Santa Cruz County has long been at the forefront of progress, both in California and the nation. Mainland surfing in the U.S. originated here (sorry, Huntington Beach), the area used to be renowned for its agriculture, and the logging industry brought lumber mills and flumes to the Santa Cruz Mountains.

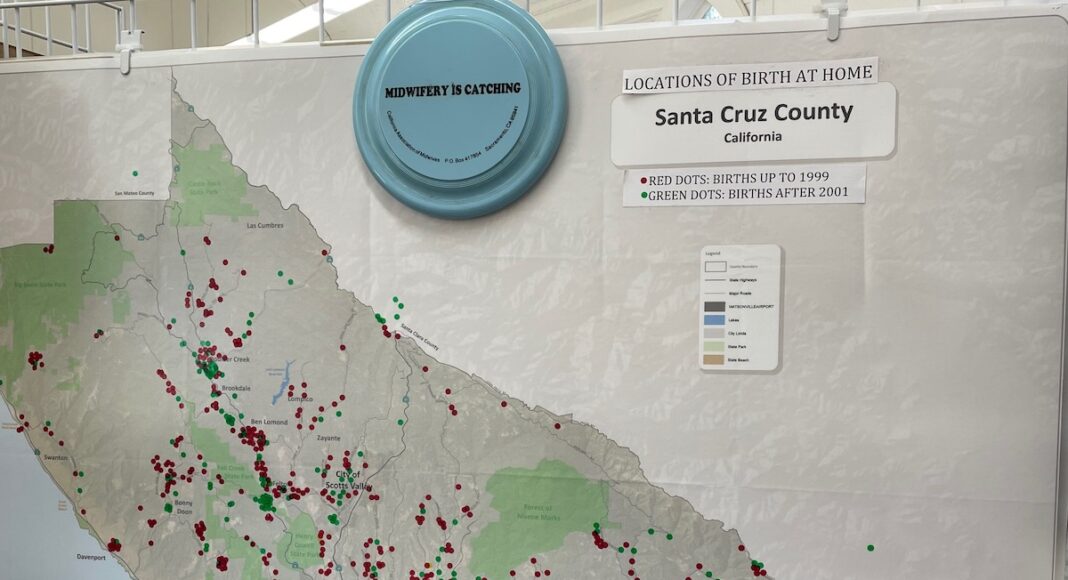

In celebration of “National Midwifery Week,” which runs from Oct. 3-9, the San Lorenzo Valley Museum is celebrating and honoring yet another startup in Santa Cruz County: the midwifery industry. Midwives around the world have worked tirelessly to provide comfort and care to mothers and babies alike, and the current exhibit at the museum, “Birth Happens,” collects memories, art and artifacts from the area’s midwives. The exhibit provides stunning insight into the struggles and successes of midwifery in the Valley.

Lisa Robinson, Board President of the San Lorenzo Valley Historical Society, was honored to finally deliver the goods on this display. Elected in 2008, Robinson has made it her mission to bring the past to the present, allowing tourists and locals alike to revel in the rich history of the San Lorenzo Valley, and its impact on the current day.

Robinson started curating the exhibit in 2016—that’s when the “Birth Happens” project did a pop-up exhibit at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, and Robinson harkened back to her own experience with home birth.

“There were so many pieces of the display that I knew nothing about, and the origins of the project emanated from the San Lorenzo Valley. I thought it was so interesting, and the stories needed to be told,” she said.

Robinson and her team started from scratch, interviewing midwives, collecting data and stories from as far back as the 1800s.

“The events of that time actually fed into the stories of the 1970s, and the exhibit pays tribute to those women who led the industry,” she said.

In creating the exhibit, the group collected oral histories of midwives who worked in Santa Cruz County, and written submissions from others. In Robinson’s view, the exhibit is meant to explain the relationship between the midwives and the doctors and examine the difference between having a baby in a home environment and a hospital. Robinson’s group talked to people like Raven Lang and Linda Walker who helped create the Birth Center of Santa Cruz in 1971, and women who were arrested for being midwives, like Kate Bowland.

Bowland is a firecracker of a woman with white hair, gentle eyes and steady hands. She grins as she reminisces about the babies she has “caught” and the price she has paid for her dedication to her craft. In 1974, following a phone call from a man who purported to have a wife in labor, two midwives from the Birth Center responded to what was reported as an imminent birth in Ben Lomond. The two attending midwives—Linda Bennett, and an apprentice, Jeanine Walker—were caught in a sting operation; there was no pregnant woman, and no baby on the way.

Once they arrived at the cabin, their birth kits were confiscated, and they were arrested for practicing medicine without a license. Agents then raided the center itself, and Bowland was taken away in handcuffs, but not before contacting the media during her arrest. Bowland was determined to push the envelope for her colleagues and ended up taking her case to the California Supreme Court. In 1976, the Bowland Decision was handed down from the court. The result? Lay midwifery was defined as an illegal practice of medicine. Ironically, there was no path for midwives to become licensed at that time, although home births attended by midwives were legal until 1917 in the state. In 1949, the State of California stopped issuing midwifery licenses, leaving activists like Bowland striving for reforms decades later.

Since 1976, massive changes have made their way through the tunnel of midwifery licensure. There are now two different certifications for midwives: a California Licensed Midwife and a Certified Nurse Midwife. Certified midwives are not required to hold a registered nursing license, while California Licensed Midwives are licensed and regulated by the Medical Board of California.

Andrea Humphrey, 35, is a new addition to the Santa Cruz Mountains and is eager to get into the local midwifery game. A Nurse Midwife at Dignity Health, she has spent years working with international organizations like Doctors Without Borders, and in faraway locations like Togo, South Sudan and Nigeria. She graduated in March 2020 from the University of Washington with a Doctor of Nursing Practice in midwifery, landed in Santa Cruz County and sees her future opening before her.

“Midwives are trained in a different school of thought than an obstetrician. We work in a team, and it’s a dynamic environment when you have a midwifery idea of a physiological birth with the backup of an obstetrician, knowing that we can provide emergent care quickly, and that our collaboration allows us to work in higher-risk scenarios,” she said. “It’s important for the community to know that when they are seeking that level of care. So far this model of collaboration is the most ideal, and has the best possible outcome for mother and baby.”

Women like Bowland are thankful for the influx of new talent in the area.

“The seeds of midwifery came from women wanting to take care of their bodies in ways that were not part of standard medicine. In the 1960s and 1970s when women gave birth, they were drugged, tied down to the hospital bed, shaved and immediately separated from their babies; maternal death rates were at precariously high levels,” she said. “Midwives were marching in the streets, demanding more attention be paid to making prenatal care accessible and affordable.”

As a result of the midwives’ efforts, maternal death contracted by 50% in California. The Nurse-Midwifery Practice Act was passed in 1974 (the same year Bowland was arrested) after lay midwives had been protesting the legislature for 11 years, demanding a path to licensure. The complaints about lay midwives operating with art and drama degrees finally made sense to lawmakers, and so the Act was passed.

Bowland finally had the opportunity to attend midwifery school in 1975 at UC San Francisco, although she admits that a “midwifery school without walls” had been operating in Santa Cruz County for years.

“The San Lorenzo Valley was really the beginning,” she said. “We influenced the whole country.” Bowland estimates she’s performed over 1,100 home births in her career—“home births take a lot of time”—and she’s allowed herself to think with retirement.

“I stopped in 2015, but in 2020, with the shutdown, the phone rang off the hook, so I went back into it,” said Bowland, who finally retired this year after 50 years of catching babies.

Feeling a little pressure to learn more? The “Birth Happens” exhibit runs through Nov. 21, and can be found at the Felton branch of the San Lorenzo Valley Museum, 6299 Gushee St.