![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

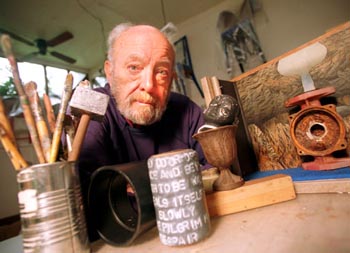

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Out of The Box

Artist Doug McClellan creates whimsical art from myths and

flea market finds

By Julia Chiapella

A PRESSING CONCERN constantly licks at the heels of most artists: how to balance being in the world with the call of self-expression. Lean too heavily to one side, and the work can become voiceless and flat; lean too heavily to the other, and the art may flourish but one's personal life can look like a long train wreck.

We've all heard stories of the latter: Van Gogh's manic depression, Picasso's egomaniacal arrogance, Goya's syphilitic insanity. At the other end, the mannered technicians who made up the 19th-century Realists were enough to drive Mary Cassatt straight into the arms of the Impressionists.

Enough art history. The point is, every artist grapples with the choice: responsibility to one's art versus responsibility to the world. Somewhere along the line, an artist may be fortunate enough to realize the two needn't be mutually exclusive.

Doug McClellan can candidly speak of the responsible path that constituted a long gap in his own artistic work. At four different colleges and universities and through the course of 36 years, McClellan was either dean or chair of art departments, including the art department at UCSanta Cruz, from which he retired in 1986. Though he loved teaching, McCellan felt compelled to be the übermensch, going to the mat for art but forsaking his own--at least during the academic year--in the process.

"This is too romantic for words, but my parents didn't want me to become an artist," McClellan says by way of explaining the superego that inveigled him into the responsible academic life. "I thought at least I'd be responsible. So I went to art school and promised I'd be an industrial designer."

McClellan's manner is easy, his warmth and humor immediately evident. He'd rather not dredge up the past but doesn't make a fuss about doing so. It's all fodder for the artist whose exhibit Wow Boxes is currently on display at the Museum of Art and History in downtown Santa Cruz.

McClellan's small boxes enclose deliciously strange landscapes. To see them, the viewer must look through a peephole, the kind that's commonly found on select front doors.

To see a Wow Box is to enter another world. Built into the 180-degree circular view allowed by the peephole, McClellan uses his own particular combinations of bones, dolls' arms, driftwood and game pieces to concoct tableaus that are patently McClellan: a tragic sense of satire that is screamingly funny.

Whether riffing off the mythology of the Midwest as reflected by The Wizard of Oz or lining up small, plastic babies in front of a concave mirror, McClellan takes Max Ernst's surreal rooms and adds to them some of Marcel Duchamp's insouciant indifference. He builds on the history of assemblage to create his own excruciatingly biting but sublimely droll takes on contemporary culture. And to top it off, he folds within these works a clever nod to our innate sense of voyeurism.

When I first went to see Wow Boxes, I was momentarily breathless at their compact design: 12 boxes sat on two shelves, their tidy exterior belying the macabre scenes within. In fact, I was so immediately caught up in their suggestive mystery that I overlooked the sign illustrating how to view the bosses. Instead of picking them up as the sign directed, I leaned down and put my eye in front of the peephole.

MY INADVERTENT method underscored both the Wow Boxes' unabashed rumble with voyeurism and their subtle taunting at our reverence for museum work. When I realized my mistake, I laughed out loud.

"His sense of humor is always involved in his work in some form or another," says Don Weygandt, a colleague of McClellan's at UCSC who also taught in the fine-arts division. "We tend to think of Doug in relation to his humor, but there's that other side of profundity, of seriousness, that catches us unawares."

Consider this: When McClellan served in the Pacific during World War II, he and his buddies rescued the remaining beer from a burned-out brewery in the Philippines and delivered it to the rest of his squadron.

"It was an act of mercy," McClellan recalls, barely able to contain his mirth. But when McClellan returned from his tour of duty, he used the GI bill to go to Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center and study political art with Boardman Robinson, a well-known political cartoonist. From there, he went on to study murals in the Mexican tradition with Jean Charlot.

These images are consistent with the art and the persona of Doug McClellan. Add to this mix the fact that McClellan has written more than 300 poems during the last eight years--reading at local bookstores and publishing on the web--and another facet of McClellan emerges: he is ineluctably drawn to the written word. Recently, he has incorporated his affection for the computer program Painter with his own haiku to create a folio he's titled A Brief History of Modern Art.

But as far as his choices in style are concerned, McClellan merely credits them to the Zeitgeist. If truth be told, the artist himself will admit to being easily distracted. In fact, he once worried he had no signature style, no compelling voice that marked his work as singularly his own.

Though he graduated in 1947 with a master of fine arts from Claremont Graduate School and was feted with exhibitions and awards, McClellan says it was his turn as dean of the arts division at Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles that got him started down the wrong path.

"I had this weird idea," McClellan says. "I was at Chaffey Junior College, and I was painting, teaching and administering. I thought if I could get rid of one of those hats, I could probably function better. I made the big mistake of getting rid of teaching."

By this time, McClellan was married to Marge (an artist in her own right) and the father to two children. He's now a grandfather, and his marriage is still going strong after 52 years. For 30 of those years, McClellan and his wife have lived on two sun-dappled acres in the Soquel hills. How's that for knocking the image of the unstable artist on its ear?

BUT McCLELLAN'S ARTWORK paid a price for all this stability. During the school year, he administered, leaving his work, which was series driven, for the summer. By chance, it was family vacations to Crystal Cove in Southern California during the early '60s that constituted ground zero for the assemblage work that would give McClellan his artistic license as well as his style.

"We used to take walks with our kids and pick up driftwood," says McClellan, who vacationed with another family also in on the exercise. "Every day, we'd add a few more pieces to the mantel. We did this for five or six years. But it

It was this guilt-free art that saved him from what, for McClellan, was the deadly seriousness of painting. With assemblage he could become a collector of the world's precious detritus, combing beaches and searching flea markets. Bits of bone, small gears, tiny figures would become major players in his unusual landscapes, which combined his persistent humor and his inexorable pull toward life's dark side.

And although much of that devil-may-care quality that characterized those initial beachcombing days is gone, it's obvious that McClellan, whose work has been shown all over the country, has found his niche in assemblage.

With assemblage, unlike painting, he is able to wing it, to riff all the way to the end. Linda Pope, now the curator of the Eloise Pickard Smith Gallery, describes the experience of being a student in the last class McClellan taught at UCSC as a joyful one. "We voted on everything," she says, "even how much money we'd spend at the flea market. It was something like $3.60, and we had to make something for what we bought for that amount."

Pope has referred to McClellan as "a poet, a mythmaker, a magician" and claims that one need only look at his work to confirm those epithets.

"There's an enigma there that's fascinating," Weygandt agrees.

For McClellan's part, he simply has to make things. His adventurousness comes out in his artwork, he says, and not in his lifestyle. He can't be too intentional--it just doesn't work. But balancing the responsible life with the life of the artist was difficult until he retired from academia. Now, finally, he's in revolt.

He chuckles and adds, "I've earned every bit of irresponsibility I have."

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Wizard of Wow: For his 'Wow Boxes,' currently at the Museum of Art and History, artist Doug McClellan turns to mythology--and 'The Wizard of Oz.'

Wizard of Wow: For his 'Wow Boxes,' currently at the Museum of Art and History, artist Doug McClellan turns to mythology--and 'The Wizard of Oz.'

Mixed-Media Mogul: Artist McClellan often raids the flea market to find material for his pieces.

wasn't art. Art was what I did with a paintbrush and paints. This was irresponsible, which was what made it good. The delight in that sort of thing stuck with me."

Wow Boxes shows through Sept. 10 at the Museum of Art and History, 705 Front St.,

Santa Cruz. (831.429.1964)

From the June 28-July 5, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.