These last years have been so fucked up in so many ways, we’re all tired of talking about it. We’d love to look for a ray of hope, but that would require a lunatic break with reality—we all sense it’s going to get worse before it gets better.

So we pull away and ignore the horror show, or we blow our circuits going all in on sordid detail: “Wait, what? The bone-saw guy, that Saudi prince who ordered the murder of a heroic journalist, now screwed us all by making a deal on oil prices with Putin to help the disgraced Russian leader commit more war crimes in Ukraine?” When can we jump off this hamster wheel of endless outrage and revulsion?

Or, to put it another way, fear and loathing.

I don’t have a way out, but I think it’s time we start looking together for some new answers. What kind of kick in the ass would it take, for example, to prod more contemporary writers to stop mailing it in and going belly-up passive in this time of dire crisis, and channel some of the fearless intensity and readability of writers forged in the fire of 1960s California like Hunter S. Thompson and Joan Didion? Then as now, too many in the national press were cautious, callow and cowed, but the new writing out of California had an energy that snapped people awake. It was flat-out fun to follow these writers’ sometimes highly quirky but often deceptively thoughtful takes on the issues of the day.

The example of Thompson at his best looms large now given that his greatest subject was the depravity of Republican President Richard Nixon, who resigned in shame in August 1974 (on my twelfth birthday) and skulked out of the White House.

Nixon as president was no rube, having spent eight years as vice-president, so comparisons to Donald Trump can’t be overdrawn, but the two have in common a deep chord of deviousness and dangerousness impervious to the death-by-paper-cut blandness of conventional political journalism. To grasp the Shakespearian monstrousness of these figures, the first precondition is to wake up and peel off the blinders, even if the horror of that experience might feel like taking a two-by-four to the skull.

“Some people will say that words like scum and rotten are wrong for Objective Journalism—which is true, but they miss the point,” Thompson wrote in his Nixon obit for Rolling Stone in 1996. “It was the built-in blind spots of the Objective rules and dogma that allowed Nixon to slither into the White House in the first place. He looked so good on paper that you could almost vote for him sight unseen. He seemed so all-American, so much like Horatio Alger, that he was able to slip through the cracks of Objective Journalism. You had to get Subjective to see Nixon clearly, and the shock of recognition was often painful.”

Anyone who has read much Thompson knows the point is not to wish he were alive now to write about the Trump years. He was wildly unpredictable even in his young and vital prime, sometimes blowing huge stories (like riding out the greatest heavyweight fight of all time in a hotel swimming pool in Africa). Hell, were Thompson still around and not utterly out of his mind, he might be as likely to team up with one-time Nixon stooge Roger Stone in going pure Machiavelli at Trump’s service as he would be to flail the oleaginous grifter in print. (He might have lasted two or three Scaramuccis as White House Communications Director for Trump.)

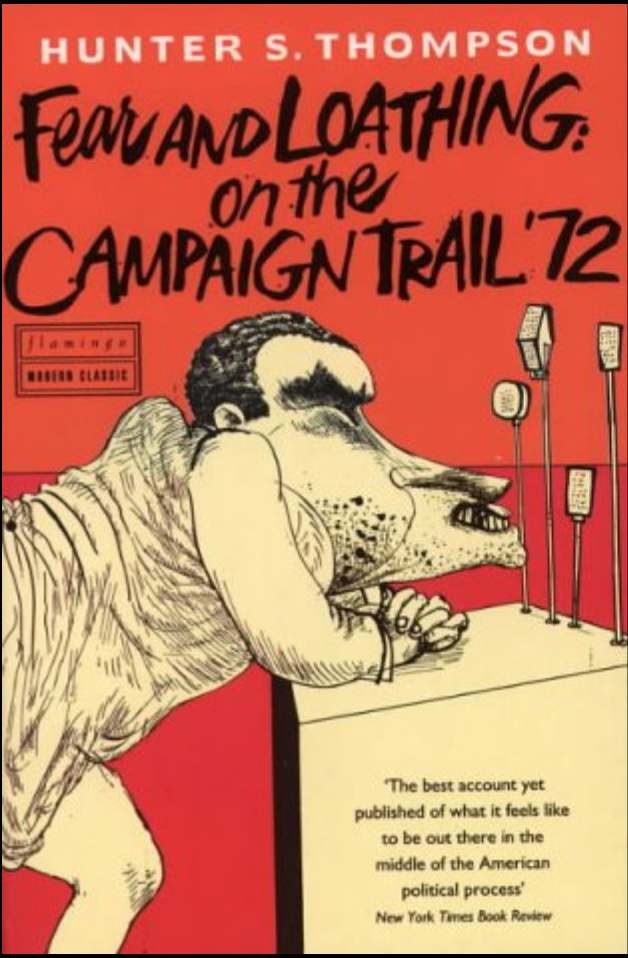

But what of spark? What of that flicker of something defiant and original and boundary-busting that illuminated Thompson’s work at its best, including his worth-a-reread first book, Hell’s Angels, written in San Francisco (and finished in a dive-y motel just off 101), and his political classic, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72?

For all the prattle over the years about the Thompson persona, for all the drug use, both prodigious and exaggerated, at its core Thompson’s writing started with radical but sensible notions about what his job as a writer should be. He believed in a combination of reporting, thinking and seeing-through-writing that could give him insights into human nature and make all subjects open to his exploration, from famous motorcycle rebels to the minutia of delegate-herding at the Democratic National Convention in Miami in 1972 (which took place in a trailer parked out back; its young staffers included a shaggy kid from Arkansas named Bill Clinton).

Thompson called his subject the death of the American Dream, but it was of course much larger than that; he explored the perils of leaning on our better selves when depravity, greed and inflamed grievance could unleash nearly infinite evil on the world. Given those stakes, conventions of “journalism” and “nonfiction” and “fiction” were almost totally beside the point, just as they are totally beside the point in understanding the current unfolding train wreck of a nation we’ve become.

RECLAIMING GONZO

So let’s have it out, for real. Let’s air out some collective vision of how courage and originality might be rediscovered in a way that bursts through the wall-to-wall white noise (think Phil Spector meets Orwell) that encircles all of us.

This Saturday in Soquel, the Wellstone Center in the Redwoods will host a wide-ranging discussion of “What Would Hunter Thompson Do?,” featuring two authors with recent books out that explore different facets of that very question: Bay Area writer Peter Richardson, author of Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo, and Timothy Denevi, who grew up in Los Gatos, author of Freak Kingdom: Hunter S. Thompson’s Manic Ten-Year Crusade Against American Fascism.

A good place to start might be the distinction between writing as calling and writing as job. Like a surfer straddling a board and peering out at the next swell, anyone who sees writing as a calling embraces the raw terror of the unknown, and musters the wherewithal to rise to the moment and come up with something fresh and original. If writing is just a job, like stuffing mailboxes with Amazon packages, then the imagination is already half-dead.

Thompson wanted to be a Great Writer, and the hilarious unlikeliness of him showing up with the Boys on the Bus to cover the 1972 Presidential election cycle for an upstart San Francisco music magazine was precisely the point. He himself was a moving target, and no one knew what to expect out of him in his regular dispatches for the magazine, which were rendered orders of magnitude more powerful by Ralph Steadman’s hallucinatory and morally serious artwork, or in the book that followed.

“I love Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail: ’72,” says Freak Kingdom author Denevi. “There’s the brilliant analysis, as well as dramatization, imagination, reflection on the horrific end to the 1960s, all of which culminates in a precisely articulated dread. Thompson could never quite come to terms with the fact that Richard Fucking Nixon, the most dishonest person at that point in U.S. history, would win by an astonishing 20 points against one of the few decent human beings ever to run for the office, George McGovern.”

Thompson hated sellouts, and railed against them with a kind of edge-of-sanity intensity that was often dismissed as mere entertainment when it should have been taken seriously, given the way that selling out has so totally taken over the writing landscape. Run a bold and original book idea by most major publishers or agents in New York these days and they’ll push a button under their desks; the next thing you know you’re in a back alley, legs hanging out of a dumpster, rubbing down the welts. “When the going gets weird,” Thompson wrote, “the weird turn professional.”

“Thompson saw sellouts as those who occupy that lowest circle of Hell: people who gave in and accepted an outcome that he spent his career in the ’60s and ’70s doing everything in his power to avoid,” Denevi says. “He couldn’t stand sellouts across the spectrum, from editors to writers to politicians to celebrities. [Edmund] Muskie and [Hubert] Humphrey sold out on the issue of the Vietnam War during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and as such he never forgave them.”

Thompson, who believed deep down that the people out there reading his stuff saw the world with the same Technicolor clarity he did, would have been beside himself trying to unleash the right combination of sharp prose, staccato sarcasm, cut-to-the-bone characterization and open satire on the dull-witted hackery of say-anything money-grubbers like Marjorie Taylor Greene and Matt Gaetz, so nakedly focused on the daily haul of online fundraising. The unhinged quality of this latest batch of political crazies would have been right up his alley.

“By no means a hippie or flower child, Thompson symbolized a new and deeply irreverent approach to American politics and culture,” Richardson writes in his excellent Savage Journey. “It was not simply a matter of shocking the bourgeoisie, as bohemians had done for generations. Rather, the Baby Boomer iconoclasm that he channeled at Rolling Stone reflected a darker suspicion that mainstream culture had lost its way and perhaps its collective mind. … It was no coincidence that lunacy became one of his major themes.”

Richardson, in summing up Thompson’s legacy, also points out the deeper roots of his work. “Tom Wolfe described him as ‘the only twentieth-century equivalent of Mark Twain,’” he writes. “Thompson’s diatribes also recalled H.L. Mencken, who railed against the booboisie, Bible-thumpers and the New Deal. But in the screeds he directed at Nixon, Thompson most resembled Mencken’s hero, Ambrose Bierce, whose ferocious invective made him the scourge of San Francisco.”

BEST COAST

This is a smart analysis that might also point toward potentially promising new ground. Richardson, a student of West Coast influence, has also authored books on the Grateful Dead, Nation editor Carey McWilliams (the one who suggested Thompson write about the Hell’s Angels), and the seminal West Coast magazine Ramparts, which helped hatch Rolling Stone. Ramparts was a big deal, bold but serious, a major jolt that inspired a generation of East Coast magazine editors like Hendrik Hertzberg of the New Republic and The New Yorker.

In 1977, Rolling Stone moved from San Francisco to New York, and founder Jann Wenner steered the once-influential publication to the silt fields of celebrity suck-up cover features. California voices have a way of cutting through the noise that East Coast establishment types often lack. Take a look at the columnists currently pushing out column inches for big papers like The New York Times and the Washington Post. I check the offerings daily, and for me a few voices stand out, notably Jennifer Rubin and Dana Milbank of the Post, and Michelle Goldberg of the Times. Others do good work, of course, but in terms of freshness, in terms of writing for themselves with some spark of animation and fearlessness, these three deliver day in and day out as none of the others do. Two of the three come from California; Rubin and Goldberg both have Berkeley degrees. (The third, Dana Milbank, as our closest contemporary incarnation of the great Mark Twain, is a kind of literary cousin to Thompson.)

Thompson’s cultural fame has led to many claims of his lasting influence on political journalism, but I don’t see it. I see a zombie war of once-fiery journalists cowed and complicit, sucking down the bile of self-hate with the easy lie that for journalism to survive at all it needs to follow the clicks, sex it up and dumb it down, and treat the serious and ominous like one more reason to smirk.

One national paper actually did a piece last week that turned the sickening journey of California’s own Kevin McCarthy into comedy—but not the good kind. Unlike, say, Liz Cheney, who torched her own political career by calling out the Trump/MAGA scam as a dire threat to democracy, McCarthy flips back and forth from Trump critic to Trump suckup—whatever it takes to angle for power. This desperate character may very well be Speaker of the House by January, and the New York Times checks in with a story letting us know that McCarthy and current House Speaker Nancy Pelosi don’t like each other very much. What is this, junior-high home room?

I’ve been a fan of impact journalism going back to my own days at Berkeley in the 1980s, joining a group that started our own weekly, and I’ve worked in New York newspaper journalism, alongside icons of brave and insightful newspaper writing like the late, great Murray Kempton and Jim Dwyer. I think the San Francisco foundation of Rolling Stone, and in turn, Thompson’s incandescent writing on politics, too often gets overlooked. I think California-style journalism mattered then and matters now. As I wrote in a New York Times Sunday opinion cover piece a few years back, “In a way, California even gave us Donald Trump. So much of his ‘training’ to be president came while he was an entertainment celebrity, on a show that, for a stretch of its existence, was produced in Los Angeles. And of course the means of his ascent—the smartphone, social media—came out of Silicon Valley. That’s a lot to have on a state’s conscience.”

Maybe in the end, the way to begin reclaiming Hunter Thompson’s legacy is to look for fresh voices from the West. Not just literary voices like Richardson and Denevi, but idea entrepreneurs, people with energy and vision to do hard things because they are worth doing. Freshness might sometimes mean quirky, and L.A.-born-and-raised National Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman talks of being a “weird child.” Weird at its best.

Publisher and author Douglas Abrams moved to Santa Cruz to follow his passion, and ended up exploring his idea that genius is a collaborative process, all about “truth hunting,” as he co-authored the bestsellers The Book of Hope with Jane Goodall and The Book of Joy with the Dalai Lama and Desmond Tutu. Maybe we need to evoke the spirit of Hunter S. Thompson to fire us up not to write a certain way, or craft a certain persona, but keep a fresh eye for new ways of truth hunting.

Steve Kettmann is a bestselling author and freelance writer who founded the Wellstone Center in the Redwoods with his wife Sarah Ringler.

The Wellstone Center, 858 Amigo Road in Soquel, will host the “What Would Hunter Thompson Do?” event on Saturday, Oct. 15 at 2pm. The conversation will includePeter Richardson, author of “Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo,” and Timothy Denevi, author of “Freak Kingdom: Hunter S. Thompson’s Manic Ten-Year Crusade Against American Fascism.” The event is free; RSVP to in**@we***************.org ” target=”_blank” rel=”noreferrer noopener”> in**@we***************.org .