[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he early months of 1866 were auspicious for the California coastal community of Santa Cruz. A proposed new road along the city’s western cliffs promised “one of the most beautiful drives in the vicinity” as it wound its way toward “the Seal-rock and the high cliff, with the rolling waves breaking in foamy view.” Downtown, the Pacific Ocean House—the community’s first luxury hotel, replete with 100 rooms, expansive gardens and croquet grounds—was offering special “winter arrangements,” with room and board for as little as two dollars a day. The hotel promised “well furnished tables, and clean, comfortable beds.”

The Santa Cruz waterfront was teeming with activity. Several Portuguese whaling companies were operating in the region, from Pescadero down to Carmel, while Chinese fishermen along the Central Coast salted and prepared several hundred thousand tons of fish for export.

Three-masted schooners carried passengers and supplies up and down the coast to a pair of wharves on the waterfront. In March, it was announced that the steamship S.S. Senator would make two stops a week in Santa Cruz, on its regular run along the Pacific Coast.

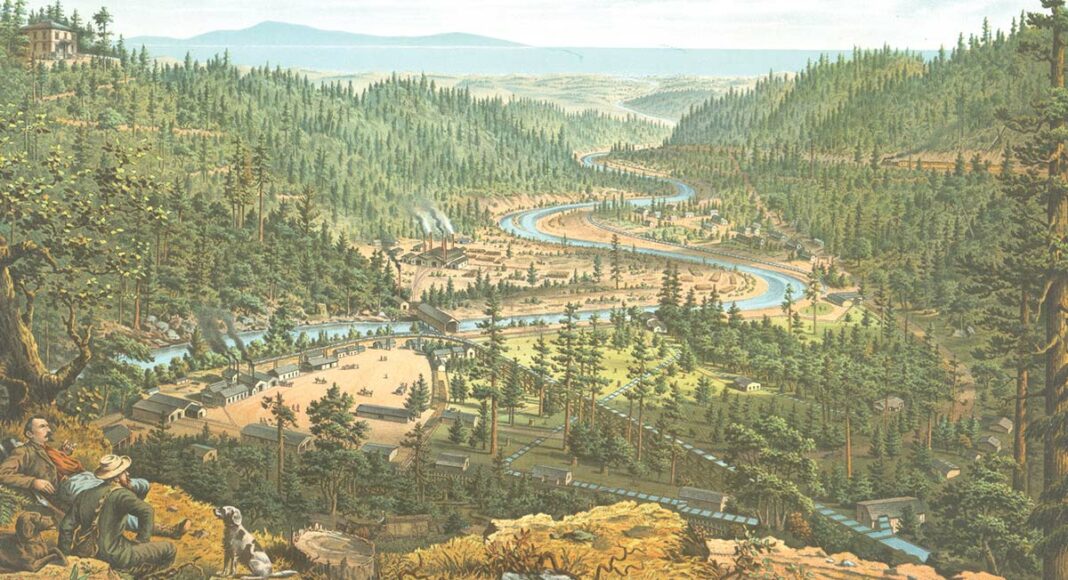

The Santa Cruz Mountains were also bustling. Nearly 20 saw mills were producing more than nine million feet of redwood lumber annually. A toll road from Felton down the San Lorenzo River to the Davis & Cowell lime kiln operation above Santa Cruz was being debated in the California legislature. Six-horse stage lines from San Jose brought visitors and prospective residents over the Santa Cruz Mountains; the journey took nearly a full day.

But for all the enterprise in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Santa Cruz was still a relatively remote Western outpost of the American empire, a place where basic municipal services like police and fire protection were hodgepodge affairs at best. Water supplies and sewage disposal were rudimentary and often health hazards. Justice was still delivered through the barrel of a gun—or the end of a rope.

Santa Cruz County had roughly 5,000 residents in 1860, with men outnumbering women by more than two to one. The community of Santa Cruz, as it was loosely defined, had a population of approximately 1,000. It was a rough-and-tumble town. Nearly half the community’s 57 businesses were saloons or brothels. While the city was teeming with kinetic energy and big dreams—lime kilns, paper mills, tanneries, lumber yards and the California Powder Works were all in operation—Santa Cruz remained geographically isolated and economically shackled by the absence of a railroad connection and a cohesive civic government.

All of that was about to change.

At the state capital in Sacramento in the spring of 1866, legislators passed the Registration Act that called for “the registration of the citizens of the State, and for the enrollment in the several election districts of all the legal voters thereof.” Less than two weeks later, at the end of the legislative session on March 31, the legislature passed a “special act” that formally approved the incorporation of the “Town of Santa Cruz.”

On May 3 and 4, voter registration took place at the offices of the Santa Cruz Sentinel. Only two days later, on May 6, citizens of Santa Cruz carried out one of the requirements of the legislation, going to the polls to elect the township’s first “trustees”—brick mason George C. Stevens, merchant and hotelier Amasa Pray, and grocer S.W. Field. Two months later, on July 23, 1866, Congress approved an act which allowed for the township to allocate deeds of trust for those properties presently located on federal lands previously claimed by Mission Santa Cruz and the adjacent pueblo of Villa de Branciforte.

It was a lot of political and bureaucratic paperwork, but amidst all of the paper shuffling, a city (or something at least approximating a township) was born.

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]o what is it, precisely, that we are celebrating with a lavish 150th birthday party (see sidebar) that includes a multitude of events, including musical performances and fireworks at the Main Beach this Saturday? It’s a bit of a complicated story.

Human history in this region dates back more than 10,000 years, and Native Californians claimed the lower reaches of the San Lorenzo River watershed as their home for millennia (they possibly called it Aulinta or Chamalu). The name “Santa Cruz” was first attached to the place in 1769, when the Gaspar de Portolá expedition gave the rubric to a small stream (likely Majors Creek) just west of the San Lorenzo. The name was formally given to the Franciscan mission founded here by Padre Fermin Lausen in August of 1791, which was the “birth date” traditionally celebrated by the community for more than a century.

The secular pueblo to the east of the San Lorenzo (inhabited by retired Spanish soldiers, or invalidos) was given the name Branciforte, which it kept for more than a century. For a brief period after the demise of the missions and Mexican independence from Spain, Santa Cruz was actually called Villa Figueroa, named after a popular Mexican governor.

That didn’t last long. With California’s admission to the Union in 1850, our county was briefly called Branciforte County before adopting the name of Santa Cruz in April of that year. The name of the county seat was now known permanently as Santa Cruz. It looked like a town and squawked like a town, but it wasn’t quite there yet. It had yet to be incorporated.

The movement to incorporate the Township of Santa Cruz began as early as the 1850s, when two of the community’s most prominent business members and largest land owners, Frederick A. Hihn and Elihu Anthony, pushed a proposal for incorporation at a meeting of approximately 60 local residents in February of 1857. But the majority of a committee charged with investigating the prospects “deem[ed] it impractical under any circumstances, to incorporate the town or village of Santa Cruz.” Hihn and Anthony’s “minority report,” which favored incorporation, was shelved and the meeting adjourned “until the town grows larger.”

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the early 1860s, during the height of the Civil War (California, of course, was a free state and Santa Cruz was predominantly, although not entirely, a pro-Union community), Hihn picked up the incorporation cause once again, this time by himself. In January of 1864, the Santa Cruz Sentinel (then a weekly paper) first published an editorial noting that “it is likely that a bill will be presented to the Legislature this winter to incorporate the town of Santa Cruz.” The Sentinel opined that without such a bill, “no adequate means can be taken to prevent or extinguish fires, to restrain nuisances, or to improve the village, without an incorporation.”

But the editorial also cut to the chase about the driving force of incorporation: scores of residents in the community had laid claim to lands that were still under the control of the federal government—tracts that were “formerly included in the ancient Mission of Santa Cruz [generally west of the San Lorenzo River] and the pueblo of Branciforte [lands east].” By presenting an incorporation bill properly to Congress, the editorial continued, “that body would undoubtedly grant back these pueblo [and mission] lands to the town of Santa Cruz. The trustees of the town could equitably apportion them. The proceeds of the sale of the lands would furnish means to begin an improvement of the town … hence the necessity of incorporation.” Hihn drafted a preliminary version of the incorporation bill—one that included 14 articles—that was eventually sent to the state legislature.

An early Santa Cruz merchant, civic presence and one of the county’s largest landowners, Frederick Augustus Hihn, was a dominant force in the economic and political affairs of 19th century Santa Cruz County (and all of Northern California, for that matter). The German-born “capitalist,” as he was later to be identified in the Great Register of Santa Cruz County Voters, developed one of the city’s first mercantile stores at the juncture of Pacific Avenue and Front Street (at the site of today’s Flat Iron Building); he developed water companies throughout the county; established roads and railroads; and was the founder and initial developer of Capitola. In 1869, he was elected to the California legislature. At the time of his death in 1913, the Santa Cruz Morning News described him as a “man of energy and progress, who made things come his way when they persisted in going the other.”

In 1864, at the time he reinitiated the incorporation effort, Hihn was serving on the County Board of Supervisors. He had been endorsed by both the Union (Republican) and Democratic parties, and had the strong support of Duncan McPherson, the editor of the Sentinel. “Mr. Hihn, as a Supervisor, has always commanded the respect and friendship of his conferees,” McPherson declared, “because of his inexhaustible fund of information concerning every portion of the County and every branch of business in it, and because of his great ability as a business man, his integrity and his indomitable industry.”

Hihn was not, however, a figure without controversy, particularly in South County. While one Watsonville Republican acknowledged that Hihn had come to the county “poor and destitute” and had “by his own acts … risen to a prominent position among the businessmen of his county,” others viewed his political efforts, particularly those aimed at incorporation, as driven by self-interest. Wrote one critic by the nom de plume of “Civis”:

The Santa Cruz Incorporation Bill, drawn up by Supervisor-Judge [sic] Hihn, providing that a tax shall be levied upon the people of Santa Cruz for his benefit, will not pass the Legislature … We have pretty well shown up his system of voting himself extra money in the Board; of voting money to improve his property; of securing himself as a defaulting bondsman …We bow, but not willingly, to the late decision of the Supervisor-Judge, the great Tycoon.

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]ihn’s initial proposal called for the township to provide water and fire services; to elect trustees who were to serve single-year terms, as well as a “town treasurer” and “town assessor”; to “prevent and remove nuisances”; to license and regulate various economic activities—including “public shows, lawful games and the sale of spirituous liquors”—and “to provide for the impounding of swine and dogs.”

Hihn’s draft boundaries only extended as far east as the middle of the San Lorenzo River. It included boundaries similar to those today on the northern and western borders, but did not include the local waterfront. The Sentinel protested: “The main objection that we have is that the limits of the proposed incorporation is too small. We have in our hearts a big town, and cannot be satisfied with a small one. The bounds of the incorporation ought at least to go to the ocean. We don’t like the idea of going out of town to get to the beach.”

The Sentinel explained the primary purpose of the incorporation movement—to facilitate clear land titles to those properties that had long been occupied by residents of the county following the demise of Spanish and Mexican rule, including the lands of Mission Santa Cruz (west of the San Lorenzo River) and the pueblo of Branciforte (east of the river).

There was one problem: Hihn’s critics proved triumphant. Too many viewed his efforts as those of someone all too eager “to fill his hungry pockets.” The region’s representative in the Assembly, Alfred Devoe (who was from Watsonville) wrote a letter stating that he would report the bill back to the legislature when he had “heard from the people of Santa Cruz.” A “remonstrance” with more than 200 signatures was sent to Sacramento opposing the incorporation. The California Legislature never took up the 1864 version of the bill.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]wo years later, in 1886, the annexation cause was taken up again, this time without Hihn’s name attached. Richard Cornelius Kirby, born in England and a longtime tanner in the community (he was a noted “Black Republican,” opposed to slavery), completed a draft bill of incorporation—very similar in form and content to Hihn’s of two years earlier, albeit with a few significant tweaks) that was eventually sent to the legislature for passage. This time, the boundaries extended all the way to the waterfront and a short distance east of the San Lorenzo river bottom (although Branciforte and Seabright would not be annexed to the city until the early 1900s).

Santa Cruz being Santa Cruz, the incorporation legislation did not proceed to Sacramento without opposition—and no small amount of vituperation. There was less public debate the second time around, and the Sentinel published little about the effort. Apparently those opposed to the annexation sent another “remonstrance” against the bill to Sacramento, though this time it had far fewer signatures. According to one letter writer, a “petition was signed by all our prominent citizens, with very few exceptions.”

Those who opposed the bill were dubbed “gophers” for not keeping their efforts “above ground.” They had resorted to sending their letters to the Pajaro Times, in Watsonville, where Hihn and the editors of the Sentinel were held in disdain.

After the legislation was passed—but before the inaugural election was held in May—a counter-slate was formed of those opposing incorporation: dairyman Horace Gushee, and merchant Franklin Cooper and one candidate identified simply as “Smith.” The pro-incorporation forces won the election, according to a tally reported in the Sentinel, by an “average majority of 40 votes.” The so-called Gopher Party was forced back underground.

Progress, or so it was dubbed, had triumphed. By June of that year, a survey map listing all of the city’s land ownership was completed; a few months later, the U.S. Congress granted title to those lands which had remained under public domain. Property investments were protected. Downtown Santa Cruz almost immediately doubled in size. Streets were realigned and renamed (Willow Street, for instance, was changed to Pacific Avenue). The county courthouse was constructed on Cooper Street. In only a few years, the City of Santa Cruz would swell to a population of 2,500. Industry and commerce were on the rise, and various railroad lines would be constructed throughout the region in the 1870s.

By the fall of 1866—precisely 150 years ago—Santa Cruz was, quite literally, a city on the verge.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]ncorporation, however, did not a perfect community make. In spite of the establishment of local legislative bodies and courts, justice could still take the form of vigilantism for those outside the town’s predominant Yankee power structure. Californios of native and Mexican descent, freed African American slaves, Chinese and Southern European immigrants were all marginalized—socially, politically and economically.

By 1866, there were two small Chinese communities in Santa Cruz—one located at the California Powder Works, along the San Lorenzo River just north of town (today’s Paradise Park); and a second on what was then Willow Street (todays’s Pacific Avenue), between Walnut Avenue and Lincoln Street. For the next two decades, they would be the subject of fierce racism and vitriolic attacks, more often than not led by the Santa Cruz Sentinel.

As local historian Sandy Lydon notes in his seminal work Chinese Gold, in the spring of 1864, a masked and armed group of vigilantes attempted to herd the Chinese residing at the Powder Works back into Santa Cruz. “If they [the Chinese] get blown up in the powder mills,” the Sentinel opined, “it will not be much loss to the community.” Their fate was only to grow uglier in the years ahead.

As bad as it was for the Chinese, native Californians had it even worse. In the 1860s, there was still a surprisingly sizable community living on pasture lands formerly owned by the Mission, known as the Potrero (what is today Harvey West Park), which had been provided to them by the Catholic Church for work rendered at the mission.

An article headlined “Lo! The Poor Indian” in the June 23, 1866, Sentinel noted that: “When the Santa Cruz Mission was established, the tribes of Indians at Aptos, Soquel and Santa Cruz numbered nearly 3,000. All are now scattered or have passed away; their tribal character has become extinct—except about forty, who have their houses on the Potrero, within the limits of our incorporation … Would it not be well for the citizens of Santa Cruz to now determine that the Potrero … shall be forever set apart to those Indians and their children, and that no vandal shall ever despoil them of what the good priest gave them for services rendered.”

It certainly would have been “well,” but by November, the Sentinel noted that the Potrero property, “occupied in part by Indians,” had been sold to a local dairy farmer. Those surviving moved east across the river to Branciforte, which came to be known as “Spanish Town” and where many of the community’s original families still resided, often in abject poverty.

Incorporation came with a price attached. Best that we not sweep it under the rug. It’s a reminder for us all to aspire, in the words of Abraham Lincoln (assassinated less than a year before Santa Cruz became a municipality), to the “better angels of our nature.”

One hundred and fifty years after incorporation, Santa Cruz is a bustling city with a diverse economy, hosting a major university, a vital downtown business community, a series of arts centers, a public beachfront, a magnificent coastal walkway, a historic downtown, and one of the largest wooden wharves of its kind in the United States. Santa Cruz has survived devastating earthquakes and calamitous fires, violent floods and disastrous droughts—always to rebuild and prosper once more with the critical assistance of a municipal government charted 150 years ago.

Perhaps those who founded the city a century-and-half ago would be surprised (if not awed) by its present complexity and grandeur, but they would also be content in knowing that the basic municipal infrastructure that they established 150 years ago—a democratic, service-oriented civic government—continues in place today. The local democracy they created remains a process, imperfect as it may be. The task is ours to sustain it.

Special thanks to Stanley D. Stevens, coordinator of the Hihn-Younger Archive at UCSC, for providing relevant Hihn materials for this story.

Really enjoyed your article on Santa Cruz history. I belong to the Santa Cruz Parlor No. 26, Native Daughter of the West. Our Parlor was established March 17, 1888 and we are still a very active group.

Our seal was created by Charles M. Madeira, an artist, “who tried to depict the great beauty…of California.” This was probably done in the late 1888 and I have tried to find out information on this artist. Do you know anything about him or where I could get information.

I am the quasi-historian of our Parlor. Thank you. Jeanne Thompson

Good stuff! My great aunt was born in Santa Cruz, 1880s I believe. Her father helped to build one of the wharfs I am told. They were mostly Scottish. My father was Portuguese from Easy Bay area.