A world once comprised of baking-soda volcanoes and potato-powered light bulbs, the science fairs of today are filled with fierce innovation and competition.

They’re also—as 8th grader Rinoa Oliver learned through a recent math and science project—replete with privilege, now more so than ever.

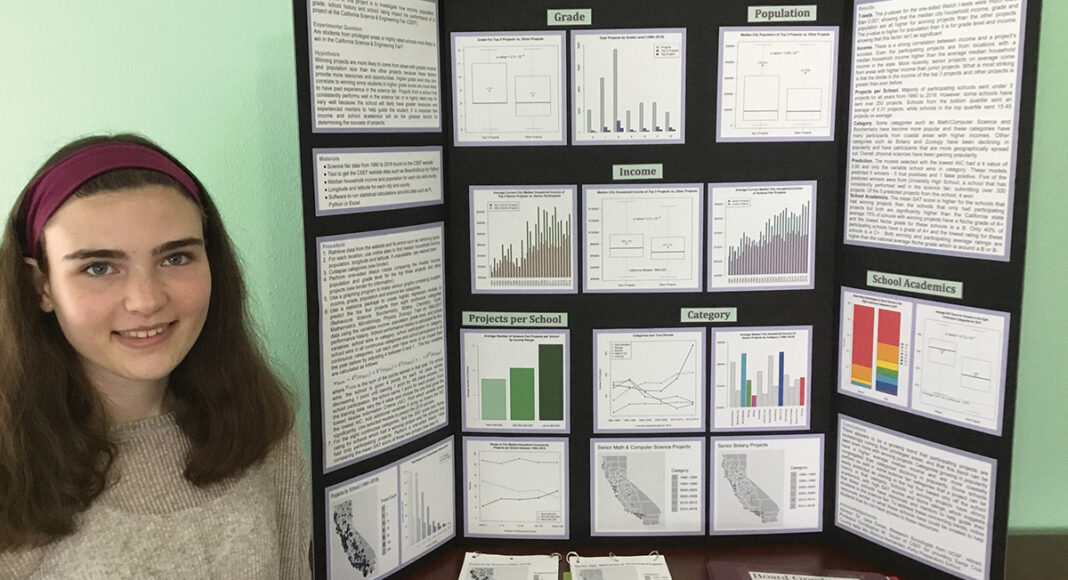

The 13-year-old got the inspiration for her project at the awards ceremony for last year’s California state science fair, where she spotted a troubling trend. “I noticed a lot of the winning projects were from wealthier areas, such as Orange County, and I wanted to investigate further,” she says.

Rinoa started analyzing 29 years of California Science and Engineering Fair results, and found that students from wealthier areas are far more likely to produce winning projects than those from poorer regions. Plus, schools who’ve produced winners in the past are more likely to do so again.

Rinoa’s work is gaining serious recognition. She beat out thousands of applicants to earn a top-30 spot in this year’s Broadcom Masters national middle school STEM competition for projects in science, technology, engineering and math. Later this month, she’ll travel to Washington, D.C. with the other finalists to compete for over $100,000 in prizes, and the title of the top young STEM student in the country.

“I’m really happy. I think it’s such a good opportunity,” says Rinoa, and she’s excited to bring more attention to equity issues within STEM fairs. “I think it’s really important to study, because by knowing about these concerning trends, you can help address them.”

The Society for Science and the Public puts on the Broadcom competition each year. To Maya Ajmera, the society’s president and CEO, Rinoa’s findings are unsurprising. “I think she’s spot-on with her results. I mean, I think her mathematical modeling is really terrific, but the outcome does not surprise me,” says Ajmera.

In an effort to combat these inequities, the society has implemented several programs aimed at supporting students living in “STEM deserts,” high-poverty areas where access to high-tech resources tend to be limited. This includes the Advocate Grant Program, which provides training and year-round support to mentors working with underserved students to encourage them to participate in STEM competitions.

Still, according to Rinoa’s research, the problem is only getting worse.

On the local level, disparities aren’t much better. Rinoa looked at schools in the 95060 zip code, which stretches from Bonny Doon through much of Santa Cruz. Out of all the zip codes in the county, that area had the highest participation in the state science fair. Meanwhile, no school in Watsonville, which has a lower median income, had more than 15 projects entered.

“I’ve been really fortunate to have these opportunities, and I think it’s really sad that other people might not have them,” says Rinoa, noting that both her elementary school and her current school, Georgiana Bruce Kirby Preparatory, are in the 95060 zip code.

At Kirby, students who participate in STEM fairs are offered a “faculty sponsor to guide or scaffold their work toward an outcome that they agree upon together,” says Christy Hutton, head of the school. Tuition at Kirby costs around $30,000 per year, although about one-fifth of students receive some form of financial aid. Kirby students also receive in-school aid, including things like loaned technology, software and instruments, as well as one-on-one teacher support.

“A lot of attention is paid to ensuring that no student is barred from participation in any activity by their economic circumstance,” says Hutton, adding that tuition assistance is the second-largest item in Kirby’s budget after personnel costs.

Rinoa says she’d like to see the advantages she’s had at Kirby be shared among students of all economic backgrounds. Currently, the young scientist is working on doing just that.

Last month, Rinoa gave a presentation to the Santa Cruz County Office of Education about the local inequities she found through her project. Now, she’s working on a website to provide science fair resources and assistance to students across the country.

“Doing these projects has really showed me how much I’m interested in science and using it to help people,” says Rinoa.

Hutton says that the middle-schooler “has an exceptional way of seeing the world.”

“It’s remarkable that a student of her age has the self-discipline and capacity for communication that it takes to bring her ideas to life,” she adds. “I feel very fortunate to have her in the Kirby community.”

Each of the 30 Broadcom Masters finalists has received a $500 dollar cash prize, and an all-expenses-paid trip to D.C. for the final competition. For the first time ever, 60% of this year’s finalists are female. Rinoa says she’s excited to meet the other finalists and learn about their projects.

“It’s definitely inspiring to see other girls that are doing science,” she says.

I think you mean “inequity” (unfairness), not “iniquity” (evil).

To add, a little late, to Rinoa’s statement of unfairness in the academic playing field in math and sciences now evident in Santa Cruz schools, private in particular. I worked at GBK from 1998 to 2004, first as office secretary and before leaving, as school registrar. During those six years, I saw differences in what wealthier kids enjoyed compared to their classmates. Rinoa didn’t mention clothes worn and accoutrements such as late model cell phones, laptops and Northface or Patagonia backpacks. Also not mentioned were textbooks, chem and art lab supplies, assorted fees and for those who could afford it, a class trip. These kind of different strokes for different folks have an immediate impact with the academic advantages as Rinoa mentions coming a close second. Now, with the COL in Santa Cruz having reached a skyhigh level, the differences between the advantaged and disadvantaged classes must be staggeringly painful.

Great interview of the 8th grade science fair winner and her teacher! The article seemed to miss the point, however, when starting to talk about “hi-tech deserts.” Read closely the interviews with the student and teacher – the student’s project is about income disparities. The teacher talks about how each kid at Kirby school has a “’faculty sponsor to guide” their work – meaning personal attention and just what the teacher stated, “guidance”, which are essential to making a kid feel good about themselves and helping them learn to develop ideas and eventually be successful on their own. These benefits are not gained from interaction with a device. Sure, technology can benefit older kids, but interest in science and math starts way earlier – blossoming creativity and love of learning and observation skills start very early in kids. Poor communities may be challenged due to fewer school resources resulting in lower salaries, lower teacher to student ratios and teachers stretched thin, while on the home front likely all parents are working, sometimes multiple jobs, with migrant families in our communities as well. This is how financial strain can contribute to lack of personal attention and guidance. I do not think that “lack of access to high-tech resources” is the real problem here. Providing “year-round support to mentors” as later mentioned in the article seems like the way to go! Best inventors start by using their creativity and figuring out ways around limitations!