Good Home Hunting

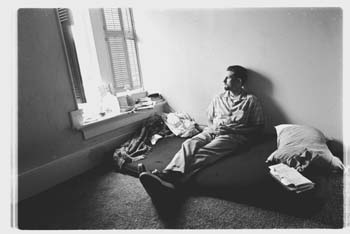

UCSC Spartans: Student Jeremy Rees makes do in typical student digs. Housing costs have skyrocketed in recent years.

Are the university, the county and developers doing enough to ease the Santa Cruz housing crunch?

By Kiersten McCutchan

THERE'S NO PLACE LIKE home. But if you're looking for a place to live in Santa Cruz, putting on Dorothy's ruby slippers and clicking your heels gets you nothing. Plain and simple, home-hunting in Santa Cruz sucks. It's a harrowing, brutal, dehumanizing rental market out there, especially if you've also got to move out of your old place in 30 days. If you have pets, kids or a less-than-immaculate credit history, or you're a student or barely getting by, forget it. Great references? No one cares. They don't have to. It's a seller's/landlord's market, and the biggest check wins.

We've all read the dismal comparisons of housing costs with the rest of the country, heard the stories of students camping in the redwoods, people living in tree stumps and the anguished accounts of landlords evicting decade-long tenants in favor of higher rents. Some landlords make outrageous demands: photos, self-invitations to see where you currently live and personality interviews. There are waiting lists and endless hours of phone calls that come to nothing. You promise yourself you'll clean up your credit act, maybe even finally find a better job. You make compromises. You rationalize. Maybe, you say, living with three other people won't be so bad after all, even if they do let the beer cans pile up like Mt. Everest, allow utilities to be turned off and don't know Mr. Clean from Mrs. Butterworth.

Finally, it's all you can afford to take a run-down studio, because you decide you can't cope with roommates anymore. You even consider sending your résumé to different parts of the country where rent is reasonable and buying a home someday is not the pie-in-the-sky notion it is here. But you know you're kidding yourself. This is Santa Cruz, and you could never live anywhere else. You and a lot of other people feel that way. And that, after all, is the problem.

The unforgiving economics of Silicon Valley have crept over the hill in the last few years, creating upward cost pressures on a local economy already burdened with low tourist-industry wages, student austerity and income disparities. Add to that a shortage of rental housing stock and an aversion to growth for environmental and other reasons, and you have a recipe for disaster. Being on the losing end of the real estate boom is a drag.

Motel Dorms

MOST DISCUSSIONS about the housing crunch begin with the influence of UCSC's student population. Elizabeth Irwin, director of public information for UCSC, acknowledges the criticism the school faces for the number of students it is enrolling. She says the university this fall expects to admit about 10,950. The campus can house 5,046 students in dorms, graduate facilities, trailers and family student housing. This includes 323 additional spaces this year that have been converted from other uses, such as student lounges, or by adding a third occupant to double rooms. Irwin says UCSC has the highest percentage of on-campus accommodations of any University of California campus.

Still, some students fall through the cracks. This fall, Carol Douglas-Hammer of the campus housing office expects about 435 students to be homeless and end up either sleeping on someone's couch or dropping out altogether.

Debates over campus housing policy have come and gone with expansion. In the early 1990s, when Colleges 9 and 10 were being planned, the university administration used extra housing as a justification for the expansion. Later, when Social Sciences buildings 1 and 2 were constructed in 1994 and 1995 as the centerpieces for the two colleges--and new housing didn't immediately follow--critics grumbled that the university had reneged on a promise.

But Irwin says the reason the housing wasn't built at the time was that from 1992 to 1995 the university experienced a period of declining enrollment. Now that the academic buildings have been finished and housing is needed, Irwin says the university will make up for lost time.

"We'll be breaking ground soon on the College 9 apartments," says Irwin. "The need and demand is definitely there." The new construction will be able to house about 200 students.

Irwin says the campus first felt the housing crunch in fall of 1996, when campus housing reached full capacity. She adds that the university plans to spend some $75 million on new housing in the next few years, adding over 1,600 beds. Although there are no reliable estimates of future enrollment, the new beds could end up providing housing for the lion's share of new enrollees.

UCSC has not entirely ignored its off-campus students. One effort started last year houses 176 students in local motels that offer rooms in the off-season for a comparable university dorm rate. Students get continental breakfast, cable, free local calls and weekly room cleaning. But the contracts are only for six months, so studies are often disrupted with new searches for housing. Another plan, to house students at California State University Monterey Bay fell through.

But many observers feel the university isn't doing enough. Bryan Briggs, a Santa Cruz County planning commissioner, calls the motel alternative "putting a Band-Aid on the problem," and says it is designed more to make the university appear to be dealing with the problem than to create more housing. The program's biggest accomplishment, he says, is to enrich the hotel owners during the slow season.

Most critics of university housing policies recognize that a lack of student housing is only part of the housing problem. According to Irwin and the state office of economic development, both the student and county populations have increased by about 9 percent since 1990. A more important reason for the housing crunch, most observers agree, is a familiar one: the fierce rental bidding war exacerbated by salaried workers moving in from Silicon Valley. University community rentals program coordinator Wanda Amos says she knows of one instance where an apartment received 200 applications, and only five of them were from students.

In addition to population increases and competition from Silicon Valley refugees, there is a third factor in creating the housing shortage. While there are no hard data, many industry observers believe there has been a decrease in the inventory of rental housing stock in recent years. Realtor Tom Brezsny of Monterey Bay Properties says a lot of first-time home buyers entered the market in 1994. Many houses that were formally rental properties were bought and removed from the rental market.

"Even now there are fewer and fewer available rentals" as people continue to purchase and occupy homes that were previously rentals, says Brezsny. Amos says her program has also experienced a dramatic decline--20 percent in the past five years--in available rental units.

Some critics believe the city of Santa Cruz could be doing a lot more to encourage building more multi-family structures, but that environmental politics have gotten in the way.

"The last few years the city wanted the kind of environment that was for single-family units," says Irwin. "The issue with multi-family unit housing is the responsibility of the government in a partnership appropriate for the community."

On this point, Irwin and Briggs agree. "The political climate and constraints set up by the City Council haven't been feasible for multi-family units," Briggs says. "Plus, most of the money being made has been made from single-family housing. Those two phenomena created a dearth in multi-family-unit housing."

Affordability Blues

INFORMATION ABOUT RATES of increase in residential rents in Santa Cruz County is almost entirely anecdotal. But discussions with several local Realtors and property management firms, including Brezsny and Linda Reid, a property manager at Sherman and Boone, suggest that rents in the broad market have gone up by as much as 50 percent in the last four years.

Rita Law, owner of Kendall and Potter Property Management, says the market "has never been so crazy." She says that while things have settled down in recent weeks, the most recent run-up in rental rates began around January. A normal year will see rental rate increases of about 5 percent, Law says, but since last fall she estimates rent increases have gone up as much as 25 percent in some cases.

Perhaps stating the obvious, Mark Deming, a principle planner for advance and resource planning for Santa Cruz County, puts things in perspective. "Two to three years ago you had your pick," says Deming. "Now everything in sight is being rented at unbelievable prices."

By comparison, Amos says her student referral program shows only single-digit percentage increases for various sizes of rentals over the last five years. This may be due, she says, to the type of listings that come to her office. Landlords looking for student tenants tend to offer only the most affordable units.

Georgann Russell, president of Remi Company, a local rental property management firm, contends that rents really haven't gone up so much. In fact, she say, they have only just recovered to the level, accounting for inflation, of where they would have been had the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake not depressed the local economy. For example, she says, a two-bedroom one-bath apartment in Capitola that rented for $1,100 before the quake would rent now for about $1,400. But the price of that unit dropped temporarily to around $950 after the quake.

The question of what is affordable is rather tricky. According to figures from the state Department of Economic Development, Santa Cruz County incomes tend to lag about 20 percent below neighboring Santa Clara County. Also, a gap between the median, or middle value, and the mean, or average, incomes suggest wider-than-average income disparities. That, in turn, supports the contention that, while not all students are poor, renters of widely divergent incomes compete for the same units.

One of the few sources of affordable housing in the county is known as Measure J, which was passed in 1978. A similar city ordinance known as Measure O passed in Santa Cruz the following year. Both measures sought to set limits on development and control growth. Both also had affordable housing components requiring that a percentage of new housing be stipulated as "affordable." Measure J required that 15 percent of all new residential construction involving five or more units or lots must be set aside as affordable housing.

Deming believes in Measure J. "We're very close to attaining that 15 percent goal.... The numbers since '79 have been high, over 14 percent--even if it's nowhere near what's really needed."

Cherry McCormick is the county housing coordinator who oversees the Measure J affordable housing program. She said the county has created some 600 units of affordable housing since 1981 with the help of the program. On the rental side, the maximum allowable Measure J rent is $793 for a two-bedroom apartment, which can be inhabited by up to three people earning a total of no more than $41,350 a year.

Unfortunately, Measure J hasn't provided much relief to renters: 80 percent of all eligible units are for-sale units, with price and eligibility restrictions. A family of four can make up to $70,450 a year and remain eligible to purchase an "affordable" Measure J house. A three-bedroom two-bath home in the program sells for $195,600--well below market rates, and yet still out of reach for most people.

Despite this, McCormick says, "I think the program has been very helpful."

Tapping the Feds

THERE ARE OTHER FUNDS and programs available from state and federal sources to help provide more low-income housing, but inertia has prevented the county from tapping those resources. Deming says one thing that has hurt the county is the lack of what is known as a "certified housing element."

Each county must review its general plan on a regular basis (usually every five years). The housing element is a part of this, which is then submitted to the state Department of Housing and Community Development for certification.

Certification makes the county eligible to apply for federal funds known as Community Development Block Grants, or CDBG money. Santa Cruz has not had a certified housing element for nearly a decade. The county was working on a new housing element when the Loma Prieta Earthquake hit in 1989. Ever since then, thanks to a series of delays and rejections of the plan it submitted, the county has been ineligible for these federal funds, which can be used for housing--although it has been able to get other funds, such as housing rehab loans.

Deming says the county is working toward certification of its housing element. "[The certified housing element] opens the door to state housing grants and federal programs," says Deming. "We're trying very hard to get it certified."

Not everyone thinks the county has been acting in good faith to get its housing element approved. Mary Thuerwachter, directing attorney for the Legal Aid Society of the Central Coast, said a lawsuit filed by the society charged that the county had failed to meet state requirements for low-income housing, contending the "housing element" lacked elements that would make the creation of affordable housing possible. The lawsuit was dismissed a few months ago on a technicality based on who was eligible to participate in the suit.

"No one wants affordable housing in their neighborhood, but we desperately need more affordable housing," Thuerwachter says. "The county's 'housing element' has done nothing to improve affordable housing since before 1989.

"There is really nothing out there for low- or very-low-income people. Most people who come to us spend two-thirds of their income on rent. The standard is supposed to be about 30 percent. That means if they make about $825 a month they spend $600 a month on rent. There's nothing left for food, utilities, anything." Thuerwachter is clearly disturbed. "It's very hard for low-income people here."

The Santa Cruz County Housing Authority, a nonprofit agency that provides a conduit for federally funded low-income housing, tries to fill the gap, but its resources are limited.

The biggest program the SCCHA administers, says Bill Raffo, SCCHA assistant director, is known as Section 8. This provides certificates or vouchers to low-income people who can then take them to the private market and use them to help pay their rent. The SCCHA also administers 234 units of public housing of its own, plus 70 units of year-round housing for migrant farm workers.

But if you're thinking about applying for one of those vouchers, think again. The county has about 2,000 vouchers available, with a waiting list of 6,500. The duration of the waiting list tends to vary from year to year. But even now, during a time when we are experiencing a strong, healthy economy, the wait is over six years.

"We try to bring as much federal money into the county as we can," says Deming, "but the federal well has been dry for the last five to six years. We've only been able to renew what we already had."

Rent Outta Control

UNDER THE CIRCUMSTANCES, some observers say the time is ripe for another shot at rent control in the city of Santa Cruz. Housing costs are spiraling out of control, progressive forces control the City Council and the percentage of renter/voters has increased dramatically in recent years. According to figures gathered from voter rolls by former Santa Cruz mayor Bruce Van Allen, the percentage of registered voters in the city who rent has risen from 53 percent in 1992 to 75 percent today. According to Van Allen, cities with around 80 percent renters have a good shot at passing rent control ordinances.

Attempts at rent control in Santa Cruz were made in 1978, 1979 and again in 1982, losing by bigger margins each time. Van Allen was a prominent rent control advocate in each of those elections. Today, he is cautious about making another attempt.

"Conditions certainly warrant it," says Van Allen. "The market is out of hand here. Government usually steps in and regulates when there are a large number of people being hurt by the market. That suggests a strong base of support."

Van Allen also knows that tenants are difficult to organize. "I wish there was a more active tenants movement here."

But there is an even bigger hurdle than reluctant tenants.

During the 1995-96 session the state legislature passed what is known as the Costa-Hawkins bill. The law essentially decontrols residential dwellings upon vacancy regardless of local ordinance and provides exemptions to rent control for all new construction and single-family residences. Thanks to Costa-Hawkins, there would not be much left to regulate.

Substandard Standards

SOMETIMES, FINDING a place is less of a problem than surviving in it. Student Jeremy Rees' experience was not unusual. He lived in a three-bedroom flat on Laurel Street with four other people. It had one bathroom, filthy carpet and kitchen, holes in the walls, a rotten stench and inadequate plumbing. He shared his room and paid $600 per month. Some such units are unknown to authorities. Santa Cruz City Councilmember Michael Rotkin says there may be as many as 2,000 to 3,000 "illegal" units on the market: converted garages, attics and basements that have not been reported to officials. In this economy, no one seems inclined to root out unreported scofflaws.

"Right now," says Briggs, "the market allows you to pay me $1,000 for a piece of junk." And yet minimum standards of liveability are "not generally defined," Rotkin says.

"There are health and safety codes that have to be met, like running water, safe electricity, plumbing," Rotkin says. "I don't know that it's written anywhere that you can't have a crack in the toilet seat."

Unlike some cities, Santa Cruz does not conduct regular housing inspections, but it does have two full-time code compliance specialists. Between the two they conduct an average of 30 to 40 inspections a month.

Linda Garner is one of them. She says she currently has 95 active cases, but calls 50 to 60 "manageable." City Council policy follows state law, which encourages tenants to work out problems first with their landlords. But Garner says the city will step in on its own in situations where the tenant has reason to fear retaliation for reporting problems. A city inspection application is confidential.

"The city will certainly start the process and check the unit," Garner says. "Some situations can be really difficult, because there are both irresponsible tenants and landlords. We enforce the uniform housing code, but we only deal with the bare minimum: lots of water heater problems, smoke detectors, windows. We only correct things that are broken. We don't go in and start requiring that everything that is substandard be brought up to code."

In the unincorporated areas of the county, the Department of Environmental Health is responsible for enforcing these codes. Like the city, the county has no regular inspection program. But unlike the city, the county has no full-time inspectors and only goes out on about a 100 calls a year. This is because county policies are tougher on tenants, and inspection requests often fall on deaf ears.

The county requires tenants to try to work out the problem in advance with landlords, and won't lift a finger to help until the tenant can document that a reasonable effort to do so has been made.

Diane Evans, director of the Department of Environmental Health, explains the policy.

"When a tenant calls we ask: have you given a legal notice to landlord? Most haven't done that. Frequently the tenant and landlord haven't communicated. Sometimes we are being called out of retaliation or frustration. Our policies ensure that only those cases that can't be resolved require us to get involved."

But Teresa Alvarado, a supervisor and a paralegal for the Legal Aid Society, condemns the county policy.

"It is not a responsible policy at all," Alvarado says.

One of the problems with the county's policy, she says, is that if a tenant who reports a problem is subjected to retaliation, he has no legal recourse until after he has been evicted.

"Once you've gotten that far, it's too late," Alvarado says. "The vast, vast majority of eviction cases end in eviction. That is why so many tenants shy away from reporting problems." The local Tenants Rights Union says it is pushing for a county ordinance that would require evictions to be arbitrated in advance.

Just Do It

MARY THUERWACHTER of Legal Aid likens the affordable housing situation to Samuel Clemens' comment about the weather: everyone talks about it, she says, but no one does anything about it. With UCSC students now scrambling for places to live, it seems an opportune time for public officials, developers and the public alike to do some soul-searching and ask themselves: What can be done to bring sanity back to the housing marketplace? How and where can new, affordable housing be built? It is the number one crisis facing Santa Cruz today, and yet the silence surrounding the issue is deafening.

"If somebody has money, they'll find a way to build [housing]," Thuerwachter says, "but that's not what's needed. We don't need to try to build more housing for San Jose commuters."

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

Taking Measures: County housing coordinator Cherry McCormick says Measure J has worked, but its success has been largely in the for-sale market, not rentals.

Hands-off Policy: Diane Evans, director of the county's Department of Environmental Health, says county policy is not to inspect problem housing units until after the tenant has complained to his landlord. Critics charge that this exposes the tenant to retaliation.

From the September 24-30, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)