![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

The Tubular Belle

Stepsister to the 'real' arts, TV is experiencing its Golden Age and has outstripped its showbiz siblings in style and substance

By Eric Johnson

THE AD EXECS AT ABC HAVE adopted a risky strategy to hype this year's new fall lineup. On the small screen and on billboards and bus posters from Madison Avenue to Hollywood Boulevard, ABC encourages TV-watchers to poke fun at themselves. "Hobbies, Schmobbies," the ads say. "Imagine Living in a No-TV Nation." The message, packed in double-reverse irony, being: Why do anything but watch TV?

This industry-cultivated message is engaged in a street fight with the most popular bumper sticker in America (behind the all-time classic "Skateboarding Is Not A Crime," and just ahead of "Imagine Whirled Peas," which reads: "Kill Your Television." This is a militant expression of a deadly earnest sentiment shared, to one degree of another, by smartypants people everywhere: Television is a bad, dangerous habit. Turning on that machine will turn you into an idiot. It will suck you in and rot your brain. Just Say No.

This demonization has been so complete, even people who still watch (which means 95 percent of us) do so with a guilty conscience. We know we should be reading, going on evening walks, having long talks with our teenagers. But instead we sit there, half-ashamed, cracking up (again) at Jerry and Elaine as they debate whether they should go to the diner or do something meaningful.

This is sick. There's something twisted about 60 million people agreeing that a thing is bad and then doing it anyway, or renouncing a harmless pleasure because they've fallen for some quasi-religious belief that a bad book is better than a good episode of ER.

This kind of repressive self-flagellation was supposed to have gone out with the Age of Reason. It feeds deep psychological alienation, telling us to ignore what we feel in favor of what we think we should feel. Worse than that, it could make us miss some really great shows.

Ultimate Art Form

TRY THIS AT A PARTY. Find a group of people talking about movies (they're probably standing around in the kitchen). After you've heard someone remark with despair that Sean Penn was a letdown in She's So Lovely, and another opine that Stallone's bulked-up performance in Copland was inspired by the Gods of Method, Keitel and DeNiro, pipe in with some serious thoughts on The Full Monty, just so the film buffs will know you're one of them.

Then ask what they think about George Segal's performance on Just Shoot Me (NBC, 9:30pm Tuesday).

They'll look at you like you just farted.

C'mon, we're talking George Segal. Didn't they love him in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Of course they did.

Did they see him in the excellent 1996 Ben Stiller-directed Flirting With Disaster?

Oh, yeah, he was great in that.

On Just Shoot Me, Segal plays the publisher of a glamour mag called Blush, whose daughter (played by the superb Laura San Giacomo) goes to work for him. It's a smart little comedy, created by the guys who did The Larry Sanders Show and ... .

"Wait, hold up a minute," you'll be interrupted. "This is a party. And you're talking about television. That is so ... crass."

This is exactly the problem.

Talking intelligently about TV, in many circles, is verboten. It is a taboo subject. This, despite the fact that many television shows today are much better than most Hollywood movies, more relevant to our lives than the coolest Czechoslovakian import could ever hope to be and smarter than half of the American indie flicks playing at the Nickelodeon.

La Femme Nikita, about to embark on its second season on the USA Network, is a good example. The Luc Besson original, from which this is adapted, was of course a great movie. This is better. Produced by a small studio in Toronto, the TV La Femme uses a stylish mix-and-match pastiche of techniques--shot partly on film, partly on video--and the sets, camerawork and music are appropriately edgy.

The Hollywoodization of La Femme, titled No Way Out, was also surprisingly good, largely because of Bridget Fonda's interpretation of Nikita.

TV's Peta Wilson, however, is the best Nikita ever. With her, the kickboxing babe-with-a-gun thing reaches its full erotic potential.

The real networks are stocked with eminently watchable fare as well. Homicide: Life on the Streets, at its best, is as good as any police movie to come along in years.

For human drama, the same can be said for ER, NYPD Blue and Law & Order.

For imagination and creativity, The X-Files rules in the place once inhabited by Twin Peaks--which was better than any of director David Lynch's movies.

And then there's Seinfeld, the greatest TV comedy of all time. While even the TV-bashing snobs will concede that in the old days TV was great, it's a fact that Seinfeld has been funnier longer than The Honeymooners, I Love Lucy, The Dick Van Dyke Show and MASH combined.

This is the Golden Age of Television.

Growing Concerns

MORE THAN ANY ART FORM since tribal storytellers held forth nightly around the campfire, television allows plotlines to evolve over time. A well-drawn character like NYPD Blue's Sgt. Andy Sipowicz (Dennis Franz) or Homicide's Detective Pembleton (Andre Braugher) can develop and grow over the weeks of one season and from year to year.

This allows audiences to get to know these characters over time and to learn things about the world and themselves through these characters' lives.

Because TV brings its stories directly into viewers' homes, the end result of this capacity for engagement can be deeply political.

When Vice President Dan Quayle attacked Candice Bergen's Murphy Brown for deciding to have a child out of wedlock, he recognized two things that many among his countrymen still haven't figured out. One was that the political capital of the nation had shifted from Washington, D.C., to the world inside our television sets. The other was that TV-land was becoming a very liberal place.

Now, Murphy's been left in the ideological dust. From Ellen's celebrated queerness to Cybill's happily fractured family, TV today is beginning to reflect our fun-house-mirror multiculture, a progressive place where people get to be exactly who they want to be.

According to the age-old criticism, it makes no difference how free the characters on TV are when the nation's real institutions of power remain closed and inaccessible.

That is true enough, but then, TV happens to be among the most powerful institutions in the nation. For the young lesbian hounded in high school, it might feel important that Ellen is still loved after coming out. And I know that for my daughter, facing the teen horror of her parents' separation, it helped to see Cybill's TV-daughter Zoe cope with a similar situation.

Art has always served that function for people. The only qualitative difference between real art and popular art, in this regard, is that popular art does it for more people.

That scourge to elites is what makes TV the most democratic of art forms. While the bosses and their golf partners discuss the pleasures of the opera, the gang around the water cooler is talking about what Letterman did with a watermelon. And probably talking intelligently while they're cracking wise.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Fourplay: Elaine, Jerry, George and Kramer, collectively known as the cast of NBC's hit series 'Seinfeld,' enter their 10th--and some believe last--season of consistent wackiness and hare-brained schemes.

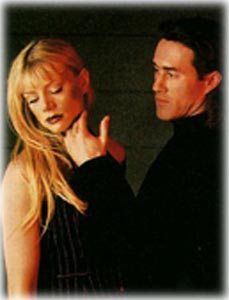

Border Crossings: Peta Wilson does her seductive, babe-with-a-gun best as television's edgy version of 'La Femme Nikita,' a Canadian product that pushes the censor envelope.

From the Sept. 18-24, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.