heat.

Plague of Locusts

THE FIRST VOLLEY was fired in 1997, when Easterby asked Quigley to move from his seat in front of Gottschalks and he refused. He says he was planning to run for sheriff and was talking to potential constituents. Both say the other one was belligerent, but it was Quigley who got arrested for trespassing and disturbing the peace. A month later Easterby got a restraining order against Quigley, which he has violated three times. Aptos Coffee Roasting also got a restraining order against Jerry Henry that requires him to stay at least 20 yards away.

Quigley is convinced the orders are unconstitutional and part of an effort to run off the teenagers, who have claimed Rancho del Mar as a kind of public square.

"The kids are part of the 'undesirables,' " Quigley says. He accuses the storeowners of discrimination against kids merely because of their age and appearance. "For the life of me, I don't know why they do that."

The shopkeepers say they have a damn good reason--the kids were hurting business.

"There's a cumulative effect of customers who come in here and say they won't shop here because of those people," says Al Pepper, owner of Rancho Liquors. His store is next door to Aptos Coffee Roasting Company, and Pepper says the problem has gotten worse since the coffeehouse's restraining order was issued. Now, Henry and his young followers have become a fixture in front of Pepper's business.

"By some judicial whimsy, I have them parked in front of my store," says Pepper grimly. "The locusts are now in my crop."

While Pepper admits that the kids do nothing criminal, they're still frightening to customers.

"They swear, they spit, they play hackysack," the store owner says. "They're energetic and rambunctious and do the things kids do."

If the Suit Fits

QUIGLEY HAS LOST count of how many lawsuits he's filed, but court records indicate he has filed 13 since the lawsuit against that Capitola cop. Sgt. Dave Deverall, the Aptos substation's first sergeant, believes he is named in "two or three." The sheriff's department, Gottschalks--in fact, most everyone who has crossed paths with Quigley--find themselves in court.

Hemingway recalls that Quigley even put up "Wanted" posters on Deverall when he was substation commander. Deverall chuckles.

"He wanted to arrest the manager of Rancho del Mar," he recalls. "At one point he was reading me my Miranda rights."

For Quigley, fighting the legal system has become a full-time job. He's been charged with a half-dozen violations since 1997: for driving with a suspended license, trespassing and violating Easterby's restraining order.

The most recent arrest was last month when Easterby came out of a meeting at the Capitola Mall to find Quigley's car parked next to hers.

Quigley says it was coincidence--that he had dropped into the mall's food court for a bite to eat and that he has no idea what Easterby's car looks like.

"I don't know the nature of the woman's psychosis," Quigley says, "but I promise you I have not followed her."

It's not an excuse his accusers are buying. Weeks before the Capitola Mall incident, Easterby says she looked in her rearview mirror and saw Quigley driving behind her, at least twice. She reported this to Hemingway, who suggested she get a cell phone.

Hemingway also scoffs at Quigley's claim of ignorance.

"He's had this restraining order against him for a year and a half and he doesn't know what her car looks like?" Hemingway has suggested that Easterby park her car in view of the substation.

Asked if he thinks Quigley is an actual threat to the Gottschalks manager, Hemingway pauses. "Quigley's bright enough to play it right to the line [legally]," the sergeant says. "But I have concerns."

Oh, Henry

WHILE QUIGLEY TENDS to make his opponents' lives miserable in the courts, Jerry Henry relies on a loud vocal presence. Most recently, Henry was arrested after using a racial epithet with an African American security guard. Henry denies the charge, and the accusation that he is a racist.

"I never spoke to [the security guard]," declares Henry. "I refer to myself as a nigger. I feel very much like one. Rosa Parks wasn't allowed in the front of the bus and I'm not allowed in Gottschalks."

The security guard is not alone. Five other people have filed complaints with the sheriff's department about Henry's rants because of his use of "nigger."

Henry has lived on disability for the last 10 years, since a nervous breakdown during his last job as a food inspector. He says he is not mentally ill, but "psychologically injured." He calls himself a "street minister," and has been active in delivering food to various homeless services--that is, until his license was temporarily suspended by the DMV as the result of a request for a retest by Sgt. Hemingway.

"I've tried to do the best I can," Henry says. "My head's on pretty good, but sometimes it gets spinning." Then Henry's voice rises a few decibels. "They destroyed my life," he says and begins to cry. "I've been ostracized from a great amount of this community."

Like Quigley, Henry has racked up at least a half-dozen violations since 1997, mostly for disturbing the peace. But Henry won't be going down alone.

Recently, a flier surfaced in Aptos with an "article" written by Richard Quigley about Henry's arrest for the racial epithet on one side. On the other side was a reprint of a 1995 Santa Cruz County Sentinel article about an incident involving Hemingway. No charges were filed in the incident, but shortly afterward Hemingway was transferred from his position as sheriff's spokesperson and internal affairs officer to run the regional substation. Quigley says he handed out the fliers, and Henry admits to inserting some into copies of Metro Santa Cruz.

"I've been personally targeted and harassed for doing my job," says Hemingway.

Not that doing his job is doing much good, it appears. Most of the charges against Quigley and Henry have been dismissed because the district attorney's office has declined to prosecute.

"It's a question of if there's a crime being committed and is there enough evidence?" says assistant district attorney Jim Jackson, who has declined to file on Henry's last two citations.

"We get all kinds of restraining orders," Jackson sighs. "Everyone has a restraining order now; it's the thing to do."

Jerry's Kids

ATTORNEY KATE WELLS has carved out a niche defending clients from discrimination by the government. For Wells' clients, alleged discrimination is less likely to be based on gender or race and more on class. Wells is well known around Santa Cruz City Hall for representing the homeless against the sleeping ban. She also represents Quigley and Henry.

"I see this as part of a bigger picture," Wells says. That picture, she explains, is the attempt by the Rancho del Mar shopping center to control access.

"The merchants are deciding who can be on the streets," Wells contends. "It's just continual harassment."

Wells is particularly incensed that they continue to arrest Henry. "He's not perfect, but he doesn't deserve such belligerent treatment," Wells figures. "They should be pinning a medal on Jerry," she continues. "He's gotten several kids off heroin. He's a saint in a lot of ways."

Jeff, age 17 (last name withheld by request), says he has been clean of drugs for 14 months, thanks to Jerry Henry and the other kids down at "Rancho."

"I couldn't have gotten clean without Jerry," says Jeff. "I talked to Jerry and he showed me who God was. I'm a pretty strong Christian now, thanks to Jerry."

Jeff says he's been singled out for harassment, but being clean and sober hasn't kept him out of trouble with the law. He's gotten six tickets in the last two weeks--for trespassing, disturbing the peace and having tobacco (unlawful for anyone under 18).

Jeff is bright, outlining his thoughts about the tension between the shopping center and Henry in a lengthy email. But in an earlier conversation, he showed a disturbing tendency to emulate his friend. More than once, the young man also compared Henry to a "nigger." Asked if he understood how inappropriate the use of that word is, the teenager looked confused. Like Henry, Jeff uses the Rosa Parks analogy to justify the use of the racial epithet.

While Quigley, Henry and the kids want to see their rights protected, so do Easterby and Sgt. Hemingway, who says he just wants to do his job. Easterby says she would like to feel safe when she drives home or walks to her car.

"I'm not the type to back down from this," Easterby states. "But I wish it would just go away."

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

From the May 26-June 2, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.