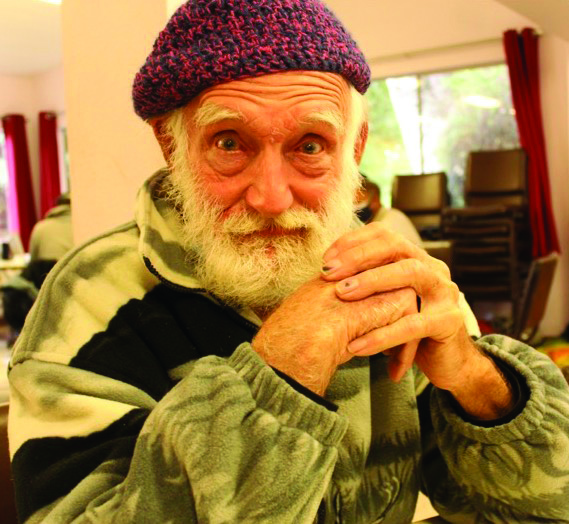

South Africa was not yet an international surf destination during Nicholas Whitehead’s childhood. Nevertheless, Whitehead, now 82, had an exciting life taking yearly trips to the ocean, working for the South Africa Broadcasting Corporation as a journalist in his home country, and for the BBC in London typing up international news. He also worked as a film editor, and eventually followed his parents to New York.

While employed as a correspondence clerk at Popular Science Magazine in the 1960s, he became fascinated by the emerging countercultural scene.

“I dropped out and joined the hippie community in Santa Cruz County, in Ben Lomond,” he said. “I decided I was going to take a chance and see what this hippie lifestyle was all about.”

Whitehead remembers girlfriends crying on trips to Fort Ord to take their boyfriends off for war in Vietnam, the time the Hell’s Angels showed up to smoke marijuana and tried to have sex with their girls, and the animosity of more conservative neighbors, who helped hasten the end of that era in local history. Hippies were some of the first people he saw in the United States who were homeless, he recalls, pointing out in that case, they chose the lifestyle. Decades later, Whitehead would find himself without a roof over his head. That’s different, he says.

He’d worked for years restoring apple orchards and tending gardens. But then, his long-time companion—who’d been experiencing congenital health problems—died.

“Her life-energy ran out,” he said. “I could no longer afford to pay the rent.”

For about a year he was able to stay with friends, sometimes in a room, other times on a couch.

“But you can’t do that forever,” he said. “Losing your partner and your place, that can disorient you. I slept in my car for probably a month during the rainy season.”

Luckily, he knew about a special program organized by people of faith in the area to assist homeless residents. That’s because he helped get it going in the first place. He remembers working with the late Annette Marcum, of Valley Churches United, on encouraging local churches to allow people experiencing homelessness to stay overnight.

“I went to three churches myself and persuaded two out of the three to do that,” he said.

Sam Altis, is the program manager for its modern incarnation—Faith Community Shelter. Now, the organization counts Christian, Jewish and Buddhist communities as members. Generally, they take turns allowing a group of around 20 people experiencing homelessness to sleep in their facilities, although that number has been slightly reduced during Covid-19. Crafting a healthy space starts with ensuring there’s a safe environment on-site, according to Altis.

“We try to be really clear about what our boundaries are,” he said, giving the example of their strict no-drugs, no-weapons policy. “They can develop a plan to move towards housing.”

While about a dozen churches, synagogues and temples have opened their doors, there are 40 faith communities that pitch in with home-cooked meals. Taking care of 16-20 people is just a drop in the bucket when it comes to the 2,167 people discovered to be homeless across the county during the 2019 Homeless Point-in-Time Count. The research found Scotts Valley had 0.35% of the county’s total “unsheltered” population, down from 1.45% in 2017, although service providers caution this figure doesn’t tell the whole story.

“There are definitely folks experiencing homelessness in Scotts Valley—it may not be as visible as if you were to go down to the Benchlands,” Altis said, adding “unhoused” can include people who get evicted from their apartment and can’t find a new one, or couch surfers. “They aren’t as visible. They aren’t in a tent outside. They’re just trying to get by and take whatever steps they can to get into permanent housing.”

The day the Press Banner visited the shelter program, Feb. 24, it was being held at St. Philip the Apostle Episcopal Church, in Scotts Valley. That night it was also running its “Pip’s Pantry” food bank program, which serves about 15 to 20 families per week.

“Most weeks we see somebody new, and in 2022, we are seeing more people,” said Rev. Katherine Doar, the priest in charge.

The building used to be a motel, so it works out nicely for hosting unhoused people, Doar says. They decided to let the guests stay for a whole month, she added, since the pandemic has meant those rooms are vacant anyway.

“We have the space, and there are people who need places to sleep,” she said. “This is near and dear to the heart of the people of St. Philip—and how we see our ministry in the world—and is something we weren’t able to do during Covid.”

There are more people in need in the affluent community than people might think, Doar adds.

“There’s a lot of severe poverty in Scotts Valley,” she said. “We’re always asking, ‘How is God calling us to serve in this place?’”

Al Anthony, 68, who’s originally from Ontario, Oregon, sat at a table in the center of the dining room. He said he moved to Portland to avoid falling into the churn of the criminal justice system that had consumed so many of his hometown friends. Anthony thought he could easily land a place to stay once he arrived.

“But that didn’t work out,” he said. “So, I just said, OK, I’m just gonna live on the streets.’”

When he moved to Santa Cruz County with some friends he continued without a home.

As he got older, Anthony did tire of the harsh realities involved with being homeless, but still avoided shelters, because he heard they were full of people starting fights.

“I just decided I’ll stay where I’m at—until I got into this shelter,” he said. “I started out in this shelter as just a resident. For the last eight-and-a-half years, I’ve been the night monitor.”

He’s hoping to get an apartment to go to during the day, while still contributing to the interfaith program at night. The day after the interview, shelter members celebrated his 69th birthday with cards, presents and cake—to appeal to his sweet tooth.

Altis says the opportunity for the shelter to remain in a single place for an entire month has been helpful in providing constancy to program participants, which makes a big difference with things like getting ID cards.

“If you’ve ever had to track down your birth certificate or some other document, it is an inconvenience,” he said. “But if we have the stability of a place to live, you can handle it.”

Caroline Mann is the executive director of Wings Homeless Advocacy, a Scotts Valley Christian organization that has helped some of the shelter users apply for documents.

“Everybody needs to have a birth certificate to get a housing voucher,” she said, adding it has five notaries who volunteer their time. “We got 500 birth certificates for people last year.”

The official homeless count found 16% of respondents said they couldn’t get government assistance because they had no fixed address, while 12% said they had no ID, and 10% said they’d never applied. Once people experiencing homelessness do manage to secure funding and a receptive landlord, Wings furnishes the new home, provides cleaning products and kitchen supplies, and stocks the bathroom with toilet paper.

Many of the recent apartments they’ve housed people in have been located in the San Lorenzo Valley and South Santa Cruz County areas, she said.

“You’re probably not going to stay housed if you don’t have what you need to be successful in that space,” Mann said, describing the steps they go through to make sure people have what they need to start their new life. “We believe there’s dignity with that, as well.”