![[MetroActive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

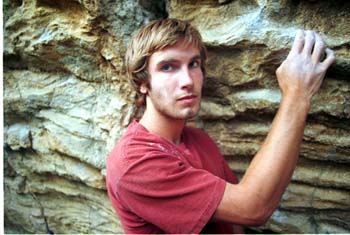

Zen and the Art of Climbing: Santa Cruz native Chris Sharma is redefining the limits of his sport: bouldering.

Rock Star

Forget hyped youth and extreme games, Chris Sharma defies gravity with grace

By Christa Fraser

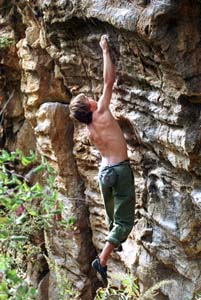

HE SWINGS HIS WEIGHT from dead still off a handhold the size of a truffle, becoming airborne. The instant his body is neither rising nor falling, he catches the next handhold, which is even smaller. The index and middle finger of his right hand lock on, and supporting his entire body weight by the two, he stops the pendulum motion of his body cold. The laws of gravity appear to be on hold.

Watching Chris Sharma climb rock is a lot like taking off in an airplane. The palms start to sweat while gravity tugs on the back. The mind measures how many feet of air exist between body and ground. When Chris reaches the top, the lungs exhale with the same sensation of relief as when the plane reaches cruising altitude.

At 19, the Santa Cruz native has already joined the pantheon of climbing legends. Not only is he winning climbing competitions by more than double the next highest score, as he did last April at the Phoenix Bouldering Competition--a subset of rock climbing held indoors or outdoors, on man-made or natural rock, where climbers scramble up boulders the size of a large house. He is also scoring first ascents on routes that have been attempted unsuccessfully by the best climbers in the world.

His grace and ability won him the gold medal for bouldering at last year's X Games in San Francisco, a competition held outdoors on man-made rock. The competition includes extreme sports such as Moto X, street luge and bicycle stunt riding.

The win helped propel Sharma into the role of one of America's latest "rock stars." In an era of advertising and media that uses images of young, hip athletes in positions that defy gravity, death and occasionally good sense to sell everything from cereal to sports utility vehicles, Chris Sharma is a rock climbing poster boy. He is good-looking, amicable and intelligent. He is ripped. He pulls gnarly moves. He shreds.

But Sharma is no young daredevil careening across television screens to staccato music while Newtonian physics take the day off. He comes across as humble and spiritual, an image that conflicts with that media stereotype.

Scaling Glass

HIS CLIMBING CAREER, surprisingly, began here in Santa Cruz, a place known more for grooming professional surfers and skateboarders than rock jocks. Nonetheless, at 11 years old he told his father, Bob Sharma, that he was going to grow up to be a professional rock climber.

"He started here at 12 years old," says Tom Davis, co-founder and co-owner of Pacific Edge Climbing Gym in Santa Cruz. "But by the end of the first year, we knew that he was something special."

Chris won the Bouldering Nationals in Phoenix, Ariz., at the age of 14, and the next year had nailed his first 5.14c-rated climb, which until recently was the ultimate level on the American rating system.

(Rating systems vary. The most widely recognized American system, which is used for both rock climbing and bouldering, runs from 5.1, an easy but vertical scramble, to 5.14, a level that few climbers hope to attain. Sublevels a through d indicate further levels of difficulty. The decimal point is tricky, because the number to the right of the decimal is not a fraction. Level 5.10, for example, follows 5.9.)

In addition to being famous and traveling the world in search of the perfect new route, he had an upbringing that in some respects seems to be a uniquely Santa Cruz experience.

Chris was born at home to Gita Jahn, a local masseuse and healing artist, and Bob Sharma, a maintenance supervisor at UCSC. His parents were married at Mt. Madonna Center. Babagi Hari Dass, the spiritual leader and founder of the center, gave them their last name of Sharma. He also gave Chris his middle name, Omprakash, which means "light of Brahma."

He earned his diploma at 15, freeing himself to travel in search of the newest rock. He has probably spent more time traveling than he has in a classroom, having been to Asia, New Zealand and Europe a number of times.

Sharma himself typically eschews naming or rating most climbs. He is more interested in talking about the nature of a climb than he is in discussing numbers or victories. Perhaps it is because both of his parents are lifelong students of Eastern traditions that Chris seems to have a Zen-like view of climbing.

"I love climbing. It's a great way to be in nature. It is moving on rock. It's not just a physical thing; it's also a spiritual thing ... where time stops. You stop thinking about stuff. There is no past, present or future. It all disintegrates."

"The thing that makes him so unique," Tom Davis says, "is that besides being exceptionally nice, he is completely unattached to the outcome of his every move. He is totally present with the move that he is doing. Normally, a person feels afraid to make a move. He goes for it without being afraid."

We're talking about moves that are typically executed 10 to 30 feet off the ground without a rope. For protection, climbing partners spot each other and line the fall zone with mattress pads. Nonetheless, a fall from a boulder problem can be as serious as a fall from a roped climb hundreds of feet off the ground.

Chris is pulling his body weight up rock on holds with the surface area of an M&M. At times, he even climbs smooth, overhanging rocks that have no real holds. The terms for these sorts of features and moves suggest pain and difficulty: crimpers, squeezes, slopers, pinches, lockouts and deadpoints. Brett Duryea, a longtime climber and former Santa Cruzan, likens what Chris does to "scaling a slightly chipped, overhanging piece of glass."

Photograph by George Sakkestad

The Mandala

FOR YEARS, BOULDERING was considered to be merely a type of training for climbing big walls, like El Capitan or Half Dome in Yosemite Valley. In the past decade, however, it has earned respect from the climbing community as a pursuit in and of itself while developing its own following.

The sport combines the athleticism of a gymnast, the flexibility of a yogi, the intellectual cunning of a chess player and the metaphysics of a mystic. Because it doesn't use the futuristic gear needed for higher climbs, bouldering is considered a pure endeavor. Aside from a pair of good climbing shoes and a bag of gymnast's chalk, it's just the climber and the rock.

Sharma says that of any sport he can think of besides running, it is the most natural. "You don't need a net, a racquet or a ball. There is no stuff. It's the most simple thing."

The routes that he is creating, however, are far from simple. His latest feat is a route on a large boulder in Bishop, Calif., where Chris has made his home for the last six months. The rock has been drawing climbers from all over the world for 20 years. Many have tried it, but no one had ever been able to complete the sequence of moves at the beginning to be successful, let alone do the rock in its entirety. Even Sharma believed it to be impossible when he first saw it.

"I have tried it for a period of a couple of years, and been over my head. I came back to it and it was still way over my head, then I came back to it and was feeling like I could possibly do it. Then I did it."

So inspired was he by that climb that, contrary to habit, he named it: The Mandala.

Naming a route is a privilege reserved for the first person to succeed on it. In keeping with the personalities who dominate the sport, recent first ascents in climbing tend to have names that, even in a locker room, might seem juvenile and mildly offensive. It is not uncommon to encounter names that accentuate the image that climbing has as an extreme, dangerous and edgy sport. Routes with names like Pestilence, Honky Serial Killer and Hydrophobia are common.

By contrast, writes Chris for The Bouldering Domain, a webzine, he chose the name because "a mandala is an object which explains, through its repetitive pattern, the universe's infinite nature. I feel a connection with the area that I have only been able to achieve through the constant familiarity and repetition of the same moves on the same problems."

If this is one of the poster boys for the X Games media generation, then at least one sport appears to be shifting away from the screaming, sweaty realm of the search for the ultimate adrenaline rush and into something akin to a pursuit of the transcendental. Chris is disparaging of extreme, death-defying takes on sports.

"That whole image is unreal. It's a good way to die, too," he says. "I don't know a lot of people who are like that in real life. It's a marketing gimmick."

No Mere Mortal

CHRIS, WHO IS SPONSORED by Prana, a climbing-clothing company, and 5.10, a climbing-shoe company, is savvy to the commercialism of his sport. His job definition is full-time climber. It's his business. He shows up for interviews and photo shoots wearing his sponsors' logos. He has been in several documentaries and climbing videos.

Yet the photos of Chris climbing show him practically levitating, concentrating his way up a rock. He could be a monk in prayer, or a man contemplating his next chess move. Whether he is a foot off the ground or 20 feet, a certain calm and poise mark his climbing.

These are not images that are going to sell a caffeine-laden drink or a sugary cereal, or encourage kids to go jump off a bridge. It contradicts that fiercely competitive and edgy media ploy, appearing instead to be an exercise in control and patience.

"Most people are battling with themselves more than with the rock," says Davis about Chris' climbing gift. "He doesn't have that." His focus and joy in what he does allow it to appear almost effortless. Even in competition, Chris doesn't seem to be battling with anything. He says that he enjoys competing because it helps him to focus.

Whether it is to say that a new climber was able to win because Chris didn't compete, or to tell readers about how everyone just enjoyed the competition because Chris earned so many points in the first go-round that no one else could hope to win, climbing reportage on competitions is incomplete without including Sharma's name, even in absentia. His achievements have become a standard by which the sport measures itself.

Here's the most frustrating part for the rest of us mortals: Chris doesn't really train. "I just climb. I probably should train. For me it's more mental, having the drive." He does, however, climb often.

He also enjoys teaching climbing to others. His friend Andy Puhvel gave him his first climbing lesson when he was 12. He now returns the favor by instructing at Puhvel and girlfriend Lisa Coleman's climbing school for kids, Yo! Basecamp. The school is held at various climbing locations in California.

New Risks

FOR NOW, CHRIS IS OFF to the south of France to attempt to climb two adjoining 5.14c routes sequentially. No one has been able to piece together the two routes, known as Biographique, in their entirety without pause, but Sharma may be the first. To do so he will use ropes, something he normally avoids. For those in the climbing world to whom difficulty ratings mean something, this could be the route that adds a 5.15 rating to the system, a level believed impossible to achieve before climbers like Chris came into the picture.

After his trip to France, Chris will head to Asia to visit several countries, including Thailand and Nepal. There he will meet up with his girlfriend, Julie de Jesus, a climber and writer for The Bouldering Domain, whom he met climbing in Tuolumne Meadows. During that time he plans to focus less on climbing and more on traveling and learning about the Eastern cultures that have been such a part of his upbringing.

When I ask Chris how he sees the future of rock climbing, he says that he sees it going toward "people doing it for themselves, for the spiritual aspect, enjoying nature and learning about themselves, not who is best."

It is also a sport that is moving into territory previously thought impossible, both physically and geographically. As rock climbing becomes a more mainstream pursuit, good climbers are being given the financial opportunities to uncover the next great climbing area. As a result, it is now more dangerous than ever--and not just in terms of the rating system. After what happened in Kyrghistan this August, climbers and adventurers in general have a new fear.

Tommy Caldwell and Beth Rodden, both famous young climbers (and friends of Chris) were kidnapped along with two other climbing companions. The climbers were several hundred feet up a climb when they realized the gunmen were shooting at them. They descended and were held captive for nearly a week, surviving on Power Bars. They escaped when the climbers pushed one of their captors off a cliff, and then ran 18 miles to the nearest military outpost.

Chris has spoken with his friends by phone, and is relieved that they were OK. "It is a wake-up call," he says, "a reminder about the risks."

After watching Chris Sharma climb on video and at the UCSC quarry, I saw that he is indeed subject to the same gravitational pull as the rest of us. What he does comes from a combination of talent, patience and love for his sport. It is risky, but Chris believes that if he can make even one beginning climber believe in his or her own ability, then those risks take on a significance that surpasses any adrenaline-laced advertising campaign.

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by George Sakkestad

The Flying Trapeze: Sharma seems to float in midair as he moves without effort from one tiny hold to another.

The Flying Trapeze: Sharma seems to float in midair as he moves without effort from one tiny hold to another.

From the September 27-October 4, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.