![[Metroactive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Mock the Vote

Think the 2000 election was the first time a president has won the White House after losing the popular vote? Think again! It wasn't even the first time an election has been won through tainted Florida recounts and controversial Supreme Court decisions. In honor of America's most patriotic holiday, here's a historical look at the worst election scandals and what they could mean for this election year.

By Art O'Sullivan

His father was elected president of the United States one time, but lost when he tried for a second term. Junior's accession to the presidency was tainted by the fact that a different candidate got more votes and the winner was arranged through corruption at the highest levels. Saddled with this dubious entry for his whole first term, Junior did not want to be a one-term president like his father, and he hoped to erase the stigma of his ill-gotten victory by winning the popular vote for a change.

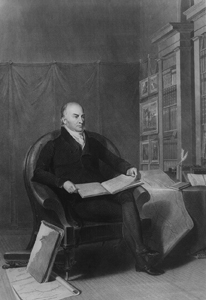

At this point, you're thinking "George W. Bush!" Your enthusiasm is appreciated, but the man in question is actually John Quincy Adams.

Here's another one: In this election, too, the candidate who received the most votes was denied the presidency. The electoral votes of Florida emerged as vital in determining the election's outcome, and there arose a heated dispute as to which candidate had won Florida. In Florida, many African Americans had been prevented from voting, and the true wishes of the state's majority were obfuscated by all manner of electoral fraud and deliberate interference, including an unprecedented one-time-only solution that stank of partisanship on the part of a group of supposedly high-minded individuals interested in establishing the truth, who convened for the purpose of settling the election dispute. In the end, they voted by a one-vote majority to give the presidency to the candidate that belonged to the same party as the purportedly neutral body that picked him. This caused a great outcry in the country, and for years after folks would call this "the stolen election." The prime beneficiary only got to live in the White House for one term.

So this time it's gotta be Bush, right?

No, actually we're talking about Rutherford B. Hayes.

What we have here are two 19th-century presidents whose similar experiences and fates bode ill for Bush in 2004. Although U.S. presidents have never been elected by direct popular vote, no one who took office after losing the popular vote has gotten in honestly, and every one of them has been forced out after a single term. You can be sure the Bush camp knows this and is planning accordingly.

Here is a short history of popular-vote-losing, election-stealing U.S. presidents--and their fates.

The Adams Family

Before 1824, U.S. presidential elections were blatantly undemocratic, just as the founders had intended. The American Revolution had been instigated and led primarily by upper-class types, and many of these people believed God wanted power to remain in the hands of those already rich and powerful. This presumption did not stand well with the revolutionary ideas that all people are equal in the eyes of their Creator and that government derived from the consent of the governed--ideas that propelled the American Revolution and gave rise to the Democratic-Republican Party.

The elitist view lurked within Massa-chusetts' Adams family. John Adams was the first president to lose a re-election bid--in fact, the only one-term president until his son joined him. John Quincy Adams, an elitist like his father, believed that his own responsibility as a leader and an officeholder was to listen not to the people who put him there, but only to his own inner voice. As early American democracy evolved, Adams' elitist views were grotesquely out of fashion.

In the republic's early years, the right to vote and hold office expanded to encompass men who did not hold property or pay certain taxes or belong to a particular religious group, More offices were being filled by popular vote, a trend which bucked the established procedure for picking presidents. By the election of 1824, most states (9 out of 24) allowed the citizens to vote directly for presidential electors. This was democratic progress; however, by now presidential nominees were selected by partisan congressional caucuses. Since there was just one political party, the Democratic-Republicans, whoever "King Caucus" picked became president.

But in 1819, battle-scarred Gen. Andrew Jackson of Tennessee ran for president against the caucus system. While Jackson's conduct as a commander of American forces against British and Seminoles might today earn him a trip to The Hague as a war criminal, and did cause outrage in official circles, this stuff also made him a hero to common people who had also fought British and Indians. And Jackson had climbed from childhood poverty to become a very wealthy landowner and slaveholder. A man of common birth who'd succeeded in war and real estate deserved a shot at replacing those upper-class twits who'd lost control of the economy, members of the elite like House Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky--and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams.

In 1824, both Clay and Adams, like Sen. Jackson, saw the opportunity to put an end to King Caucus' selection of presidents, and each saw his own best chance at the presidency.

According to Congressional Quarterly's Presidential Elections Since 1789:

"When the electoral votes were counted, Jackson had 99, Adams 84, Crawford 41, and Clay 37. With 18 of the 24 states choosing their electors by popular vote, Jackson also led in the popular voting, although the significance of the popular vote was open to challenge." No one had a majority in the Electoral College, so as per the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, the names of the three top contenders--Jackson, Adams and the incapacitated Crawford, King Caucus' ill-advised choice--were offered to the House of Representatives, with each state getting one vote.

Richard Shenkman writes in Presidential Ambition: "Adams won because over the preceding weeks, through winks and nods, he'd struck a series of bargains with various key politicians to win them over to his side. ... And, most famously, at a secret meeting with Henry Clay, Adams left the impression that he'd appoint Clay secretary of state ... Clay delivered the states of Kentucky and Ohio. Adams was elected president. A few weeks after, Adams appointed Clay secretary of state. Adams always insisted that there was no bargain between him and Clay. Maybe he even believed it."

By the election of 1824, the votes of the people were starting to acquire a moral authority, so that awarding the White House to Adams, who had only received two popular votes for every three Jackson scored, was blatantly anti-democratic. Jackson polled 151,271, or 41.3 percent, to Adams' 113,122, or 30.92 percent. While Jackson's plurality was still well below a majority and did not represent all the states, still he was way ahead of anybody else, and the House's awarding of the White House to a distant second-placer was widely seen as a direct rebuff to the will of the people. The diversification of democracy dovetailed nicely with Jackson supporters' charge that the popular will had been denied and that this gross injustice needed to be corrected at the next election.

The iron-willed Jackson knew he was riding a historical tide, but he did not simply rely on that. Instead he organized a new Democratic Party of his supporters across the country, resigned his Senate seat and worked nonstop for four years to see that he was not deprived of his victory a second time.

By 1828, all but two states chose their presidential electors by popular vote. Despite a landmark sleaze campaign by Adams in which he gave his tacit approval to a sex-scandal smear campaign by his supporters, Jackson won 56 percent of the vote, two-thirds of the electoral college and--this time--the White House. The widely denounced "corrupt bargain" between Adams and Clay in 1825 played a major role in the campaign, and after a single term in the White House, the people sent Adams packing--like his one-term father before him--back to Texas ... er, Massachusetts.

Miami Vice 1: Rutherford B. Hayes

The presidential election of 1876 was, for many years after, known as "the stolen election." Use that expression nowadays and people think you're talking about Florida 2000, Jeb Bush and the Supreme Court Five. Here again, the similarities are striking: Rutherford B. Hayes lost the popular vote, but won the presidency anyway thanks to interference with voting and vote-counting in Florida by the governor and to the ruling of a partisan committee.

Coming off Republican Ulysses S. Grant's two scandal-ridden terms and suffering from a bad economy, the country seemed ready for a change in 1876. Faced with popular demand for reform, both parties' bosses felt compelled to pick reformist candidates whom they did not like. The Democratic Party bosses nominated Samuel Tilden, reformist governor of New York, who'd fought against Tammany Hall, New York's Democratic Party machine. The Republican Party bosses picked a three-term governor from the vital swing state of Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes, whom they disliked for sabotaging their preferred candidate but needed because of his reformist image. Hayes cut a deal with the bosses that, if elected, he would retire after a single term--so that next time they could nominate someone they liked better, once this reformist thing had blown over.

Then each candidate sat back and let the boys do what they had to do to get him elected.

By manipulating immigrants, increasing government payrolls and requiring employees to pay kickbacks, the political bosses had become enormously powerful and arrogant. The Civil War had proven that victory goes to the most ruthless, and in 1876 supporters of both candidates tried to steal the election.

On election night, Tilden polled 250,000 more votes than Hayes, and Tilden would end up winning 51 percent to Hayes' 48. More importantly in our peculiar system, Tilden appeared to be way ahead in electoral votes (203 to 166). But late on election night, the editors of The New York Times, at that time a Republican newspaper, heard that the Democrats were less than confident that they had won Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina--all still under Reconstruction rule and Republican governors. So the Times editors crunched a few numbers and figured out that if those states' 19 electoral votes somehow ended up in the Hayes column instead, then Hayes would win by one electoral vote, 185-184. They decided to make it happen.

Despite all indications that those three Southern states' votes had gone to Tilden, the Times contradicted the rest of the press and proclaimed that Hayes had won South Carolina and Louisiana, with Florida still in doubt. And here's where the modern parallels start to get spooky, because the subsequent thefts of Florida's, South Carolina's and Louisiana's electoral votes were tied to systematic efforts to prevent African Americans (likely Republican voters) from voting. The resurgent Southern whites used various methods, including Ku Klux Klan terrorism, to stop blacks from voting and to disqualify or deep-six the votes of those who did. Meanwhile, the carpetbaggers (Northern opportunists in league with the Republicans) who had controlled those state governments since the end of the war made every effort to disqualify Southern whites (likely Democratic voters).

Under Reconstruction, the three states' election results were certified by returning boards, and these were controlled by the three Republican governors. The returning boards could invalidate the votes of a whole district if it were proven that even one African American (male) had been prevented from voting. And a whole lot of that had happened. (Although all three states had black majorities, more whites cast votes.) So the returning boards in all three states, under enormous pressure from the political bosses, managed to throw out many thousands of white (mostly Democratic) votes, enough to switch Louisiana's, South Carolina's and Florida's electoral votes from Tilden's column to Hayes'.

In the end, both sides submitted slates of electors that they claimed were the rightful winners in those three states.

Under the Constitution, the electoral college votes are counted in the presence of Congress, but the founders neglected to say who does the counting. It happened that the Senate was controlled by the Republicans but the House of Representatives had just been taken over by the Democrats. Owing to the lack of clarity in the Constitution as to exactly how Congress was expected to resolve such a dispute, the Republican Senate and the Democratic House agreed to set up a 15-member commission to sort it all out. The commission included five senators, five House members and five Supreme Court justices. Four justices, two from each party, were expected to choose the independent Justice David Davis for the other seat. This would mean the commission consisted of seven Democrats and seven Republicans, plus one independent. All of a sudden, Davis found himself appointed by the Illinois state legislature to serve in the U.S. Senate. So instead, the four justices picked a Republican, Justice Joseph Bradley, considered the most independent justice left to choose from, to take the 15th seat on the commission. With so much at stake, Joe Bradley came under quite a bit of pressure. He had written an opinion favoring the Democrats in Florida, but changed his mind after a late-night visit from a couple of GOP leaders. In the end, Bradley voted with the Republicans at every opportunity. So the commission repeatedly voted 8-7 not to "go behind the returns," that is, not to investigate the official, Republican-governor-controlled counts in the disputed states. Thus they delivered Florida's, South Carolina's and Louisiana's combined 19 electoral votes to Hayes, who won the electoral college by a vote of 185-184--though he lost the popular vote by a quarter-million votes, or 48 percent to Tilden's 51 percent.

Unlike Al Gore and friends in 2000, who accepted the Supreme Court's blatantly partisan 5-4 theft with disappointing docility, Tilden refused to roll over to the commission's blatantly partisan 8-7 theft and Tilden's supporters seriously threatened armed insurrection. Hayes' inauguration was greeted with hostile chants of "8 to 7," and history still recalls his popular nickname, "Rutherfraud B. Hayes."

Watergate: The Prequel

They say the first election you steal is the hardest, and once the Republicans had managed to steal the election of 1876 outright, they did it regularly;

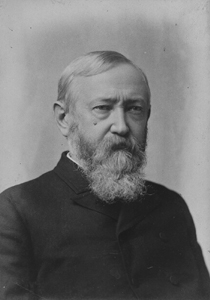

The year 1888 was the third time in the 19th century that the candidate who received the most popular votes lost the election and was also the first presidential election decided by a dirty trick.

When Benjamin Harrison heard he had been elected, he supposedly said, "Providence has given us the victory"--prompting a Republican party boss to retort that Harrison "ought to know that Providence hadn't a damn thing to do with it."

The Democrats finally won an election when Grover Cleveland captured the White House in 1884. By 1888, the Republicans were seething to recapture the presidency. Both elections would be decided by the electoral votes of New York, depending on which way the Irish immigrant vote tipped.

So by 1888, the Republicans set their sights on the Irish immigrant voters of New York. There was a very touchy treaty dispute going on between the U.S. and Canada, then still a British dominion, a crisis which President Cleveland had managed to finesse to his political advantage, making the Republicans in Congress appear pro-British, thereby making those Irish inclined to vote for Cleveland, the Democrat. But before the election, a man claiming to be a transplanted Brit now living in California wrote and asked the British ambassador to the U.S. which presidential candidate he considered better for the interests of Great Britain. The ambassador wrote back that he thought President Cleveland was better for Britain. Pro-British meant anti-Irish, and after the ambassador's letter got out, the Irish flocked to Harrison's side. So he carried New York, captured a majority in the electoral college and moved into the White House. Just a couple of problems: He actually lost the popular vote by 90,000 votes (47.8 percent to 48.6 percent). And it turned out that the Brit expat who wrote the letter to the British consul wasn't a Brit after all--he was a California Republican activist.

Here again, we see that to win the White House when most voters expressly prefer someone else, one must cheat. And here again, we see that the American populace, while allowing the candidate who wins through dishonesty to take office, still did not forgive or forget, but voted the guy out at the next regular opportunity. In 1892 the American electorate ousted Harrison and reinstalled Cleveland in the White House.

Miami Vice 2

So the pattern has been consistent: popular-vote losers who finagle their way into the White House once don't get a second term.

And this brings us to George W. Bush. Not only did he lose the popular vote in 2000 to Democrat Al Gore by a half-million votes (or a half-percent), he also obtained Florida's pivotal electoral votes through fraud. There are many things wrong with the 2000 election, but they fall into two main categories: crimes committed in Florida by Gov. Jeb Bush, Secretary of State Katherine Harris and Co. that messed up the voting and vote-counting to help candidate Bush, and crimes committed in Washington by the five Republican members of the U.S. Supreme Court to whitewash the aforementioned crimes in Florida and award Bush the White House.

Florida is the only state ever to hire a private company (DBT Online, soon merged with ChoicePoint) with close Republican ties--to conduct the first stage of "cleansing" voter rolls. Acting on instructions from Republican Gov. Jeb Bush and Secretary of State Katherine Harris, and employing methods it has refused to disclose even to Florida's local election officials, ChoicePoint wrongfully removed the names of thousands legitimate voters--half of them African Americans, including hundreds obtained from a very wrong list of supposed ex-felons from Texas--yes, Gov. George Bush's Texas--and with many purges on bases like mismatched names. Later the company issued a "corrected" list--without actually correcting it. Bush and Harris used state agencies to track down many thousands of ex-felons who'd migrated from other states and took them off the voter rolls, despite the fact that Florida's courts, basing their ruling on Florida law and U.S. constitutional requirement that states accept other states' legal rulings ("the full faith and credit clause"), as Greg Palast writes in The Best Democracy Money Can Buy (page 36), "repeatedly told the governor he may not take away the civil rights of Florida citizens who have committed crimes in other states, served their time and had their rights restored." Jeb Bush ignored the courts and instructed Florida election officials to strike the voters' names anyway. These people were not allowed to vote. Half of this country's convicted felons are African American.

Attorney Vincent Bugliosi's book The Betrayal of America explains how five Republican-appointed U.S. Supreme Court justices (Rehnquist, Scalia, Thomas, O'Connor, Kennedy) deliberately prevented a full counting of votes in Florida so they could hand the election to the guy they wanted to pick their own successors--George W. Bush.

The justices' conflicts were several: Scalia, Thomas and their families had business and political connections to Bush, and O'Connor had told the Wall Street Journal that she wanted to retire soon but not if a Democratic president would be picking her replacement. None of these top jurists saw their ingrained biases as reason to recuse themselves from the case--on the contrary, they exhibited a great eagerness to wade in where no Supreme Court had gone before, and seize control of the people's election.

After the Florida Supreme Court ordered a manual recount to try and include the "undervotes" (ballots that had been officially discarded for technical reasons, including "hanging chads" and the like), as Gore was steadily cutting away at Bush's very thin lead the U.S. Supreme Court Five abruptly reversed the Florida Supreme Court and stopped the counting. Scalia wrote that counting these votes would violate George W. Bush's 14th Amendment right to "equal protection." Scalia declared that finding out who actually got the most votes would "threaten irreparable harm to petitioner [Bush] ... by casting a cloud upon what he claims to be the legitimacy of his election."

At least since 1945, the Supreme Court has always held that the equal protection clause only applies to a case where the discrimination was intentional, while Bush's side never even attempted to claim their candidate was the victim of intentional violation of his rights.

Another clue that the Supreme Court Five were up to no good is the false invocation of a Dec. 12 "deadline" for states to determine the winning slates of electors. Justice Stevens, in his dissent, points out: "In 1960, Hawaii appointed two slates of electors and Congress chose to count the one appointed on January 4, 1961." But hard facts like that didn't matter because the fix was already in for Bush.

Yes, in 2000, once again, the presidential election was stolen by the loser. And once again, in the wake of grand theft, many Americans harbor deep concerns about the survival of this democracy--about who owns the White House--even as Bush's four-year lease comes up for renewal.

Putting History to the Test

On historical grounds (without even going into his appalling record in office) George Bush Jr. can expect to get evicted after one term, just like his father, and just like the other popular-vote losers who weaseled their way into the White House.

But it would be naive to assume that the Bush gang will meekly submit to historical pattern and allow themselves to lose this one fair and square. They got away with stealing the election in 2000. As the Republican elite who discovered they could steal the presidential election in 1876 went right on to steal several more, so we can assume that the Republican elite who stole the election in 2000 will be emboldened and encouraged by that success.

Florida was the first state to adopt "touch screen" voting, which is very vulnerable to wholesale fraud. With no paper trail, there'll be no fights over recounts because there's nothing to recount. In 2004 there is an urgent need to fight for a full and fair count.

But do Americans in the 21st century still have the brass to stand up to the people in power? In 1876 Tilden supporters were on the edge of armed rebellion. By contrast, in 2000 when the Supreme Court Five handed it to Bush, Al Gore, his attorneys and the entire Democratic Party establishment threw in the towel. Nobody dared to push the challenge any further, to exact concessions as Tilden supporters did. But Americans still cherish the right to choose our own leaders. And--to borrow Dubya's favorite phrase--those who oppose democracy will be brought to justice.

Election Day is Nov. 2.

[ Santa Cruz | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

Adams' Rob: John Quincy Adams was the first president to get into the White House by means of backroom deals rather than by winning the popular vote. But he wasn't the last.

It's All About the Benjamin : Benjamin Harrison lost the popular vote to Grover Cleveland in 1888 by 90,000 ballots. But Harrison won the electoral battle thanks to a fraud perpetrated to manipulate the immigrant vote in New York. In 1892, his re-election campaign was ixnayed by voters, who reinstalled pre-scandal favorite Cleveland.

From the June 30-July 7, 2004 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.