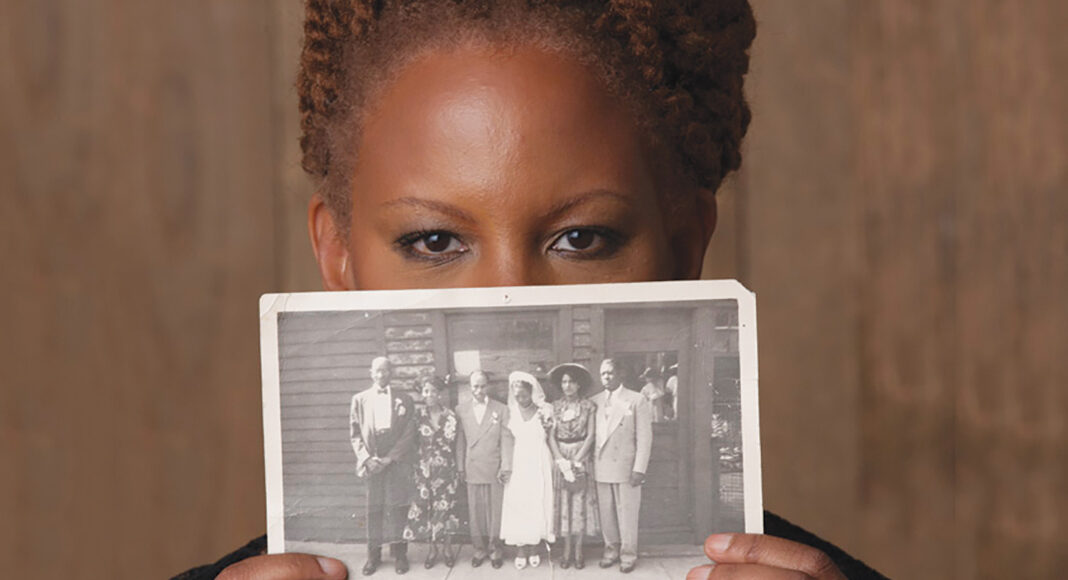

On Regina Carter’s family tree, there is a blank spot where her maternal grandfather should be. Growing up, no one talked about him and when she asked, family members wouldn’t tell her anything.

“A lot of my aunts and uncles will just say they didn’t remember him,” she says. “How do you not remember your father? I knew there was something there. There’s a reason people are not remembering and I have to get to the bottom.”

Carter finally found a relative who would share stories about her grandfather with her and answer her questions. When asked if she found what she was looking for from the stories, she simply says, “I did.”

Filling in the details of her family story led Carter to a familiar place: music. A born musician who was playing the piano by the age of 3 and took up the violin at 4, Carter is now a world-renowned jazz violinist in the lineage of greats, including Stéphane Grappelli, Billy Bang and Stuff Smith.

Carter turned to folk songs from the late-1800s in an attempt to connect with her grandfather. In particular, field recordings from the Alan Lomax collection and music from the Alabama Folklife Association provided a glimpse into what her grandfather’s life might have been like. It also inspired a musical project that would become her ninth solo album, Southern Comfort.

The album is a haunting reworking of old folk and gospel tunes, spirituals, ballads, children’s songs, and blues, brought to life with Carter’s soulful and lovely playing. The album showcases familiar tunes, including “Trampin,” “See See Rider,” and “Honky Tonkin’,” as well as lesser-known ones such as “Blues de Basile” and “Cornbread Crumbled in Gravy.”

Where many of the field recordings are single voices, or a group of voices, Carter and her band draw out unexpected elements of the tunes, with crashing drums, accordion, electric guitar and, of course, Carter’s violin leading the way. The result is an emotional and personal exploration of the past, through the lens of modern styles and tools. When Carter plays the songs live, she plays snippets of the original raw and scratchy field recordings to give the audience context.

“Listening to the songs was a way of transporting me,” she says. “It’s my way to make a connection to who [my grandfather] might have been with a little bit of information that I had—to try to understand what life might have been like.”

Born and raised in Detroit, Carter traveled to the South with her family in the summertimes to visit relatives. Those visits provided stark contrast for a city girl. There were no sidewalks, no TV, and everyone used outhouses. The trips were also an opportunity to connect with the folk music of her family and extended community. Carter has vivid memories of singalongs with her family and friends. As she recalls, someone would start playing the piano or pull out a guitar, and whoever was around would join in singing.

“I call it folk music,” she says. “Nothing I would even remember today. I just remember it as a gathering—just what was happening.” She adds with a laugh, “We didn’t have TV, we really had to just deal with each other.”

Since Southern Comfort, Carter has been touring and performing the songs for audiences around the world. Her next project, which is still in the very early stages, is a tribute to Ella Fitzgerald. Carter wants to find and bring to light tunes that are less well-known than the standards the great jazz vocalist recorded.

For Carter, who does volunteer hospice work and regularly plays for people in nursing homes and hospitals, music is a gift that enables us to connect with one another in a very intimate way. The project is another way to connect with music as a means to transport ourselves and honor those who have gone before, she says.

“It puts everything in perspective,” she says. “We always say, ‘Oh, music is so powerful and so moving.’ It sounds like a cliche, but it is. It’s real. When you have those moments, you know it.”

7 p.m. & 9 p.m., Monday, Feb. 29. Kuumbwa Jazz, 320-2 Cedar St., Santa Cruz. 427-2227. $30-$35.