The fish on one’s plate has been on a wild journey—but not “wild” in the way people use the word to indicate something natural or untouched. Humans have gotten involved, and, as we know, humans complicate things.

Thousands of years ago, fishing was relatively simple: a few hunters, a village to feed, a nearby body of water, a spear, a fire, a meal. In the globalized economy, however, one fish often passes through countless hands over thousands of miles from the moment of catch to the grocery store shelf. The human and environmental tolls along the way are about as unfathomable as the ocean itself, in large part because traceability in these environments is an enormous challenge. The best available data on the average can of tuna, for example, often associates the fish inside with over 100 vessels.

The Santa Cruz nonprofit FishWise has become a major player in worldwide efforts to improve data collection and bring full accountability to the seafood industry. Their work ranges from international waters, to Monterey fisheries, to local New Leaf stores. As the organization closes out its 20th anniversary year, its members are celebrating the progress they’ve made and looking ahead to all there is left to do to bring safety and sustainability to local waters and the high seas.

A Slippery Situation

FishWise began in 2003 when Teresa Ish and Shelly Benoit, two UCSC students in the graduate level Ocean Conservation Class, ran into a problem at a grocery store near campus. “They recognized that there was little to no information available for customers to determine whether seafood was sustainable or not,” says Senior Project Director Michelle Beritzhoff-Law. The students are now celebrated as FishWise’s co-founders. Ish’s graduate advisor, UCSC Professor Emeritus Marc Mangel became an early champion of the organization and board president. “That’s really how FishWise started, by working with a local retailer, New Leaf Community Markets, to collect information about the seafood products—where a fish was harvested, with what methods—informing them what was sustainable and what could be improved upon and then labeling it in-case so that a consumer could make an informed decision,” she says.

That mission is much easier said than done because the sea defies easy quantification from almost every angle. As the complexity of the issues they faced became apparent, FishWise grew rapidly.

“You are at the whim of nature as soon as you get out on the ocean,” says Beritzhoff-Law, “and then you are dealing with a wild resource. You can’t see the fish or the crabs or whatever it is you’re harvesting.”

Beef might come to mind as an industry that could provide some models given similar concerns about sustainability there; but ranchers have clear fences delineating property lines and the ability to own, count and trace their stock. Imagine trying to brand a fish. Sara Lewis, FishWise’s Traceability Division Director, explains, “They are parallel industries in terms of being proteins that are widely consumed, but they are not parallel in terms of how they are managed at all, because fishing is the last hunter-gatherer, the last competitive source of food.”

It’s not that there aren’t any laws. On international waters, intergovernmental groups called regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) attempt to monitor their shared resources through treaties based on consensus. Though some vessels want to comply with these regulations, many still take advantage of the anonymity the ocean provides. Illegal methods abound: fishing without a permit, fishing in closed-off areas, fishing with destructive gear like dynamite and cyanide. It is estimated that 90% of fish populations are currently fished at, or above, sustainable limits. One notorious vessel—The Thunder—was known to use nets measuring up to 45-miles long, which caught all manner of endangered species as bycatch throughout a decade’s worth of illegal fishing that totaled $67 million in profits.

Furthermore, vessels often conscript (or traffic) those desperate for work into dangerous conditions akin to indentured servitude or debt bondage. Approximately 50 million people work at sea, and the most vulnerable among them deal with piracy, torture, harassment and brutal murder at the hands of nefarious sea captains.

U.S. territorial waters have much stronger fisheries management than the high seas, “but they are still out there, and there’s not always someone right next to them watching everything they’re doing,” says Lewis.

A culture of confidentiality—which some call “the maritime merry-go-round”—does not help matters. “No beef rancher is really all that worried that someone might know his ‘secret spot,’” says Lewis. Many seafarers, by contrast, profit off keeping their sources to themselves and balk at the idea of increasing transparency in their trade.

(Fish)Wise Mind

Today, FishWise provides environmental and social expertise to major U.S. and global corporations, including Albertson’s Companies (which owns Safeway), Target, as well as companies based in the E.U. and Japan. FishWise staff frequently work with the seafood directors and buyers of these companies to collect the supply chain information necessary to drive decision-making, developing interactive dashboards the companies can use to monitor progress toward sustainability goals. The programs FishWise is developing and implementing with companies are positioned within a unique intersection of business interests, marine conservation and human and labor rights advocacy.

“We take a three-pillar approach to achieve our mission,” Beritzhoff-Law says. “One is direct supply chain engagement, where we work directly with companies and their supply base. The second is collective engagement, and the third pillar is focused on governance reform.” Working across these pillars, FishWise often illuminates the ties between environmental challenges and social challenges in the seafood industry.

Beritzhoff-Law emphasizes that the issues FishWise tackles are so broad that collaboration between many stakeholders at a time is key. Facilitating those connections, FishWise is creating tangible change within the industry.

“A new thing more and more companies are looking to do is not just, you know, if they find an issue, stop supplying from that vendor or that supply chain, but really remedying the situation and working to provide resources to those impacted workers and making sure the situation improves,” she says.

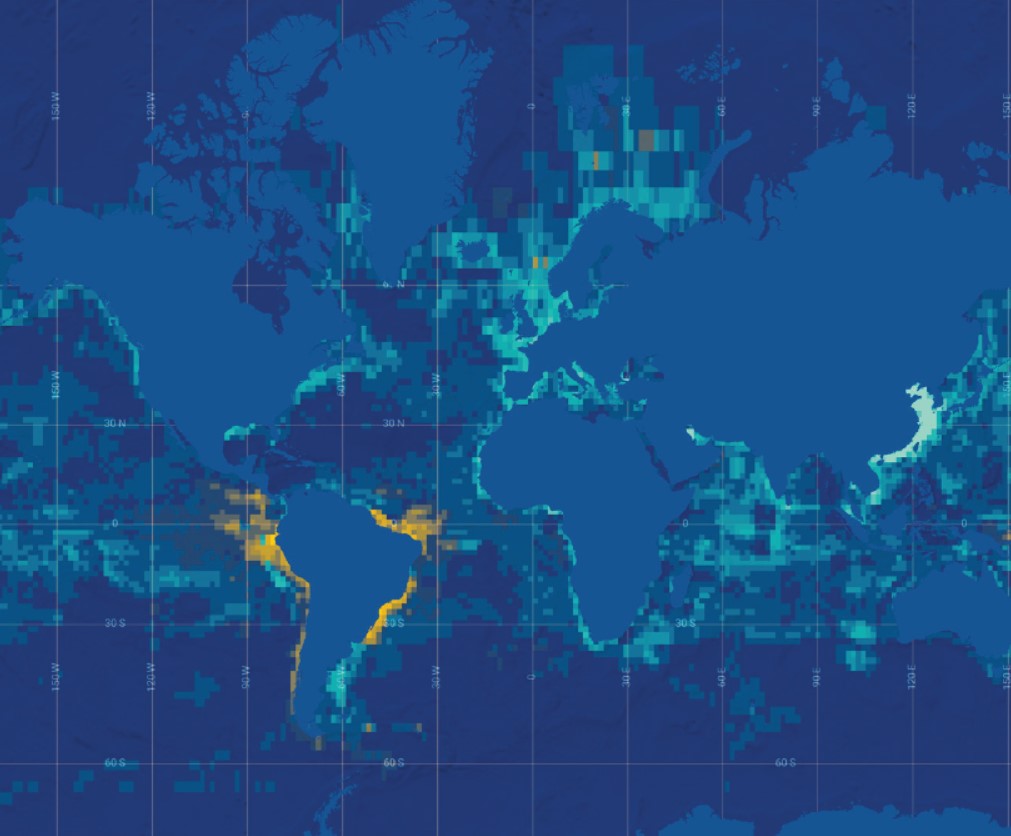

Over the past two decades, rapid change in technology has given FishWise new tools to do this work. In 2016, Google in partnership with Oceana and SkyTruth launched the website Global Fishing Watch, which uses satellite data to allow anyone with Internet access to watch the hundreds of thousands of vessels at sea in near-real time. About 200,000 vessels at any given moment agree to publicize their location, but the map also reveals countless “dark vessels” in the water. Whether identified or not, it is not rare for a vessel to veer into protected waters; or to be at sea for a suspicious amount of time, which indicates the fishers aboard may be held there working against their will. As recent documentary projects like Seaspiracy and The Outlaw Ocean have illuminated, such rogue vessels are, quite literally, floating prisons. Among many shocking reports, there have been reports of workers being beaten with stingray tails and thrown overboard when ill.

All of this to provide a can of tuna certainly gives the consumer pause, even if they are not inclined to worry about the ethics of eating the fish itself.

The Next 20 Years

Returning to the aforementioned can of tuna, the good news is that there aren’t different fish going into each can. “The fish might not have come from 100 places,” says Lewis, “but the challenge is the way that data is collected about which vessels possibly could have contributed to that can. It’s an aggregation problem where you have let’s say 10 vessels that land tuna all in one location, and then that’s sometimes frozen, and they wait around for a while, and then they can it.” In the time between docking and canning, 100 other vessels could have easily stopped by the same facility to drop off their own catch to the same freezer. In the past, if managers knew anything at all about who caught the fish in the can, it was only the list of possible vessels.”

FishWise is pushing for more specificity, and they are succeeding. A major breakthrough came in 2022 when their retail partner Hy-Vee, a midwestern grocer, became the first major retail company ever to publicly disclose a complete list of vessels supplying its tuna.

“If you can get information about the actual vessels that are in your supply chain—the fishing vessels that collect the fish—if you can identify those and have that information flowing through your supply chain,” Lewis says, “you can use really amazing data tools to perform risk assessments to help ensure that those products were legally harvested and to understand risks to the laborers, like the fishers on board.”

In February 2023, the organization announced its new Executive Director, Jenny Barker, M.P.A. With an extensive background implementing fisheries management programs around the world from Honduras to Cambodia, Barker is an ideal leader to guide FishWise into the future.

“FishWise has grown to hold a unique and important role in the sustainable seafood movement over the last 20 years,” Barker says. “We will continue to promote comprehensive sustainability–for social, environmental, and economic benefits.”

Some ongoing projects include the Roadmap for Improved Seafood Ethics (RISE), a publicly available eLearning resource that reached 2,325 users in 88 countries in 2022. The organization also has leveraged its traceability and social responsibility expertise to consult with government agencies in both the U.S. and in other seafood-producing countries, including Peru, Ecuador, Tanzania, Vietnam, and Japan.

Though its efforts take it to the most far-flung locals imaginable, FishWise has Santa Cruz at its core. It continues to partner with New Leaf grocery stores around the city and also maintains close relationships with groups that support local fisheries, including the Monterey Bay Fisheries Trust, Real Good Fish and Ocean to Table, among others. Many of its members are avid surfers and ocean-lovers, Santa Cruz locals who understand the allure of the sea—as well as its dark side. Their work, on a simple level, aims to bring the beauty and serenity Santa Cruzians enjoy in waters just off the city’s coast to the places where the ocean represents the opposite of freedom.

“We started here,” says Beritzhoff-Law. “We really feel connected to this community.”

FishWise is a non-profit 501(c)3 whose mission is to sustain ocean ecosystems and the people who depend on them by transforming seafood supply chains. To make a tax-deductible donation to support FishWise, please visit fishwise.org/donate

Good coverage! FishWise deserves local and national support for their valuable work.

Is FishWise involved and/or aware of proven technology solutions to the whale/turtle dungeness crab trap entanglement problem and delays in experimental gear application in the California dungeness fishery caused by California State enforcement officials?