Love and peace. Sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. What else did we need? The Age of Aquarius was busy gearing up for its patchouli-scented 15 minutes, and California was the place to be. Ground zero of that back-to-the-garden odyssey was the San Francisco Bay Area, with Santa Cruz and its surrounding mountains serving as the ultra-hip backyard.

Everyone who could roll a joint, hitchhike, and/or fake a laid-back attitude headed West in advance of the 1967 Summer of Love. Many arrived early, already attuned to the spectacular setting, weather and vibes of our seaside paradise. Along with other communes dotting the West, such as Taos and El Rito in New Mexico, the Hog Farm in Sonoma, and Ken Kesey’s digs in La Honda, Santa Cruz had already established itself as a home base of alternative lifestyles, with plenty of shady canyons and inaccessible mountain acres for those who needed to chill out (or flee the Establishment for one reason or another).

Three new books offer first-hand perspectives and authentic analysis to the chorus of hippie-era memoirs, as the summer of 2017 approaches, marking a half-century since the brief flowering of utopian ideal. Each, in its own way, serves as a scrapbook of the time.

It’s worth noting that the half-mythic, half-prankster persona of Neal Cassady (immortalized by Jack Kerouac as Dean Moriarty) passes through each of these books. Cassady was the first sales clerk at the Hip Pocket Bookstore and a fixture at Ben Lomond’s Holiday Cabins as well as Kesey’s La Honda spread. Complex, drug-drenched, handsome, he was a one-man bridge from the Beat to the Hip era. Indefinable, yet omnipresent.

“Trying to capture Neal with words is like trying to find the baby Jesus in a Snow Globe,” former Merry Prankster Lee Quarnstrom told me recently. Clown prince and activist Wavy Gravy, a man for whom the hippie era never ended, also pranks his way through these memoirs, spreading joy and revolution wherever it was needed.

‘Hip Santa Cruz’

By the time the Hip Pocket Bookstore opened on Pacific Avenue in 1966, the tie-dye was cast.

“That was the beginning,” says mathematician and hip-era chronicler Ralph Abraham. “The minute the Hip Pocket opened, that marked the real beginning of the Santa Cruz phase of hip culture.”

“People came and sat on the floor, reading books, never buying any,” Abraham recalls of the Hip Pocket. “Which is why it soon went broke.”

A hotbed of hip culture, Santa Cruz attracted the royalty of the drugs and music scene. “In the spring of 1966, a benefit concert was held at the civic auditorium in Santa Cruz. [Felton dentist] Dick Smith and his wife were among the organizers, and he also provided the light show,” recalls eye-witness Doug Hanson.* “The first act was Big Brother and the Holding Company, sans Janis [Joplin]—she was back in Texas on one of her first failed attempts to dry out. The headliner was Jefferson Airplane. Dick Smith, who embedded gems in the dental work of Ken Kesey and Wavy Gravy, also set up prototype light shows at The Barn in Scotts Valley, another venue attracting local hippies, acid-heads, and road bands traveling between L.A. and San Francisco.

“I knew that moment was miraculous at the time. Absolutely,” says Abraham, whose cavernous California Street Victorian mansion was both a communal household and crash pad for dozens of hard-core searchers. “People my age were more aware, because we were older and had a history both before and after that moment. The younger people were too stoned to realize it in the same way.”

In retrospect, Abraham believes, “it ended because it was unsustainable. A lot of people had enormous amounts of pain. The drugs covered it up, but then once the moment was over, the pain returned.”

Abraham, who had left a tenured teaching job at Princeton to settle in Santa Cruz, brought with him a wife and children—“which was very unusual for a communal house.” Hip Santa Cruz (2016) offers rare first-person accounts of Santa Cruz during the 1960s, including Abraham’s own ambitious trips through spiritualism, psychedelics, blackjack, teaching in London, and being homeless in India and Amsterdam after his wife joined a southern California cult. Eventually he returned to teaching at UCSC, pioneering theoretical research in fractals and chaos theory before his retirement.

“It ended because it was unsustainable. A lot of people had enormous amounts of pain. The drugs covered it up, but then once the moment was over, the pain returned.” — RALPH ABRAHAM

“Drugs defined the culture. The arrival of cocaine and heroin marked the end of the hip era, though lots of that era’s cultural changes still survive—psychedelics as therapeutic, gay liberation, feminism, organic farming, and yoga,” says Abraham.

The golden moment of the mid-1960s, says Abraham, was like an island with its own ecology, myths, folk music, styles of dress, ethics, and food preferences. “Once the eruptions of the 1960s subsided, we were a cultural island peopled by those who remembered psychedelics as a supremely positive life-transforming time.”

The metaphorical mainland, many thousands of miles away, “was peopled by those who missed all that, or had rejected and regretted those times,” he says. Calling himself a “vegetarian, animal-loving, recycling, rock-’n’-roll-dancing hippie,” Abraham says he’s “still seeking the company of his fellow islanders, and practicing compassion for those stranded on the mainland.”

‘Inside a Hippie Commune’

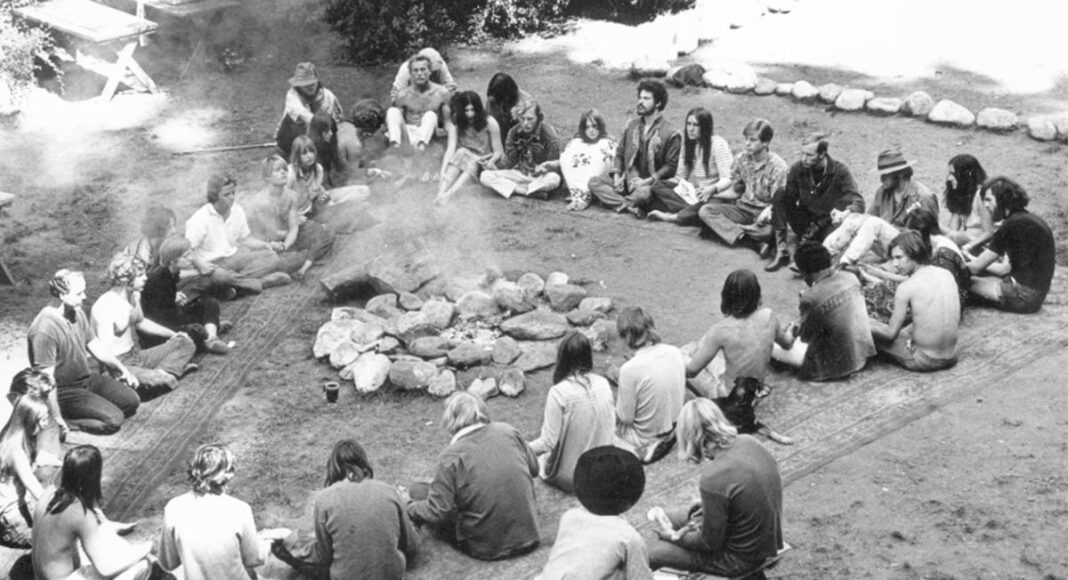

Gathering the vibrant memories of her almost fairytale youth into a photographic scrapbook of the hippie flowering, Holly Harman opens a window on the simpler, back-to-the-land era of Ben Lomond’s Holiday Cabins commune, circa 1966-1968. Filled with personal photographs taken in the San Lorenzo Valley, Inside a Hippie Commune documents the gathering of those on mellow vision quests determined to live together, grow their own food, and let each afternoon unfold in a haze of sweet weed.

Harman’s mother had started the nearby Bridge Foundation art school, so Holly had access to the communal cottages while she was still in high school. “We had the art school, then we moved to a ranch house near the commune. I started hanging out in 1966 first at Boxer Apartments then moved to Holidays,” Harman says.

The Holiday Cabins occupied a secluded property bordering the San Lorenzo River. The pastoral, ramshackle collection of dwellings in Ben Lomond had been “sitting empty” for some time before it became a place to hang out or simply pass through on the part of luminaries like the Grateful Dead, Timothy Leary, the Jefferson Airplane, and Ken Kesey’s Pranksters. The site flourished for a year and a half but began to unravel once a salacious Los Angeles Oracle article drew public attention—and wannabe hippies—to the commune from all over the country. And the Summer of Love brought more, not all of whom were as interested in “love and peace” as the original mountain dwellers.

“Everyone fixed their cabins, working on the foundations and walls, growing gardens, keeping it nice,” Harman recalls of Holidays’ zenith. “The day’s work was planned together around a morning campfire. Everybody gathered, held hands and chanted “Om” before deciding how the day would unfold. The commune-dwellers worked on renovating their cabins after breakfast, which, she recalls, was usually whole grains and fruit. “Then it was crafts, gardening, playing music, smoking weed, kicking back,” Harman says. Holidaze, indeed.

The peaceful, innocent vibe of the place comes through in the hundreds of vintage photographs of Harman’s book. Lots of tie-dyed T-shirts, leather vests and long skirts. Glimpsed from the 21st century, it all looks rather tame; the hair was not as long as many had boasted.

“Village life in the mountains of northern New Mexico offered a chance to see how it felt to make it on their own in a physical and human landscape that seemed to come straight out of peyote dreams and illuminated Hollywood Western movie stills.” — BENJAMIN KLEIN

“There was a lot of spirituality up and down Alba Road, and a hip scene in this vortex—Ben Lomond, La Honda and Santa Cruz,” Harman maintains. “But after a year, things began to change. The people who came in then were all about drugs,” Harman says regretfully. “I think they came because the cabins were so accessible, so close to the highway.”

The original hippies, the ones who had gardened and renovated and been content with brown rice and granola, began to leave. The large-scale glossy pages of Harman’s book are filled with newspaper clippings, oral histories, and personal photographs of now far-flung participants.

“Some left for careers, some wanted to go back to school, some to build families. I look back and think how it was a great year—every day was a new experience, a new adventure. So exceptional, like living inside a story,” she says. Harman moved on to study at California Art Institute in 1968 when she was 17. Since then she has lived in the Bay Area, working in advertising and graphic design.

‘Irwin Klein and the New Settlers’

New Mexico and its rugged terrain has long beckoned renegade artists and escapees from the bleakness of cities, establishment jobs, and bourgeois codes. Providing haunting imagery and anthropological context, Benjamin Klein’s newly published book Irwin Klein and the New Settlers, offers gritty insight into a harsher landscape of bohemian lifestyle. Lacking the sunny seaside temperament of Santa Cruz, the El Rito settlement was challenged by New Mexico’s high elevations and hard winters. The volume of black-and-white photographs taken by Irwin Klein between 1967 and 1971, records the efforts of counter-culture settlers to El Rito, New Mexico—“dropouts, utopians, and renegades,” (in the photographer’s words), who did their own thing for as long as they could, before mostly moving on and growing up. El Rito already had a cluster of communal dwellings before the diaspora of the 1960s, when Irwin Klein joined his brother Alan and those Irwin called “the children of the urban middle class.” Through El Rito came Beat poets, and archetypal gurus of psychedelia such as Wavy Gravy and the Diggers. Klein’s stark images are gorgeously mounted in this University of Nebraska Press volume and accompanied by essays from his nephew, historian and UCSC alumnus Benjamin Klein, who helped guarantee that the important visual legacy his uncle never lived to see exhibited will ensure his place in American documentary art.

“Village life in the mountains of northern New Mexico offered a chance to see how it felt to make it on their own in a physical and human landscape that seemed to come straight out of peyote dreams and illuminated Hollywood Western movie stills,” writes editor Klein and collaborator David Farber. Indeed, the images are filled as much with Wild West bravura as they are with hardship, loneliness, and communal struggle.

The volume’s spearhead and editor, Benjamin Klein, came to Santa Cruz after growing up in various communal settings, including The Canyon in the Oakland Hills. “The book’s challenge was reconstructing my uncle’s movements,” Klein says. Wanting to become a photographer, he had dropped out of grad school. But the big picture magazines, Look and Life were on the wane.

“Earning a living as a photographer just wasn’t viable,” he says. After a stint at San Francisco’s Zen Center, he stopped at El Rito on his way back to the East Coast.

“It’s right next to Carson National Park,” Klein points out. “Winters are hard. It’s remote. It’s impoverished. And it was violent. Shoot-outs were common.” It was not the love-peace world of John Lennon.

“Irwin was older than most of the settlers, he wasn’t 18. He came through, hung out, visited, and then moved on,” says Klein.

Achingly captured are a spare yet joyful wedding, lines waiting for daily meals, the backbreaking labor of making adobe bricks, shepherding flocks of goats, and the unfocused body language of marijuana-laced torpor. Dorothea Lange and Brassaï haunt these compelling images of a powerful, yet fleeting, moment of baby-boomer youth.

Embraced by incisive essays, Irwin Klein and the New Settlers displays the counterculture in New Mexico as yearningly distinct from—yet subliminally joined to—the hippie flowering in Santa Cruz. Together this trio of new books offer many paths back to an indelible time.

_________________

HIPPIE BOOKS

*Doug Hansen, memoir. ralph-abraham.org/1960s/

Lee Quarnstrom. When I was a Dynamiter! Amazon.

Ralph Abraham. Hip Santa Cruz: First Person Accounts of the Hip Culture of Santa Cruz, Bookshop Santa Cruz, Logos Bookstore, Amazon.

Benjamin, Klein. Irwin Klein and the New Settlers: Photographs of Counterculture in New Mexico, Amazon.

Merimée Moffitt. Free Love, Free Fall: Scenes from the West Coast Sixties, Amazon.

Holly Harman. Inside a Hippie Commune, Second Edition. harmanpublishing.com; Amazon.

Good read. I was there, all of 15 yo to start. Happy to see a photo of my older brother in Harman’s book at Holiday Cabins I hadn’t see in long time.

I currently own Holiday cabin property. Charmaine Kincaid was my aunt. Would love to get more pictures of the property from those times and earlier