![[Metroactive Books]](/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

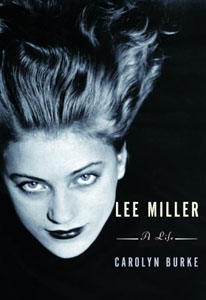

Thoroughly Modern Miller

Local resident Carolyn Burke's new biography, 'Lee Miller: A Life' is a multifaceted gem

By Sarah Phelan

In 1997, Santa Cruz resident Carolyn Burke saw Becoming Modern: The Life of Mina Loy--

her intricately researched biography of the once internationally notorious writer of shocking free verse, who faded to obscurity in her later years--received to critical acclaim. Nine years later, Burke is seeing her latest impeccably researched and written biography, Lee Miller: A Life, just published by Knopf, get rave reviews in Vogue, W, Publishers Weekly, the New York Sun, More and Style.com, to name just a few.

In a recent interview at Caffe Pergolesi, Burke connected her knowledge of Mina Loy with that of Lee Miller, an American blonde bombshell who took Paris by storm in her youth and went from Vogue model to war photographer, Surrealist muse to Condé Nast reporter, sexual adventurer to mother, only to fade into the role of gourmet cook in her later years. To add insult to injury, her retreat into the realm of the kitchen took place as her second husband, Sir Roland Penrose, an English artist whose career came to eclipse Lee's during their lifetimes, continued to philander with women who by now were half his age.

METRO SANTA CRUZ: There seem to be many similarities between Mina Loy and Lee Miller. Beautiful, brilliant, ultramodern and ahead of their time, then fading into obscurity as they age. Do you think that was the fate of brilliant women?

Carolyn Burke: The lives of Mina Loy and Lee Miller present complementary aspects of what intelligent, artistic, liberated women could do at the time. Agewise, they could have been mother and daughter. Mina's dates are 1882 to 1966, while Lee lived from 1907 to 1977. Lee was the daughter Mina didn't have, in the sense that Mina was critical of her own daughter, whom she found too conventional. Mina admired Lee and her free spirit. In writing about both of them, I feel I've completed complementary portraits of modern women. Mina was introspective, while

Lee was so out there. She met life head on.

I came away from the Lee Miller book with a profound distaste for Roland Penrose, in large part thanks to his relentless philandering and the pain it caused Miller as she aged. Is that a fair reaction to Penrose?

Women are more likely to react to Penrose like that than men. I tried to be objective about him in spite of myself. That's the problem in biography. There are people you like, and people you like less.

Which part of the book did you enjoy writing the most?

The war years. I loved writing that part, though it was incredibly difficult, because I had to keep on consulting histories of battles and so on. Another part I liked was Lee's later years. Legend had her as "unhappy, drunk and embittered," but I learned from her friends that she was quite amused by her new passion, cooking. I was glad to counter that idea of her as an aging alcoholic.

You write that Roland claimed that Miller lost interest in sex after their son Antony Penrose was born.

Yes. I was told by her family and friends that she lost interest after his birth but that she continued to flirt with younger men. Something strange happened to Miller during this period. Maybe it was a loss of libido. She'd had such an active sexual life earlier, perhaps she didn't want to be bothered.. It might also have been a form of post-traumatic stress disorder, after Lee accompanied the American troops from Normandy to Dachau as Vogue's war correspondent, an experience that forever haunted her. Lee's experiences at the concentration camps were devastating. I don't think we can underestimate what that did to her as a woman, as a sexual being. She never got the stench of Dachau out of her nostrils. She was a burned-out case towards the end of the war, and just when she might have re-established her emotional life with Penrose, she got pregnant. She was trying to recover from the war without help and without any understanding from those around her.

You document how Miller was raped when she was 7, contracted gonorrhea as a result and subsequently described herself as 'damaged goods.' Is it possible that her 'free' sexual behavior was actually a case of low self-esteem?

I think a lot of contemporary readers would see it that way, but I'm not so sure. I think Lee disassociated her sexual life from her emotional life. I think she came to see sexual freedom as a way to live on an equal footing with men, and to demonstrate to herself her own power. As a young woman, she was so dropdead gorgeous. Sex was one way to affirm herself within that milieu. Her life is a very modern story. It's not so different from what's still happening today. Societal expectations of women in their 40s, particularly then, didn't leave much room for a powerful sexual being who also happens to be a mother and an artist. After the war, there was a massive return to a more constricting idea of femininity. Women no longer dressed in overalls and uniform or worked with machines at men's jobs, a situation that Miller had photographed for Vogue. It was back to aprons and babies--a huge turnabout that Miller couldn't really accept.

Did you feel any sadness about Lee's latter years?

In my own heart, I wish she hadn't married or settled in England. But thank goodness for her friends and her own wicked imagination, her "defiant cooking" as a younger friend of Lee's called it. She did what she could in those limited circumstances. She kept her sense of humor.

I remember feeling delight when I read that she laughed when Roland was knighted.

And she enjoyed answering the phone as "Lady Penrose" in her American accent. She really did enjoy cooking. She had an obsessive temperament in that she poured herself into gourmet cooking, even though there wasn't much to cook with after the war. She was very down-to-earth and hands-on about it.

You met Lee Miller in 1977, while researching Mina Loy. Was it this meeting that made you want to write about Miller, or was it as a result of working on Loy?

I became interested in Mina Loy while living in Paris, as she was mentioned in all the expatriate memoirs, but there was almost no information on her. When I moved to Santa Cruz, I started to research Loy and found her poems, which could have been written in the 1970s. In the case of Lee Miller, I was drawn to her because when I was researching Mina's life, we happened to meet. One woman led me to the other, but it was the visceral shock of first seeing Lee's concentration camp photos that made me feel I had to write about her. That happened in 1990, when I saw Lee's photos in the first traveling exhibition of her work organized by her son. Her war photos were a major part of that show and I was knocked out by them. But I didn't start work on the book until 1997, after her son Antony Penrose encouraged me to work in her archives,having read my Mina Loy book by then. It took about five years from beginning to end to write Lee Miller, then two more years before it could come out because of issues with the estate.

Reading your biography, I felt that the sexual freedom inherent in the Surrealism movement worked for both men and women when they were young, but only men in their latter years. Is that a fair interpretation?

Surrealism was fairly kinky and voyeuristic, but at the same time, women like Miller, being no fools, saw that there was room within that movement to live more creatively--provided that they could work out ways to collaborate with the men, who saw them primarily as muses. But in some portraits that Man Ray took of Miller when she was in her early 20s, when she was his assistant and lover, she looks really cross, as if she's tired of posing as his fantasy woman. For the most part, Lee went along with it. She was very young then and the Surrealists were the most inspiring and unconventional group of people you could consort with, if you were a consort. They also opened up doors to her. Through Man Ray, Lee met Jean Cocteau, who chose her as the leading lady for his film Blood of a Poet. Lee went along with Man Ray's vision of her as a femme surrealiste, but in the end she broke away and returned to New York to set up her own studio. She was very quick and clever at picking up whatever was valuable for her in what came her way. And she had no hesitation about using her good looks, as one more card she had to play.

Did she talk to you about how she felt about being perceived by men as the 'cook' in her latter years, while her husband carried on with women half

her age?

When I met Lee, she knew she was dying and she was very detached, even from the most difficult things in her life. I think she'd mostly come to terms with Roland's amours, except for the French trapeze artist named Diane Deriaz. She was the one who recalled with satisfaction that Cocteau failed to recognize Lee when she was in her 40s. Lee's friends told me she couldn't abide Diane, though she didn't talk about her to me. When I met her, she was very keen on babies for the first time in her life, in her role as grandmother. It was amazing that she opened up to me, after I happened to sit beside her at a public event in Paris and recognized her profile. After that, we had several "dates." She was a very open, frank, no-nonsense kind of person, if she liked you. She was, as her friend Dave Scherman said, a mensch.

Was Surrealism the inspiration for the social upheavals and artistic and sexual revolution of the 1960s?

The slogans of the May '68 uprisings in France came right out of Surrealism, and that era and those circles. The desires expressed in 1968 in intellectual and artistic circles owe a lot to Surrealism--as does that period's political naiveté. Some called Lee Miller and Roland Penrose "champagne socialists." As such, they were similar to the radical chic circles of the 1960s and 1970s in the U.S. But it's good to have progressives backing left-wing movements. For example, Roland contributed his paintings to anti-Franco art exhibitions and Picasso joined the Communist Party after World War II, but their political sense was not always as acute as others might have wished. The Communist Party used Picasso as its star. Lee Miller had sharp political sense. She was a good social analyst. But I don't know how much the youth culture of the swinging 1960s in Britain actually looked to the Surrealists. They might have seen them as old geezers! But in the artistic world, Dada and Surrealism are still seen as sources of inspiration to younger generations.

Do you think you would have lived like Lee Miller, if you'd been born at the beginning of the 20th century?

I don't know if I'd have had the guts, the determination or the imagination. I didn't have the backing of powerful men. As a 19-year-old student living

in Paris, I was drawn to an older artist, but I was living in a maid's room, teaching English for a living, and didn't have anyone's financial support. I

was always aware of having to make my own way. Both Mina and Lee knew how to get support from the men in their lives, whereas I was such an independent-minded feminist in

those days.

[ Santa Cruz | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

Kindred Spirits: Author Burke, whose previous biography portrayed Mina Loy, likens Miller to the daughter Loy didn't have.

Carolyn Burke will read from 'Lee Miller: A Life' on Wednesday, Dec. 14

at 7:30pm at the Capitola Book Café,

1475 41st Ave., Capitola. (831.462.4415)

From the November 7-14, 2005 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.