![[MetroActive CyberScape]](/gifs/cyber468.gif)

[ CyberScape | Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Game Boys

For Santa Cruz's small but growing community of computer game developers, the coin of the realm is big ideas more than big money

By Rob Pratt

THIS ISN'T just a game. At least that's what I think as Michael Bartlow of Santa Cruz game developers Osiris Studios shows me a prototype of one of the company's latest projects. On a computer monitor deep in the warrenlike offices on the second story of a historic Pacific Avenue building, two computer-generated figures shift their body weight side to side. Bartlow, who is the company's audio director, grabs a controller, moves one of the figures around in the desolate game space--background graphics haven't been added yet, so all I can see is just basically a black backdrop--and tells me about the difficulties of making art imitate life.

I get the feeling that the challenge of bringing the computer to a kind of life is what drives Bartlow and the handful of others at Osiris Studios who are creating the next generation of video games. More than churning out mass-marketed diversions, the pursuit of the ultimate game experience is about teaching computers how the world works. In the same way that quantum physics uses advanced mathematics to model the universe, Santa Cruz's small community of game developers uses computer code to break down and describe human gestures and to create in ever-increasing detail entire worlds.

For now, though, the big problem is how to get the upper and lower half of a figure to move independently. Most games like the new one Osiris is working on only handle motion either above the waist or below it--not both simultaneously. With some tricky coding, Bartlow explains, he thinks the programming wizards at Osiris can make it work.

Next door, in the conference room, company president Quinn McLaughlin sets up the big new thing in video gaming, Sega's just-released next-generation console system, Dreamcast. Bartlow and I settle in around the conference table as McLaughlin boots up Soul Calibur, a sword-fighting game set in vivid otherworldly landscapes. Osiris' creative director, Jason Kaehler, comes in and takes a seat at the edge of the room and marvels at the graphics. Judging from his sense of admiration, it's obvious that he has spent many hours playing and analyzing the new gaming console.

"That's all real-time 3D," Kaehler says. The scene as McLaughlin plays swivels around in perspective instead of moving only left to right, dioramalike, as in most console games before Dreamcast. "It used to be that all 3D had to be prerendered and played like a movie clip. Now the hardware can do it real time."

Things are moving quickly with the computer's ability to render real-world scenes, he says. And the end is in sight--the point where computers can render the virtual world as vividly as the real world.

"At a workshop I was at recently, the speaker explained that by the year 2020, computer graphics will reach the color and resolution limits of the human eye," Kaehler adds. "And that's as far as you can go."

In the intent eyes, the baggy clothes and the rush of enthusiastic, idealistic talk from local game developers, I start to think that I have glimpsed a new face of industry in Santa Cruz. Where the high-tech scene on the other side of the Summit by all accounts is a crush of overachievers scrambling to secure venture capital and stock options, the scene in Santa Cruz is more laid-back, more focused on working with a spirited and creative team than earning enough to retire by age 35. In Santa Cruz, the currency is big ideas more than big money, and in the new local economy, a quest to render in precise detail the human imagination is entirely in keeping with the scale of things.

IN THE SPACE of only a couple of decades, the computer gaming industry has bested the dominant entertainment medium of the 20th century, pulling ahead of the film industry in total sales. For 1999, that means several billion dollars were spent on computer games, whether complex PC-based games like the recent runaway hit Half-Life, console games like PlayStation's future fighter franchise Tekken or hand-held diversions like GameBoy's Pokémon.

Compared to the movie industry, though, the computer games industry has just toddled out of its infancy. No longer curiosities akin to quickly produced silent shorts that play at nickelodeons, they are now more like the first full-length films, with ambitious sets and stunts, a devoted fan base for dozens of genres and a level of glamour that has turned gaming characters like Tomb Raider's Lara Croft into virtual stars.

Only in the past couple of years has technology advanced to the point where computer games approach as immersive an experience as a showing of the latest James Bond thriller on the big screen with THX sound.

With this year's debut of Sega's Dreamcast console, which offers dazzling graphics on a level with the high-powered 3D rendering until now only available on PCs, and with Sony claiming that PlayStation 2 (set to hit store shelves in fall 2000) will leapfrog the capabilities of most home PCs, computer gaming is potentially poised at the brink of a megaboom beyond anything the entertainment industry experienced during the 20th century.

"This year it will be more than a $7 billion industry," explains Christian Svensson, chief executive officer and editor-in-chief of MCV: The Market for Home Computing & Videogames, one of the leading trade publications of the computer games industry. ("We think of ourselves as the Variety of computer games," he adds.) "In many ways, it has become a much more acceptable form of entertainment. It's much more pervasive, more people are doing it. Now there are more than 34 million households that play some sort of computer game."

In Santa Cruz County, computer gaming is a nascent industry. Small studios specializing in 3D computer graphics have turned their attentions to developing computer games. Osiris Studios, which is set to move into new Pacific Avenue offices on the second story of the Cooper House, has just inked a deal to work on PlayStation titles with powerhouse console gaming publisher Acclaim Entertainment Inc.

IN THE CRAMPED current offices of Osiris Studios, McLaughlin shows me into the main production area, a space of no more than a couple hundred square feet. Before I left the conference room, McLaughlin had me sign a nondisclosure agreement, and Kaehler and other Osiris staffers looked at me wide-eyed as I walked into the main development and programming room until McLaughlin explained that I'd been "NDA-ed."

The half-dozen people in the room are all fairly young. McLaughlin and Kaehler, just hitting 30, are right at the average age of company staffers. All of the table space ringing the room is cluttered with computer monitors, some flashing the game prototype, and one, Andrew Webster's, showing full-body "skins," or body and facial features for game figures that he's designing. Kaehler tells me that they are working to meet a benchmark where they must demonstrate for a client certain elements of game playability. They've just got everything working, and he hands me a controller to let me see for myself that it actually plays--though sluggishly.

Right now the team is focusing on "physics," or the way objects move around in the virtual game space, and "collisions," the way objects interact with each other. They're both part of one of the most complicated problems of game development: how to make movement seem natural with a given set of hardware capabilities.

For console game developers--groups that work on games designed for stand-alone home gaming devices like Sony's PlayStation or Nintendo's N64--that also means that fledgling startups like Osiris can use the limitations to advantage. While PC game developers must contend with user hardware that continually changes as new PC products become available, console developers know exactly what hardware users will have in their system. Bartlow explains that programming savvy and imagination--more than a handle on this month's gee-whiz hardware gadget--make the difference in console games.

"It's really that last 2 or 3 percent of software performance that can make a game really play well," he says. "To get that, you just have to come up with tricks to do things more efficiently."

Unlike PC games, Bartlow explains, console games don't have the advantage of an operating system like Windows 98 to take care of basic tasks like reading information from a CD-ROM disc. For its recent projects, Osiris has to build the "game engine," or the core part of the software code, as well as outlining game play and designing the graphics.

Osiris, though, didn't start out designing full-fledged games. Like most area start-ups involved in games projects, the company first worked on 3D graphics, beginning as a contractor on larger projects and gaining experience with the development process.

The first game prototype Osiris developed was a speculative project, a mountain-biking game for PlayStation called Fall Creek and named after a now-

I WALK INTO the offices of 3D graphics group Virtual Alchemy Studios and find creative director Rennie Saunders flat on his back, eyes shut, listening to an ambient CD of music by Dead Can Dance chanteuse Lisa Gerrard. He gets up quickly as I apologize for interrupting his nap.

"Doing this for the past year and a half, I've gotten pretty good at taking micro naps," he says.

Outside his office on the second floor of a Soquel office building, programmers and designers are moving around furniture and computers and wiring up equipment. A Pac Bell technician is frustratedly trying to find the culprit who tied up the main voice line with an Internet connection so that he can finish setting up a high-speed data line.

"We really came together around building a game," Saunders says. "But none of us had any experience in doing one, so we thought, 'Let's do a lot of these other things to get ready.' It's building up our skill base."

Much of the work Virtual Alchemy has done is to produce 3D computer animations that large companies use as part of presentations or demonstrations at trade shows. But even though the company's game project doesn't have a formal timeline right now, staffers get together regularly to fine-tune their vision.

"The next thing we're going to do is design levels for Half-Life," he says. (One of the features of the bestselling PC game is a "level editor" that allows skilled game players to design their own game components.) "Sometime you get people playing games with the door closed, and when you pound on the door, they yell out, 'I'm doing research.' "

The company's big recent project was to put together a bunch of simple 2D games for children 5 to 11. The finished product has earned a lot of enthusiasm from their client, Lasertron (which makes arcade skill games), and from amusement park and resort customers. Next up, says chief executive officer Karen Stewart, is a project involving the company's game engine and real-time 3D graphics rendering.

CHRISTIAN SVENSSON of MCV magazine explains that the turning point for the computer games industry came with Sony's introduction five years ago of the PlayStation. The electronics and media giant had been working on building a CD-ROM drive for the next generation Nintendo console. When the deal fell through, Sony decided to build and market its own console. It looked like a flop waiting to happen--Sony Imagesoft, a computer games subsidiary, had "produced zero hits," Svensson says. But PlayStation had a "brilliant" marketing campaign that "made Sony sexy and chic."

Basically, Svensson continues, Sony made it easy for third-party developers to write and publish games for the PlayStation platform.

"Sony did a great job of evangelizing their system, and they ended up with a whole lot of games," he says. "At the outset, that was the right policy: to be friendly to publishers. Also, using CD-ROMs [as opposed to RAM cartridges that had been standard on console games until then] was technically risky but ended up costing a lot less. If you're doing a game of 100,000 units with a RAM cartridge, the cost for each is $8 plus $7-$9 in licensing, and that's about $1.7 million in the hole right from the start. A CD-ROM--including packaging--is about $1.75 a unit."

Like the film industry, Svensson says, the games industry has quickly become the province of large publishers with enough money to finance development and to underwrite marketing and distribution. Most of the time, small game-development studios get their start just as Osiris did: doing contract work to build up a skill base, eventually getting the nod from a large publisher to go ahead with a full-scale project.

"The licensing and engineering costs run into the millions of dollars," Svensson says. "It's really difficult for the guy in the garage to create the next big hit. Every once in a while, though, there is a Blair Witch Project that comes along. But it's becoming very difficult to compete from a garage standpoint."

Perhaps the biggest difficulty, explains Osiris' Kaehler, is coming up with the buy-in capital. Even before taking its first job, Osiris had to find investors who could lay out money to buy the hardware and software needed to start programming and developing graphics. For console game developers, the major costs don't end there.

"You have a steeper barrier to entry because the hardware manufacturers control the show," he says. "You have to go before the emperor of Sony, and that's where soft science comes into play. You have to show them your company profile, where the company is in relation to the console's product cycle. Then you have to buy the programming environment, and that's about 20 thousand."

'GAMES HAVE SUCH a tough skill-set area," says Gaben Chancellor of Dramatis, a 3D computer graphics studio that over the summer designed a game demo for Creative Labs based on the Unreal PC game. "You have to have a strong technical base, and you have to be artistic and creative. There are a lot of people out there who have plenty of technical skills but not the creative side, so you end up with a lot of 'me too' games that just repeat what was popular last year. That's why we don't have a lot of games that are creative."

The Santa Cruz area, with a close proximity to Silicon Valley and a strong arts community, certainly has potential for developing a strong pool of games developers, Chancellor continues. But the games industry as a whole doesn't have a locus the way the movie industry centers on Hollywood. Ultimately, say Santa Cruz game developers and computer graphics professionals, the booming new entertainment industry works like anything else in the Internet economy--it comes down to who you know.

"The fact is that the availability of bandwidth and interconnectivity make it so that Silicon Valley isn't really the hub of gaming," Chancellor says. "Neither is Los Angeles or San Francisco. Places like Austin have strong game developer scenes--San Diego, too.

"It's all about contacts in this business," he continues. "Just because you're in Silicon Valley doesn't give you a leg up on who's doing what where and when."

Still, it's an industry that's open to outsiders. With a culture founded by tinkerers working in garages and ramping up their big ideas into multinational corporations, the high-tech industry remains enticing to people with skill and savvy.

"I have a brother-in-law up north who just designed a traditional board game," says Steven Beedle, president of the Santa Cruz Technology Alliance. "He's having all kinds of trouble getting noticed, and what he's discovering is that he would have been better off making a computer game first. It seems that computers are so hot now that it's open to everybody. I think it's definitely more welcoming to outsiders than older industries."

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

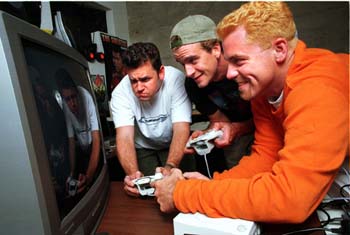

Serious Game: Wizards of Santa Cruz's Osiris Studios (from left) Jason Kaehler, August Johnson and Quinn McLaughlin use computer code to create computer worlds.

defunct trail near Felton. Osiris so far hasn't been able to interest any publishers in the game. But, McLaughlin says, it demonstrated that the company in its two and a half years of existence has developed the skill base to take on game development projects, and it has helped the company to hone its focus on projects related to extreme sports.

From the December 1-8, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.