In the dance world, the Jabbawockeez are iconic: the men in the white masks who revolutionized hip-hop. They made performance about the body, about the beauty of the whole, and about the power of one small isolated movement that, when it ripples through an entire migrating bird formation, knocks the breath right out of you.

“If you ask any mainstream choreographers under the age of 35, the Jabbawockeez were a huge influence to all of them,” says Pacific Arts Complex (PAC) co-founder David Bortnick. “One of the members, Jeff ‘Phi’ Nguyen, said they can ‘kill it without killing it,’ meaning you can be really soft and together and that synchronization takes the place of the power of the move.”

Their name is synonymous with a kind of egalitarian hip-hop that negated the need for a “lead dancer” and elevated the art form to new heights.

What most people don’t know, even locally, is that at the core of the Jabbawockeez revolution was a Santa Cruz dance legend, the late Gary Kendell.

“Gary Kendell is who I would credit with bringing real street dance, hip-hop and hip-hop culture into Santa Cruz, into the studio and onto the stage scene,” says Carmela Woll, a local employment law attorney who co-founded the dance studio Motion Pacific in 1998. “I won’t say no one else came to Santa Cruz and did hip-hop, but he seeded a generation of kids who grew up to be teachers and performers.”

He was magnetic, says Woll. Kendell, known as “Gee” to his students, was raised in Seaside, and at the time he led Santa Cruz’s small but powerful hip-hop scene, says Woll. It was around 1990, when Woll was a math teacher at Santa Cruz High School with no formal dance training, that she took one of Kendell’s dance classes at the local studio All the Right Moves.

“He was hip-hop, one hundred percent,” Woll remembers, adding that he was born to an African-American father and Korean mother. “It wasn’t something he put on for class, it was how he dressed, the music he listened to, the people he hung out with, it was the whole culture. It wasn’t just a dance form.”

When All the Right Moves closed, Woll and a handful of Kendell’s other dedicated followers decided a space was needed to continue his work. Woll left her teaching job to become Motion Pacific’s director, opening the studio with fellow dancers Greg Favor and Molly Heaster.

Kendell began teaching at Motion Pacific, amassing a following and cultivating new talent while he continued to perform around the Bay Area.

In the early 2000s, Kendell and Randy Bernal, who were a part of the San Jose group MindTricks, joined forces with the Sacramento trio Three Musky (who performed with the trademark white masks and gloves). In 2003, what started out as an attempt to form a San Diego-based chapter, turned into the Jabbawockeez.

Kendell died at the age of 37 in December 2007. In March 2008, the Jabbawockeez won the $100,000 grand prize on the MTV show, “America’s Best Dance Crew” with six members instead of the intended seven.

“From my perspective the scene really deflated,” says Woll, of how the Santa Cruz hip-hop dance culture changed after Kendell died. There are plenty of classes for kids, she says, and people like Harold McCord and Bortnick are inspiring young dancers today, but it’s sparser for adults.

“Even those he taught as kids who’ve gone on to teach—and I’m so grateful that they’re keeping it alive and teaching what they learned—but to me, he was the heart and soul of hip-hop dance in this community,” Woll says. “I’m obviously biased, people might debate with me.”

Living the Legacy

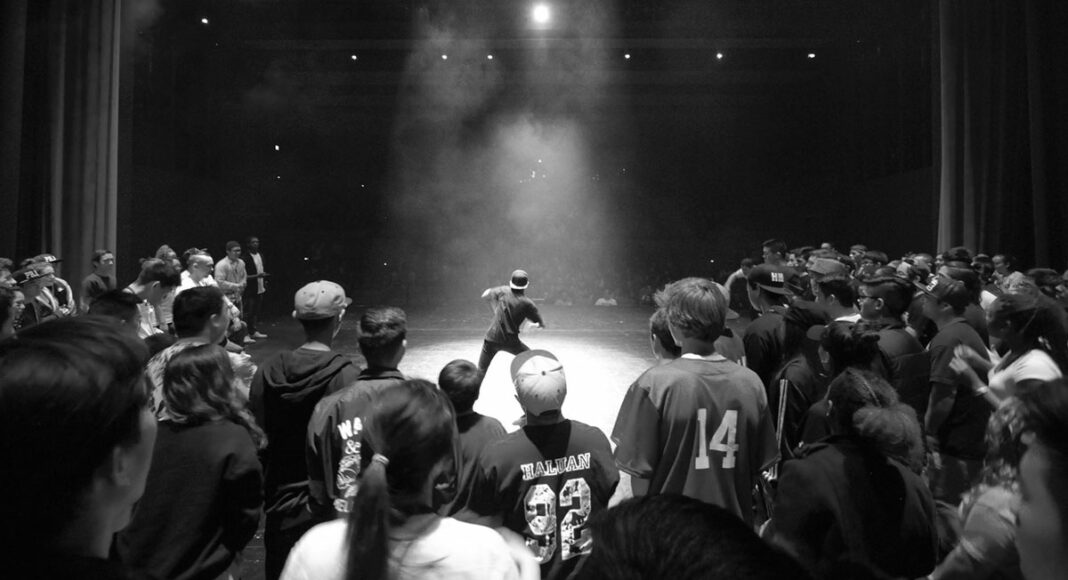

There’s a moment in their dance piece when the UCSC competitive hip-hop dance team Haluan drops into a V-formation: the outside line sinks to a crouch, the inside group stays upright. They bend in the knees, shoulders follow their heads to the left, with their right arms straight in front of them, ridin’. This is the moment when you see the music, it’s the moment you see the power of the whole and how innovators like Kendell made this kind of dance possible.

The kind of hip-hop network that thrived here during Kendell’s day doesn’t exist anymore. That’s why Haluan’s members are rehearsing at midday on the top floor of the only real parking structure on campus, in preparation for the En Route Urban Dance Showcase on April 30. Sweating in the first sunlight of spring, and with all 40-something bodies moving in unison to 50 Cent’s “Disco Inferno,” it’s a fierce kind of energy.

That kind of energy is a crucial ingredient to creating your own hip-hop showcase, especially in a town where the enthusiasm has dwindled, says Ray Chung, one of En Route’s first coordinators.

“We wanted to connect Haluan and the larger Santa Cruz community and the rest of the Bay Area, hopefully, even the rest of California,” says Chung, who has since graduated and now unofficially helps from the sidelines. “We wanted it in town so that outside communities could see what’s happening here.”

Showcasing 16 groups from up and down the Golden State’s coast—some collegiate, some medleys of teenagers and adults—strutting their finest moves, En Route returns to Santa Cruz on April 30 for its second coming. It was an effort of labor and love, says Lauren Korth, 21, a senior at UCSC and a Haluan director, and although the dance team operates under the umbrella of the Filipino Student Association, it requires not only self-motivation, but also a lot of self-funding.

“Something that people don’t always realize is that people are paying to perform for you,” says Korth. “There are very few ways that dancers make money now unless you’re in a professional ballet company or want to do it commercially in Los Angeles, or by chance are good enough to be in Jabbawockeez and win ‘America’s Best Dance Crew.’”

Haluan creates choreography as a collective, with all of its members pitching moves that may or may not make it into the final piece. It’s fitting, says Korth, because Haluan translates into “mixed” in Tagalog, and every dancer brings a little of their own flavor to the final production.

“It’s just passion and drive to be better dancers and make your dance group better, being the best you can—there’s nothing else behind it,” Korth says. “We do it because we love it and we want to put on a good show.”

Being geographically cut off from the Bay Area makes it difficult to connect to the thriving scene over the hill, says Chung.

Granted, Santa Cruz is not exactly an urban hub. With the African American population at barely above one percent, it’s no wonder that a dance form that historically came out of black urban street culture didn’t have the cultural clout to establish itself in a sleepy beach town.

It’s something that Bortnick, whose advanced hip-hop team, Kinetik, will perform at En Route, felt first-hand when he performed with Kendell. Bortnick was 8 years old when Kendell did a lunchtime show in the cafeteria of Branciforte Elementary School. Kendell took Bortnick on as a mentee and toured with him and another student.

“I was the only white person in the room in a huge majority of the classes I took—not in Santa Cruz, but when I would follow Gary around the Bay. For a long time, the Asian presence was underrepresented in the media, but they were a huge driving force in hip-hop in the Bay,” says Bortnick of the period when he’d perform with Kendell as a child in the ’90s. “But what was really awesome is that [ethnicity] really doesn’t matter. If you have it, you have it. Your dancing is going to speak louder volumes about your authenticity than your race or your socioeconomic background. It’s one of the things that I love most of the hip-hop culture. Your image as a dancer is so much less important than your ability. Ability just reigns supreme.”

Sound and Vision

“Randy Bernal, one of the founding members of the Jabbawockeez said, ‘Be the music, so I can see the music,’” remembers Bortnick, who also puts on the Gee Fam Dance Convention every summer in honor of Kendell.

Hip-hop in the early ’90s was an altogether different art form from what it is now, says Bortnick, who toured with Kendell in his early 20s with a patchwork of dancers who would later form the Jabbawockeez.

“At the time there was a tendency to not ignore the music, but to ignore the subtleties in the music—so the music might go boom, boom, kah, but the choreography would go boom, boom, boom—it would be on beat, but not exactly match,” Bortnick says.

“[Kendell] was a breaker, and he had tricks, but what he was really known for was the ability to make you see the music in visuals,” says Bortnick. “You listen to this music and you would hear it once but you would never hear the little cowbell in the background, but then you’d see the dance to it and he would accent it and you would see the things you’d never heard.”

Bortnick doesn’t claim that Kendell was necessarily the only one doing that kind of movement, because hip-hop was destined to go in that direction. But at the time, he says, it was mind-blowing.

Those kind of small, subtle isolations of the body gave rise to a new kind of competition style, one focused on musicality and nuance rather than keeping things at a maximum energy level throughout an entire performance, says Haluan’s Korth.

Korth grew up doing competition dance in various genres, where the goal was ultimately to make it to Los Angeles. She says that since she competed as a child and teenager, hip-hop has moved away from the individual to the group.

“It’s less about how much fun you look like you’re having, and more about the movement itself,” Korth says.

There’s been a rapid transformation over the past decade, Korth and Bortnick agree. Groups like Haluan aren’t competing to be on MTV, says Korth—although Justin Bieber featuring YouTube breakouts Keone and Mariel Madrid in his music videos was a huge thing for the community—in general, they just want to be YouTube famous.

“YouTube is a game changer because someone can put something that is really emotional and raw and it’ll get 20 million views and suddenly it’s not a fringe thing anymore,” says Bortnick. “When I was growing up, you compared your crew to the crew down the street or the studio down the road. Now everybody is compared to the best dancers in the world because it’s all at the tip of your fingers and that can be really, really hard.”

Getting Schooled

It’s the rapid dissemination that has new styles popping up almost every day and academia hasn’t caught up.

“I dont think there’s a rubric for it,” says Micha Hogan, 27, who was born and raised in Santa Cruz and remembers the days of local hip-hop troupes like BoomSquad in the early 2000s. “There are styles to teach, but with ballet it’s a style and there are critiques and techniques that have been handed down for hundreds of years since it started. If you want to do hip-hop, it’s now in gyms.”

Hogan went all over to pursue a dance education, including to Columbia College in Chicago, but no matter where he went, he would only see hip-hop outside of the curriculum—unless it was a “dance appreciation” day in class, he says.

Hogan is now a dance teacher at PAC and Motion Pacific, but like Bortnick he didn’t finish school because it just didn’t make sense to.

“One of the problems is that there is a lack of affluent, well-educated degreed people in the [hip-hop] community. And you can’t teach at a college unless you have a master’s or a Ph.D. You’re really not going to find a hip-hop choreographer with a Ph.D.,” says Bortnick. “There’s no justification for spending all that money, be spat out of school, and be behind all the people who didn’t go to school and spent all that time auditioning.”

It’s weirder still, because hip-hop is everywhere, says Hogan: “Hip-hop is pop culture.”

“Everyone wants to learn hip-hop, few people are like ‘I want to be a ballerina for the clubs, I want to go to clubs in San Francisco and kick people in the face!’ What do you do at the club? Hip-hop,” says Hogan.

It’s the perfect time, then, says Bortnick, for an event like En Route to bring Santa Cruz back to its roots.

“Hip-hop classes on college campuses now leave much to be desired, but hip-hop crews on campuses, like Haluan, are flourishing. They’re phenomenal,” he says. “It’s something that Santa Cruz really needs right now.”

Hip-hop is chipping away at the walls of academia, says Hogan, and it’ll get there because at its core, it’s a dance form that allows redefinition.

“It’s body rolls, it’s isolations, it’s hip movements. When you’re by yourself and you’re grooving, you’re moving to the beat—that can be classified as hip-hop,” says Hogan. ‘It’s hard, it’s edgy, it’s emotionally driven. Hip-hop is embedded in you, it’s an attitude, it’s a style, it’s a sense of being.”

En Route From All Over

Hosted by UCSC’s Haluan Hip-Hop Dance Troupe, the second annual En Route Urban Dance Showcase will feature performances by: Barkada Modern (West Covina), Boogie Monstarz (Sacramento), Choreo Supremacy (Salinas), Dynamic Street Rockers (Watsonville), Haluan Hip-Hop Dance Troupe (Santa Cruz), Homebound (Merced), INSA Dance (Irvine), Kinetik Crew (Santa Cruz), Lsf LiveSan Francisco (San Francisco), Main Stacks (Berkeley), Mobility Dance Crew (Davis), reDEFINE (Union City), Str8jacket (San Mateo), Squadratic Formula (Bay Area)

Team Velociraptors (Berkeley), the PROJECT co. (Sacramento), Wild Ones Dance Co. (Los Angeles)

Info: 6 p.m., Saturday, April 30. Cabrillo College Crocker Theater, 6500 Soquel Drive, Aptos. enroutesc.com. $15-$20.