![[MetroActive Stage]](/gifs/stage468.gif)

[ Stage Index | Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Playing and Nothingness

In 'Kean,' busy postmodernism

wins out over wit and eloquence

By Christina Waters

JEAN-PAUL SARTRE, existentialist, Nobel Prize refusé and darling of postwar bohemians, wrote--infamously--that man is a useless passion. While the phrase has become a cliche, its true meaning--that we can never be anything and hence are condemned to merely play at being something--fuels the current Shakespeare Santa Cruz production of Sartre's Kean. Mounted around the substantial talents of artistic director Paul Whitworth--a lifelong actor playing a lifelong actor--the play is Sartre's deliciously eloquent redux of an Alexandre Dumas play.

The Kean in question was indeed a real actor--a phrase Sartre would relish; in fact he was the greatest actor of his early-19th-century heyday, a wiry former acrobat whose Shakespearean repertoire was small but apparently astonishing. A tireless drinker and philanderer, the actor was eventually forced to flee England on the heels of a scandal involving a politician's wife, a scenario that fuels one of the play's main themes. Kean's interpretations of parts like Shylock, Othello and Richard III so knocked the socks off his contemporaries that no less a luminary than Coleridge confessed that "to see Kean act is like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning."

The same could be said for Whitworth, who after 14 seasons with this festival increasingly carries its most polished moments on his seasoned shoulders. And he plows into this role with bravura and brilliance, often--when direction allows--savoring Sartre's ironic word play and the backstage realities of a profession devoted to illusion.

The best moments occur when the deep subtext reveals itself. In mock despair--according to Sartre, all emotions are merely performance pieces--Kean proceeds to drink himself into a lather moments before he has to go onstage as a Shakespearean hero. Watching Whitworth the actor transform Kean the man into Kean the actor playing Romeo is sheer--and of course this is the point--magic.

Today's media-saturated audiences are aware of actors' identity issues--examples abound of players whose very existence is seemingly created though their role du jour; Peter Sellers, Robin Williams, Jim Carrey. Yet Kean provides fresh and delightful examples of the tension between the private man--Kean who just wants to be in love--and the public matinee idol over whom bored countesses wish to swoon.

PART BITING COMMENTARY on our inability to avoid play-acting, part bedroom farce, this production of Kean is compromised by many unfortunate decisions. The casting is uneven. While the poised Ursula Meyer and Lise Bruneau spend woefully few moments onstage--kudos to costume designer David Zinn for the great red dress--the painfully awkward Natalie Griffith is all too present. Griffith's ugly attire is proof that Zinn has bad days too, but her amateurish hand gestures are hers and director Michael Edwards' responsibility.

Tumblers frolic in acid-neon tights between acts, like Victorian Cirque du Soleil players. While a diverting way of hiding scene changes, they are too distracting and destructive of the play's mood. It's as if the production creators didn't trust the audience to stay awake without huge helpings of eye candy.

Edwards seems also to disrespect the play itself, insisting on making romp rather than reflection the default position of every scene--turning Sartre into Shaw. What's trivialized is the spark and mordant power of Sartre's insights on role-playing, about how once we become identified with a certain role--be it a Shakespearean character, or wife, husband, politician--the world around us won't let us stop playing the part.

By the end of the production, Whitworth--undermatched by all but the hale and hearty performance of Bryan Torfeh as Kean's fellow carouser the Prince of Wales--seems as exhausted as we are. There's a difference between playing a part and carrying the play. We feel exhausted watching one player maintain the energy and momentum being dropped all around him. Most of the time, Whitworth appears to be the only living being on stage.

Thanks to Whitworth's intelligent reading, there is some real behind-the-scenes magic--the true stuff of stagecraft--in this three-hour production. Two scenes stand out. In one we watch as Whitworth/Kean begins to apply blackface for Kean's benefit performance of the last act of Othello, all the while complaining to his butler Solomon (played absently by W. Francis Walters) about some romantic rendezvous gone wrong. Whitworth furiously applies greasepaint, straps on a sword, steps into royal robes and dons a black wig--still talking, gesturing, in constant motion. Suddenly, magically, it is Othello who stands before us--or rather Whitworth playing Kean playing Othello.

In the death scene from Othello that follows, Whitworth treats us to some of the melodramatic stances, poses and acting styles of the mid&-19th century. We truly believe in this mirage of time-travel. Whitworth dissolves, and Edmund Kean takes the stage. Just like real life, as Sartre would say--it's only make-believe.

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

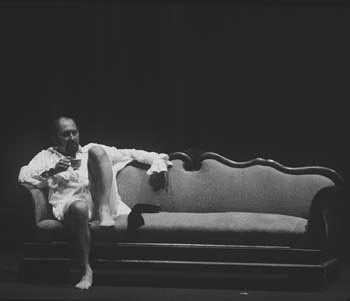

One-Man Band: As leading 19th-century actor Edmund Kean, Paul Whitworth carries most of the cast and still manages to deliver great moments despite noisy direction.

Kean plays Tuesdays to Sundays at various times through Aug. 26. Mainstage, Theater Arts Center, UCSC, Santa Cruz. $6&-$32. (459.2159)

From the August 2-9, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.