![[Metroactive Books]](/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Premature Illumination

Robert Anton Wilson, the iconoclastic genius behind the famed 'Illuminatus! Trilogy,' has a few thousand things he'd like to teach you

By Bill Forman

Decades before the crossover cult film What the Bleep Do We Know!? popularized the idea that the principles of quantum mechanics could be applied to the world at large, Robert Anton Wilson had laid out much the same theory in his book, Prometheus Rising. Venture further into Wilson's oeuvre and you'll find equally prescient material on longevity research; you'll likely even stumble across source materials that inspired Dan Brown to write The DaVinci Code.

"I think I'm the most ripped-off artist of our time," says Wilson, seated in the living room of a modest Capitola apartment adorned with an array of pookahs, Buddhas and at least one Loch Ness monster. "People keep coming out with books 30 years after--books on things I wrote about--and they all become bestsellers.

"I wrote about them too early," says Wilson, raising a thin arm and shaking his finger to emphasize his point: "Don't be premature."

Lance Bauscher agrees. "This whole DaVinci Code thing with Dan Brown, I mean, that's all Bob's material," says Bauscher, who directed a film about Wilson called Maybe Logic and also runs an academy through which Wilson's online course, "Tale of the Tribe," begins on Aug. 14. "Dan Brown has read all of Bob's books. But Bob doesn't really compromise his storytelling--not that Dan Brown does--but it's for a general audience, and Bob just doesn't go there."

Maybe that's because Wilson can't helping throwing his audiences so many curve balls, mixing esoteric facts with wild flights of imagination--and rarely revealing which is which. From self-destructing mynah birds to world domination enterprises determined to grant immortality to Adolf Hitler, the irascible Wilson's Illuminatus! Trilogy (written in the '70s with co-author Robert Shea) is a fun-house ride through every conspiracy theory under the sun--as well as a few that appear to have been hatched in some far distant solar system.

At age 73, Wilson's body and voice have both been weakened by post-polio syndrome, but his brain and his humor are as sharp as ever.

"His humor is constant and people are never sure if he's being serious," says Bauscher of Wilson's intellectual gymnastics. "I mean, the Illuminati: is it a joke or serious? And Discordianism: is it a joke disguised as a religion, or a religion disguised as a joke?"

All of which helps explain why Wilson's name doesn't frequent bestseller lists, nor is he routinely credited for the insights that are beginning to capture the public imagination decades later.

In fact, one day this past spring, after Santa Cruz moviegoers had lined up to see What the Bleep Do We Know!? in sufficient numbers to justify its three-month run, Robert Anton Wilson was lying alone, conscious but unable to move, on the floor of this one-bedroom Capitola apartment for 30 hours.

"It really didn't seem that long," says Wilson of his collapse, which ended when his daughter arrived and broke down the door. "And I remember thinking, as I'm lying there trying to move and unable to move: Hey, I may be dying now. And it didn't frighten me or bother me at all."

Wilson's subsequent trip to the hospital, the first of his adult life, was a different story altogether.

"The worst thing about hospitals," says Wilson, who was rescued when his daughter managed to break into the apartment, "is that all the rights guaranteed in the first 10 amendments are immediately canceled. You have no civil rights whatsoever. And the second thing is, all the ordinary rules no longer apply--you are no longer a person deserving of kindness, you're a disobedient child who has to be reprimanded and herded around. My God, I don't know why people put up with such treatment."

Wilson, we can presume, doesn't particularly like being told what to do.

"Not by people who treat me like an idiot. Not when I'm 73 years old, I have 35 books in print, I supported a wife and four kids for most of my life. I do not appreciate being treated like a disobedient 4-year-old, the way they treat everybody in the hospital."

Of course, you don't have to go to a hospital to be treated like that, but Wilson's on a roll ...

"I was an editor of Playboy, for chrissake," he cries, as though that, if nothing else, should carry some weight in this culture. "I've had plays performed in England, Germany and the United States; my books are in print in a dozen countries. Why the hell do they treat me like a child? I refuse to tolerate it. If they won't treat me with dignity, I won't go anywhere near them, especially with all the goddamned germs they got floating around there. CNN did a report on it--the number of people who are killed by diseases picked up in hospitals is much greater than the number who are killed by cars.

"I'm never going to a hospital again. Never, never, never, never! I will lie on the floor and die before I go back to a hospital."

R.A.W. Power: Despite post-polio symptoms, Wilson hasn't lost his edge.

Maybe, Baby

A presumably less opinionated Robert Anton Wilson was born into this world--Brooklyn or Long Island, he claims not to remember which--on Jan. 18, 1932. Raised in an Irish-Catholic ghetto, he attended a Catholic school whose strict dogma and not exactly cheerful nuns helped inspire future rebellions. When he was 7 or 8, Wilson recalls in Bauscher's film, they told him there was no Santa Claus.

"I kept waiting for them to admit there's no God," says Wilson. "They never did."

Wilson attributes the curing of his childhood case of polio at the age of 4 to the Sister Kenny method of physical therapy, which in those days was regarded by the medical community as so much quackery.

Such formative events left Wilson with a high regard for experimentation and research, as well as a decided antipathy for faith-based and conventional wisdom.

"Faith-based organizations say we don't need any more research, we know enough now, we can be dogmatic, whereas researchers say we don't know enough now, investigate, research," argues Wilson. "Faith is a reason to become stupid: 'From this point forward, I will remain stupid.' To me, faith-based organizations are responsible for everything I see wrong with this planet. Research-based organizations are responsible for everything I like about it. Before the French Revolution, the average life expectancy was 37 years. Now it's 78 years. All due to research-based organizations. Not at all due to faith-based organizations. All faith-based organizations give you is George Bush. Research-based organizations give you cures for disease."

At age 17, Wilson was planning a career in electrical engineering when he came across a copy of Alfred Korzybski's Science and Sanity while perusing the library bookshelves at Brooklyn Technical High School. Korzybski--who will be featured in the "Tale of the Tribe" class along with other seminal thinkers like Giordano Bruno, Giambatista Vico, Friederich Nietzsche, Ernest Fenollosa, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Buckminster Fuller, Claude Shannon and Marshall McLuhan--had as profound an influence on Wilson's young mind as his work would have on that of later generations.

Wilson was particularly taken with the Polish semanticist's critique of newer European languages. "Korzybski suggested dozens of reforms in our speech and our writings, most of which I try to follow. One of them is if people said 'maybe' more often, the world would suddenly become stark, staring sane. Can you see Jerry Falwell saying: "Maybe God hates gay people. Maybe Jesus is the son of God.' Every muezzin in Islam resounding at night in booming voices: 'There is no God except maybe Allah. And maybe Mohammed is his prophet. Think about how sane the world would become after a while."

Maybe it would.

"Well, yeah," says Wilson. "Maybe."

Some of It Has Got to Be True

The opening of the American mind, or at least the one belonging to Robert Anton Wilson, continued more-or-less unabated throughout the '50s and '60s. In 1958, he married Arlen Riley--who had worked as a scriptwriter for an Orson Welles radio show--and she went on to introduce Wilson to the work of Alan Watts. Friendship and collaborations with Timothy Leary followed, as well as experimentation with an array of drugs and mystic traditions. But it was in the decidedly secular surroundings of the Playboy editorial office, back in the late '60s, that two associate editors would hatch the idea of the Illuminatus! Trilogy, which remains Wilson's best-known work to this day.

"I'm sorry to disappoint you, but it was much like working at any other magazine," says Wilson, who never even got to visit Hef's grotto. "I mean, you went into the office, you did your job and you went home. The difference is that all the girls were good-looking. Of course, I was happily married and not fucking all the secretaries, I'm sorry to say."

Wilson and co-conspirator Robert Shea did borrow a few ideas from letters to the editor they received at Playboy, but most of the influence on their collaboration came from the broader gestalt of an era that was obsessed with esoteric arcana and increasingly paranoid about all manner of conspiracies.

"He and I were talking one night over bloody marys and peanuts," recalls Wilson, "and he says, 'What if every conspiracy theory is true?' It began as satire, but a lot of people were really scared by it. Which makes sense, because some of it has got to be true."

Careening wildly from detective story to first-person rant, from twisted history to apocryphal speculation, the Illuminatus works continue to influence the oddest assortment of young minds. Camper Van Beethoven were outspoken fans, as were the Seattle Posies, who paid tribute to Wilson on their first album. (Wilson says Guns 'N' Roses were also fans, but it's probably unfair to hold him responsible for them,) Author Tom Robbins is a Wilson devotee, as is Bay Area author R.U. Sirius, who took his name from Wilson's book, Cosmic Triggers, and went on to found Wired magazine precursor Mondo 2000. (Sirius is also one of the instructors at the Maybe Logic online academy, as are Dice Man author Luke Rhinehart; chaos magic godfather Peter Carroll; DePaul professor Patricia Monahan, who is also Robert Shea's widow; and several others.)

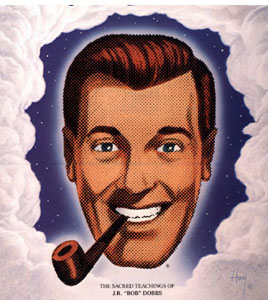

Wilson has also inspired at least two religions, or send-ups thereof: Discordianism took root in the immediate wake of the trilogy, while the Church of the Subgenius enshrined Wilson--in the form of pipe-clenching icon Bob Dobbs--as its figurehead some two decades later.

While introducing him at a convention, Subgenius founder and high priest Ivor Stang called Wilson "the Carl Sagan of religion, the Jerry Falwell of quantum physics, the Arnold Schwarzenegger of feminism" and "the James Joyce of swingset assembly manuals."

As the years went on, Wilson continued to write and speak with relentless energy. After he and his wife moved up to Capitola in the early '90s, he used an early incident here as a way to explain quantum physics.

"When I moved from Los Angeles I moved into what I thought was Santa Cruz," Wilson told a European audience during footage included in Bauscher's film. "Then we had something stolen from our car and we called the police, and it turned out we didn't live in Santa Cruz, we lived in a town called Capitola. The post office thought we lived in Santa Cruz, the police thought we lived in Capitola. I started investigating this and a reporter at the local newspaper told me we didn't live in Santa Cruz or Capitola, we lived in a unincorporated area called Live Oak."

"Now quantum mechanics is just like that," Wilson continues, "except that in the case of Santa Cruz, Capitola and Live Oak, we don't get too confused because we remember we invented the lines on the map. But quantum physics seems confusing because a lot of people think we didn't invent the lines, so it seems hard to understand how a particle can be in three places at the same time and not be anywhere at all."

The League of Armed Marijuana Patients

After 41 years of marriage, Wilson's wife and co-conspirator, Arlen, passed away in 1999, leaving Robert to continue on his own. The onset of post-polio symptoms has all but eliminated his speaking engagements, while making him a fervent proponent of the medical marijuana movement. "I'm a member of WAMM [Wo/Man's Alliance for Medical Marijuana] and of LAMP," says Wilson. "LAMP is the League of Armed Marijuana Patients. And also the Guns & Dope Party."

It was under the auspices of the latter party that Wilson ran as a write-in alternative to Arnold Schwarzenegger in the recall election, putting forth a platform that included the replacement of capitol legislators with ostriches.

More seriously, he made a rare public appearance at a medical marijuana rally in Sacramento last month. "You know, at that WAMM rally the week before last, I was sitting up there and thinking, suppose some right-wing nut gets in and throws a bomb? Well, what the hell, I'd rather die for a cause then die for nothing. It didn't bother me at all. I can't frighten myself anymore."

But he can tire himself out. Not only is Wilson's mobility limited by post-polio symptoms, they also make him experience temperatures as 20 to 40 degrees colder than they actually are. "I was bitching to Lance about how post-polio problems are making it harder and harder to lecture, and he said, 'Well, why don't you start teaching online?'

"I enjoy feedback," says Wilson. "Intelligence is function of feedback. The more feedback you get, the more intelligent you become. The less feedback you get, the stupider you become."

Now, Wilson can use his iMac to communicate with the world outside--including students, fans and colleagues. Among the latter category are people like Albert Hoffman, the inventor of LSD as well as a drug called Hydergine, which Wilson describes as his "current panacea."

"It's a dendrite stimulant," explains Wilson. "Your nervous system has more dendrites than muscles. I may be walking naturally again someday if it works as well as some claim. Albert Hoffman is going to have his 100th birthday in January after 25 years on Hydergine, and everybody says he looks as healthy as a 60-year-old."

Through the years, Wilson and Hoffman have stayed in touch. "He's a fan of my books," says Wilson, "and I'm a fan of his drugs."

Yes, but Are You Serious?

In spite of his physical infirmity, Wilson is extremely generous with both his time and his wisdom. Still, even after hours of conversation, there remains one mystery he has yet to address. Maybe it's like asking a magician to give away the tricks of his trade, but when exactly is Wilson kidding and when is he, you know, serious?

The question causes Wilson to pause for the first time in our conversation, and then--is it by chance or conspiracy?--his phone rings.

The caller asks for Arlen Wilson, wanting to know if "he" is available to come to the phone. Wilson says no, and the caller asks to whom she's speaking.

"This is Boris Karloff," says Wilson.

"I'm sorry," says the caller, "did you say Boris Karloff?"

"Yes, what can I do for you?"

"Is Mr. Wilson available?"

"No, he moved to Shanghai a few years ago."

The phone conversation comes to an abrupt end shortly thereafter.

A telemarketer? I ask.

No, jury duty, he answers.

OK, so at what point is Wilson kidding and at what point is he serious?

"The older I get, the less seriously I take anything," says Wilson. "The Chinese say the wise become Confucian in good times, Buddhist in bad times and Taoist in old age. I'm old enough to be a Taoist. I don't see anything very seriously."

Not even, as it turns out, mortality.

"I know I'm going to die sometime soon: five weeks, five months, five years," says Wilson. "I don't know, maybe 50 years if stem cell research moves along. But I don't know and I don't care. And I can't take it seriously anymore. If George Bush is president of the free world, who can take anything seriously?

[ Santa Cruz | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

The Original Slacker: Wilson was the model and inspiration for the Church of the Subgenius and its iconic figurehead J.R. 'Bob' Dobbs.

Photograph by Dina Scoppettone

For more information on Robert Anton Wilson and links to his course, visit www.rawilson.com.

From the August 10-17, 2005 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.