![[MetroActive Stage]](/gifs/stage468.gif)

[ Stage Index | Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

The English language doesn't have words for the emotions expressed in belly dance

By Andrea Perkins

I PUSHED THE play button on the archaic stereo, and one of the latest Arabic pop songs filled the hot classroom. It was the end of the semester and my class of 8-year-old Egyptian students and I were enjoying a break from our English grammar books. Cairo's ever-present dust filtered in through the open windows. Before I could stop her, Salma (normally one of my best-behaved students) climbed on top of her desk and started to dance with a skill that astonished me.

Performing the customary Egyptian movements that Westerners refer to as "belly dance," she raised one hand delicately to her forehead, stretched the other arm out in front of her and dropped her hip, kicking softly with her foot as she did so, repeating the motion as she pivoted. Soon the entire class had formed a circle around Salma as they clapped to the rhythm of her impromptu performance.

It probably couldn't have happened in the United States, where dance is not a normal part of everyday life. In Egypt, children grow up learning how to dance. For them, dance is just another element in a larger framework of tradition. When I told my Egyptian girlfriends I took belly dancing classes as a teenager, they were puzzled. It was as if they had told me they took shopping classes.

Shimmy and Roll

THE TERM "belly dance," though universally used and understood, isn't really all that accurate. There's a lot more to this dance form then just wiggling the stomach around. Ribcage, head and hip isolations, spins, circuitous arm movements, hip lifts, arabesque traveling steps, figure eights and shimmies (to name a few) require tremendous muscle control and focus.

"The majority of people drawn to this dance form have issues of body image and want to build self-esteem and connect more with their bodies," says Sahar, who has taught Middle Eastern dance in Santa Cruz for 20 years and performed professionally for 25.

Sahar believes that the attraction also lies in belly dance's wide range of expression. "The depths of emotion that are channeled through this dance are not even always safe to feel or acknowledge," she says.

And then there's the music. Most of the belly dance teachers I talked to said it was the music that sparked their initial interest in belly dance. Long before jazz, Middle Eastern music was based on improvisation and used scales and modalities other than the major and minor chromatic scales of occidental music (Middle Eastern scales use quarter tones in addition to the semitones used in the chromatic scale).

Middle Eastern music is evocative and complex, both rhythmically and melodically. It is also highly emotive. In the Arabic language there are specific words, not translatable into English, that describe the various emotions found only in Arabic music. Tarab, according to an Arabic-speaking friend, is the feeling that your soul is shaking. Sharab is a kind of bittersweet sorrow.

When she took her first belly-dance class at age 13, Sahar immediately connected with the music.

"I also just loved the feelings of the movements," she says. "I felt that I'd arrived, that I was home." When she was 17, she started performing as a cabaret dancer in Bay Area nightclubs. As a professional, one of her pet peeves has always been how the public image of belly dance is often based on performances by amateurs who aren't always capable of offering a quality representation.

While her roots are in cabaret- style belly dance--born in the Cairo nightclub scene of the '20s, when Hollywood interpretations of the mysterious, kohl-eyed "Oriental dancer" fused with traditional Middle Eastern dances--Sahar teaches a synthesis of Gypsy, Egyptian, Lebanese, Kuwaiti and Turkish "folkloric" styles. She is also influenced by African, Brazilian and Asian dance. And she isn't afraid of innovation.

"I got the body locks from Michael Jackson," she tells me.

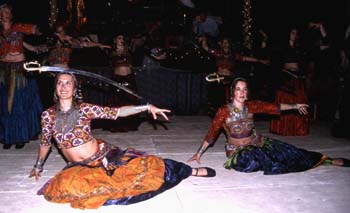

Hip Sisters: Palika (left) and her Heavy Hips Tribal Belly Dance troupe are on the cutting edge of tribal-style belly dance.

Life's a Cabaret

CALIFORNIA IN GENERAL, and the Bay Area in particular, is a hotbed of Middle Eastern dance. A style unique to this continent, usually called "American tribal-style," evolved under the auspices of Carolena Nericcio of Fat Chance Belly Dance in San Francisco, a troupe that fuses Middle Eastern, North African, East Indian, Flamenco and European Gypsy styles. American tribal-style is immensely popular these days, perhaps because it reflects a distinctly Western feminist politic and emphasizes the empowering aspect of the dance. (One word that always comes up when women are talking about belly dance is "empowerment.")

Palika, director of Heavy Hips Tribal Belly Dance troupe and a teacher of the tribal style in Santa Cruz, points out that though it's called "tribal," there are no pretensions toward authenticity. "[Tribal-style belly dance] is not a traditional dance," she explains on her website (www.heavyhips.net), but "rather a modern creation reflecting humanistic sociospiritual needs with an ancient feel." It is important, she continues, "not to pretend that we own the real 'Bedouin dance' or even completely understand it ... We fuse, create and interpret new and old influences into a theory, style or practice of movement."

Though both cabaret and tribal styles use many of the same steps, tribal is generally performed in a group, often at community events such as festivals and parades, while cabaret is a solo dance typically performed as a theatrical entertainment. Costuming is also a matter of contention between the two styles. Cabaret dancers tend to favor sequined "bras and belts," while tribal dancers prefer the more "covered" look provided by wide-legged pants gathered at the ankles and full skirts.

For Palika, troupe and group dancing are ways to celebrate and show dedication to the community. She explains that one of her intentions in teaching tribal belly dance is also to enable "a sense of solidarity, sisterhood and taking control of our bodies and images."

Gypsies Again?

REMOVING AN ART FORM from the culture where it has evolved over thousands of years and grafting it into the context of a completely different culture always raises interesting questions. The usual diluting inevitably strips the uprooted form of its original meaning and relevance. Yet it is naive to think that something like belly dance won't or shouldn't continue to change--as it has always done.

"Belly dancing is a living art which has survived through the ages due to stylistic adaptations in a constantly changing world," writes Sahar in her brief history of the dance.

The current anthropological thinking is that the long, tangled roots of belly dance go all the way back to the dances of temple priestesses in India and the ancient fertility rituals that were prevalent throughout the ancient world. Scholars have also claimed that there are references to this sort of dancing in the Bible. Recently, a dance scholar and performer named Morocco disguised herself as a mute servant in order to gain access to a Berber tribal birthing ceremony. While the men waited outside the tent, the women formed circles around the mother and danced with repetitive abdominal movements while she gave birth. Considered sacred, this dance wasn't meant to be seen by men.

When Gypsies migrated from Northern India in the fifth century B.C.E., they brought what we think of as belly dance with them. The dance spread throughout Afghanistan, Persia, the Middle East, North Africa and Spain, where it became flamenco.

The first time Americans saw belly dance was at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. American feminist Julia Ward Howe described it as "simply horrid, no touch of grace about it, only the most deforming movement of the whole abdominal and lumbar region." Mark Twain is also said to have had a violent reaction to belly dance, in the form of a heart attack, when he saw a dancer known as "Little Egypt" perform.

Some of the first movies ever censored were two Coney Island peep-shows called Fatima's Dance and Danse du Ventre (the term from which English got "belly dance"), in which every frame was painted with bars that left only the dancer's head visible. In an era when corsets were still de rigueur, the undulating torsos and serpentine arms of belly dancers shocked Victorian sensibilities.

In the Roaring '20s, however, anything described with the catch-all adjective "Oriental" was all the rage. Fringe-covered flapper dresses reflected the freedom and flavor of Eastern costuming and the silver screen became cluttered with a series of American movie stars who dressed up like belly dancers and tried to approximate the "exotic" movements of the East.

Going Global

IN ADDITION TO the fact that people are often fascinated by foreign-ness, the way in which many non-Middle Easterners have embraced Middle Eastern dance suggests that something must be lacking in the dance experiences more readily available to them.

After one reaches a certain age, dancing in public becomes sexualized. Sure, you can still go to a rock concert and dance yourself into an ecstatic trance, as I have done on many occasions, but such an environment isn't as secure as a group of female family members and friends. In Egypt, women of all ages get together regularly and dance for themselves and for each other. (Remember how much fun it was to dance with your girlfriends to George Michael and Led Zeppelin for hours?) This aspect of Middle Eastern dance--informal dancing among a group of women--is one of its most vital qualities.

"There are stronger female bonds in the Middle East," agrees Beth Frue, who danced with Fat Chance Belly Dance before becoming dissatisfied with the limitations of American tribal style. These days she teaches Egyptian-style belly dance in Santa Cruz.

"Bert Balladine [an international master instructor] says women have nothing to dance about until they're 35," says Beth. "And that too is part of its popularity. It allows you to be spiritual within the body. In Middle Eastern dance there isn't a split between the two.

"Another reason people like belly dance is because the movements feel really good."

It's true. Belly dance doesn't hurt like the contortions of ballet (though I must admit that previous ballet training has helped my belly dancing technique). It's not that it doesn't adhere to succinct, exact movements. "I'm using muscles I didn't even know I had," is a commonly heard refrain in dancing classes. Even so, it's a dance form that people of all ages and body types can hope to master.

"It is a pivotal time for Middle Eastern dance," Beth continues. "This dance is being practiced around the globe now. Performers, instructors, researchers and academics of many types are just now coming together to address many issues related to this dance form. A number of colleges now offer Middle Eastern dance courses. It's in a special place right now. It's birthing."

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Out of Egypt

Out of Egypt

© 2001 Kyer Photography

From the June 27-July 4, 2001, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.