![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Fish Tale:Christian Zajac fought local fishermen and environmentalists to start an abalone farm- and the battle is not over yet.

Abs of Steal

Christian Zajac's abalone dream rides the next wave of the shellfish industry

By Jessica Lyons

TEN YEARS AGO, Christian Zajac saw an opportunity to carve out a niche in the growing aquafarming business. His plan was to raise almost half a million abalone from seedlings to shellfish and harvest the popular mollusks rather than hunt them. Three other farmers planned to grow another million abalone over a five-year period.

Demand for the tasty univalve was rising, and overharvesting would soon result in a moratorium on commercial abalone diving all along the California coast. With the gourmet gastropod a swimmingly popular menu item, particularly in Southeast Asian markets, Zajac's idea had all the elements of an IPO start-up saga.

"Commercial fishing is a dying industry--that's part of the reason I want to get into aquaculture," Zajac says. "It's clean, it's not harmful to the environment, and we can't keep taking animals from the ocean. Coming into the 21st century, we've got to start thinking about growing our own food."

But the story didn't end there. The cast in this tale includes old-school fishermen and some environmentalists who fought Zajac's idea every step of the way. The result has been a seven-year struggle with the California Coastal Commission, the Department of Fish and Game and several other water-control agencies.

Last July Zajac finally got the go-ahead to anchor and operate an abalone farm in the northwest corner of the outer harbor at Pillar Point, near Half Moon Bay. The farms, operating in underwater cages, would make Pillar Point one of the nation's largest commercial abalone-farming areas.

"There are relatively few enclosed waters that have good water-quality characteristics along the California coastline that can support aquaculture, and Pillar Point is one of them," explains Fred Wendell, senior marine biologist for the California Department of Fish and Game.

Sixteen abalone facilities operate along the California coast, including one in Davenport and two in the Monterey Bay Harbor inner breakwater. Early commercial facilities started selling abalone meat in 1988. Some pioneering farmers last year began to sell cultivated pearls. Upon receiving a permit from the Coastal Commission, Zajac intended to harvest both pearls and meat at his facility, he says. But nearly nine months later, there's not a farm-grown ab in sight.

The Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen's Association (PCFFA) in September sued the Coastal Commission to stop Zajac and the three other would-be mollusk farmers.

The lawsuit alleges that the four new abalone farms will gobble up some 40 anchoring spaces--approximately one-third of the total anchorage area within the outer breakwater--which they say would violate the California Coastal Act. By approving the aquaculture permits, the Coastal Commission failed its obligation to protect harbor waters used by commercial fishing and pleasure boats, according to the lawsuit. This, it continues, would set a dangerous precedent for harbors statewide by placing aquaculture interests ahead of those of commercial fishermen.

Zajac disagrees. "I don't understand what the fishermen's reasoning is, but it's flawed," he says. "The number of salmon boats are dwindling, and the fishermen are unhappy about any form of aquaculture, which is insane. They don't want to look to the future.

"Instead of taking them from the wild, I would be raising something that is a sustainable project," Zajac continues. "The ocean can supply the kelp, the ocean can supply the oxygen and the water movement."

But several salmon fishermen and local environmentalists say it ain't so. Pointing to loss of anchorage space and environmental concerns, aquaculture critics say the abalone explosion threatens to eat up Pillar Point Harbor.

Earth Day Events: A guide to local happenings.

Ab-sent Boats

TO ZEKE GRADER, executive director of the PCFFA, the Coastal Act is perfectly clear--and supports his position.

"Facilities serving the commercial fishing and recreational boating industries shall be protected and, where feasible, upgraded," Grader reads from section 30234. "Existing commercial fishing and recreational boating harbor space shall not be reduced unless the demand for those facilities no longer exists or adequate substitute space has been provided."

"This is a clear diminution of these facilities," Grader adds. "This means 40 small business may be forced to fish on the outside [of the breakwater], risking their lives and their property. That's the main issue we are suing on."

Zajac, the Harbor District and the Coastal Commission counter that the demand for harbor space does not exist.

"When the fishermen first brought it [loss of anchorage space] to our attention, we asked for some kind of evidence, maybe a log the fishermen or the harbor master keep in terms of records," says Alison Dettmer, manager of the Coastal Commission's energy and resource unit. "The problem is, there are no records that suggest a problem with space."

Harbor officials say the need for anchorage space tops out at 200 boats during summer holiday weekends. But fishermen insist that the harbor holds between 400 and 500 boats during seasonal peaks.

Because Pillar Point is the only protected harbor between San Francisco and Santa Cruz, and a refuge from winter storms, the proposed abalone farm threatens fishermen's safety, says Robert Miller, a commercial salmon fisherman and the chair of the Vessel Safety Committee of the PCFFA.

"I don't want to lose one boat or one fisherman," Miller says. "That's a hell of a lot of lives to put in danger so that people in Japan can eat abalone."

But San Mateo County Harbor Master Dan Temko counters that the PCFFA's argument holds no water. "With the size of the commercial fleet that we are currently getting at the harbor, I don't see loss of anchorage as a problem," Temko says. "The only time we've ever seen the anchorage fill up is during peak anchorage periods in the summer, usually holiday weekends, when we have a lot of yachts and commercial fishing boats." He adds that salmon season, between May and September, coincides with warmer weather and fewer storms, making it safer for commercial boats to anchor outside the breakwater.

The farms also represent a potentially lucrative cash cow to the harbor district, which stands to earn up to $70,000 a year in fees.

The mollusks turn a profit for the abalone farmers as well, bringing in up to $25 each to wholesalers. Zajac, however, says he wouldn't see a profit for at least six years into the operation.

Raised from seedling to the marketable size of three inches, the shellfish take three years to grow. And even then, "you don't get much money for a three-inch ab," Zajac says--only about $6. "Cheap labor in China, Australia, Mexico means that the abalone are going to sell cheaper from those places--and they don't have the protesters."

Murky Waters

LITTLE IS KNOWN about the environmental impact of abalone harvesting. Some environmentalists say the abalone will devour too much kelp and dissolved oxygen in the water, stripping the San Mateo County Harbor and the Monterey Bay kelp forests.

According to Coastal Commission estimates, the four farms will require between 2.7 and 4.3 tons of kelp per day to feed the voracious little critters. Each ab consumes about 5 percent to 10 percent of its body weight daily.

According to the farms' permits, the four farmers can only harvest kelp from designated "opened," or licensed, beds. Fish and Game officials argue that the rate of kelp-bed reproduction--about 100 tons per acre, per year--ensures no adverse effects on the habitat. Local environmentalists disagree.

The extra kelp required to feed the abalone could triple the existing regional demand, says Vicki Nichols, executive director of Save Our Shores. This will further add to the use conflicts between local divers and commercial kelp harvesters, Nichols says, because this is where many of the harvesters are anchored.

"It's [Santa Cruz] kelp beds that are going to be hit," she argues.

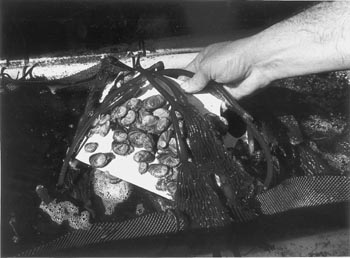

Abs Gone Bad:San Mateo County fishermen say these farm-grown mollusks threaten the native species of Pillar Point.

All that eating has another, predictable result. Fishermen worry that the abs will produce too much fecal waste, poisoning the fish and crabs along the harbor floor, which has proved to be a problem for East Coast fish farms.

Between the four facilities, the abalone will excrete about 60 percent of what they eat.

"These ab farms will be dumping about 2.6 tons of fecal waste [a day] into the outer harbor, which will effectively eliminate even more harbor space," says Duncan MacLean, a former president of the Pillar Point Fishermen's Association. "Trying to get out of the harbor because of that much dung is really going to create a shitty mess."

Fish Out of Water

CRITICS ALSO SAY the delicate shellfish have the potential to spread disease, such as the foot-withering syndrome, a deadly bacterial disease that causes mollusks to starve to death, and parasites, such as the sabellid worm, that attack native animals that live in the harbor.

Peter Grenell, general manager of the San Mateo Harbor District, says that one of the major concerns is that the abalone could cause a sabellid worm infestation in shellfish, similar to an outbreak in the early 1990s in which the parasitic worm spread to every abalone aquaculture facility in the state. The previously unknown worm was introduced into California by abalone seed imported from South Africa. While the California Department of Fish and Game has stepped up efforts to eliminate the parasite, departmental programs have yet to eradicate it.

According to Wendel, the four abalone farms do not pose a threat to the harbor because of low-risk conditions at Pillar Point and because the four new facilities must use "sabellid-free" abalone seed, a condition of the Coastal Commission permits.

"The environment on the bottom of Pillar Point harbor is a very soft-bottom environment," Wendell says. "It's not conducive to a crawling worm seeking a new host, and there are a very low number of host species [on the harbor floor]. The permitees are under a condition to only use seed from a certified sabellid-free seed source, and those factors combined suggest a very low risk level."

According to permit rules, the four aquaculture facilities will be tested regularly for withering syndrome and to monitor the dissolved oxygen levels. "And both the Harbor District and the Commission can order operations stopped immediately if there are problems, according to the conditions of the permits," Grenell says.

But after fighting since 1993 to obtain the necessary permits from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Department of Fish and Game, the Regional Water Quality Control Board and the Coastal Commission, the PCFFA lawsuit to stop his farm may be the breaking point, Zajac says.

"I'm ready to give up," he says, sitting on his boat, the Serena May, on a sunny Thursday afternoon.

"I spend 200 days out of the year on the ocean. I've been fishing here for 15 years, and a lot of knowledge comes from being out there. We fishermen spend so much of our time on the ocean, and it really irks me when people read books and call themselves environmentalists and think fishermen don't know anything. I'm 38 now. I don't know if I will have the backbone to harvest kelp when I'm 50. Trying to fish commercially and start an abalone farm is too much."

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by George Sakkestad

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Photograph by George Sakkestad

From the April 19-26, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.