I can almost smell smoke as I stare at one of the photographs on display in Frans Lanting’s westside studio. Deep orange flames swallow a hillside next to the ocean, and thick smoke blacks out the sky. It’s a photo from the 2020 CZU fire.

“We were engulfed by it,” says Lanting.

“Chris and I live in Bonny Doon. And we nearly lost our own home. But we banded together with neighbors to fight off the fire.”

He motions to the photo.

“This is a scene that I captured at Waddell Bluffs the night when the fire exploded. That’s the night when Swanton and Last Chance got hit and Big Basin was completely destroyed. I never thought we’d see something like this, where the fire literally came down to the beach.”

I ask him how he kept his composure.

“As a photographer and as a storyteller, of course, I wanted to be there. But in the back of my mind was, ‘We really need to retreat to make sure that we’re not going to lose our home.’ So it was a really harrowing night, as it was for many people.”

The photo is part of the “Bay of Life” project. Lanting, an internationally renowned National Geographic photographer, set out with his creative partner and wife—National Geographic writer and videographer Chris Eckstrom—to document the area that’s been their home for more than 30 years. The project includes stories about iconic wildlife and endangered species, as well as the voices of local farmers, fishers and foresters.

A book collecting photos and text from the project, also titled Bay of Life, was published last month, and Lanting and Eckstrom are now preparing for a presentation at the Rio Theatre on Nov. 12 and an exhibit at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History in January. They walk me through their studio, and we pause at a photo of whales feeding.

“This is the cover of the book, and a signature image for the project,” says Eckstrom. “Lunging humpback whales with anchovies spilling out of their mouths and gulls circling above. The subtitle of the book and presentation is “From Wind to Whales.” And that is because when the northwest winds kick up in the spring, they push away the surface water, and cold upwellings that are nutrient-rich rise to the surface. That nourishes phytoplankton and zooplankton and everything up the food chain that then leads to the whales that come in summer for that bounty of fish and krill. So we look at this as a seasonality: from wind to whales.”

“What makes Monterey Bay so unique is that we have this abundance of marine life in close proximity to the environment where we all live,” says Lanting. “There are very few places on the planet where you could capture this kind of scene this close to the shoreline. See in the background, we have all the built-up infrastructure. There’s agriculture. There’s residential development. You can see the hills of Aromas there. And yet, there’s this extraordinary scene of humpback whales feeding collectively.”

We continue moving through the studio, passing bobcats, elephant seals, jagged Big Sur coastline and more humpback whales, eventually settling at a desk to continue our interview.

GT: Are all these images from the last few years?

FRANS LANTING: The majority. There are some historical images in the book because I’ve been making photographs in Monterey Bay for as long as I’ve lived here, which is more than three decades. One of the images shows a historic gathering of Monarch butterflies from the 1980s, when there were more than a quarter of a million at natural bridges. And now they’re down to maybe just one or 2,000. So that perspective back in time is one of the dimensions that we’re covering in the book. There’s also historical images by other photographers in the book that go back almost 100 years, from the period when the Santa Cruz Mountains were clear-cut and the bay was plundered for marine mammals and for fish, and so on. And that’s part of the story as well.

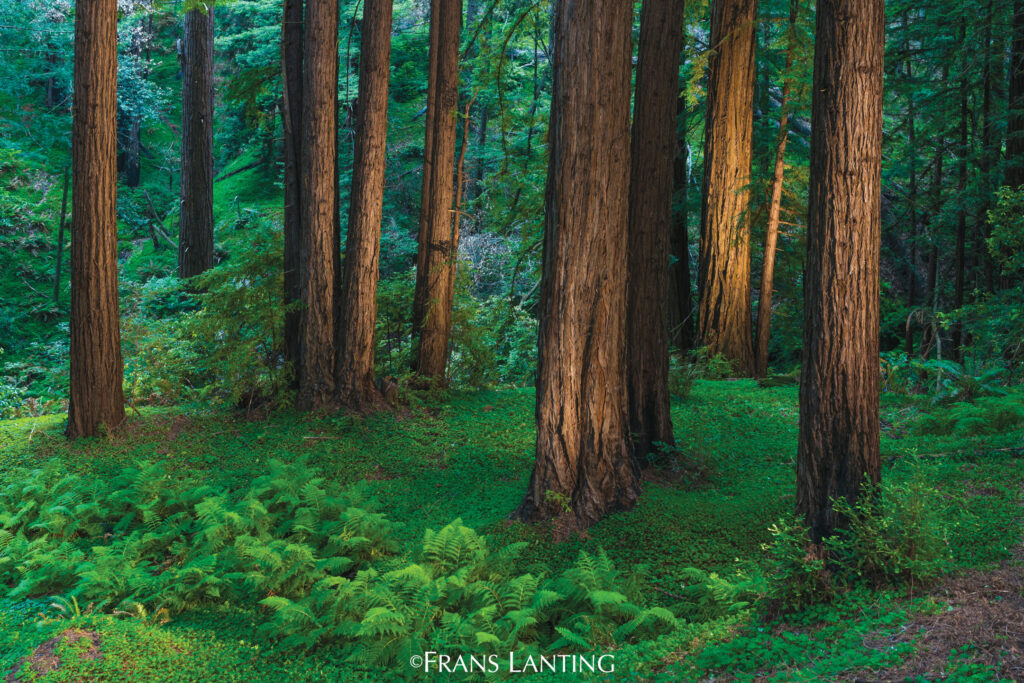

CHRIS EKSTROM: A century ago, this was an ecological disaster area in many ways, with the fish depleted and the forest clear-cut, and marine mammals virtually gone. So it’s quite remarkable that we’ve had a period of restoration and resurgence of life. The forests have grown back, the marine life has returned and marine mammals are back. It’s an incredible story that tells you what can happen when people put their minds to making change.

FRANS LANTING: Because it didn’t happen automatically. Nature’s resilient, but people have really made the recovery happen through activism, through legislation, through education, through research. It became a really powerful success formula that enabled the bay to thrive again.

You’ve partnered with several local conservation groups for this project. How did you choose who to work with?

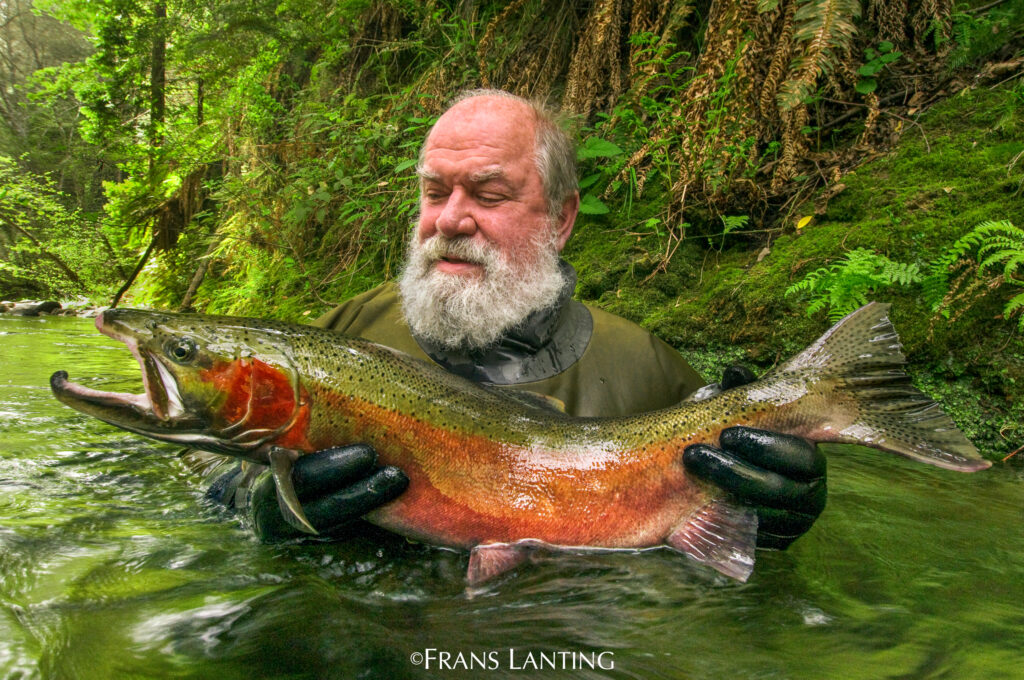

FRANS LANTING: With a number of them, we’ve had long working relationships. We’ve long supported the Seymour Marine Discovery Center, because we’ve done benefit presentations in partnership with them. The same with the Natural History Museum. With others, we really wanted to cover their fieldwork: The Predatory Bird Research Group, which has been responsible for the comeback of the peregrine falcon here. And the Monterey Bay Salmon and Trout Project. It’s a long list—there’s two dozen of them listed in the back of the book. For the event at the Rio, we reached out to half a dozen of them that are important for the educational outreach that we are planning in connection to the exhibition at the MAH. We’ve invited them to join us on stage at the Rio on November 12, and we’re going to announce some exciting new programs.

What else will you be doing at the Rio event?

CHRIS EKSTROM: We’ve done benefit presentations for the community for more than 25 years at the Rio Theatre. Sometimes we’re telling a story about a project we’ve worked on at National Geographic. But this year, we’re telling the story about Monterey Bay—about home—which is really exciting to us. And we present a show with stories, images and videos, and then we have a brief lightning round with our partners at the end of the show, and a Q&A.

FRANS LANTING: We haven’t been able to do one in three years because of the pandemic. So we really look forward to reconnecting with people in the community. And anyone who comes to the Rio will be invited to join us for an extended conversation via Zoom, because we have a lot of things to share. And we think it’s going to lead to quite an extended conversation that we can’t accommodate in the course of just one show. We’re also going to announce new plans for a Bay of Life charitable fund that we’re establishing with the Community Foundation Santa Cruz County. Chris and I are going to kickstart it with proceeds from the event at the Rio.

You’ve taken photos and videos of amazing scenes all around the world. What’s different about documenting home?

FRANS LANTING: You have to almost pretend that you see this place for the first time. Because when you are curious and you have a sense of wonder about what’s in front of you, that is often a really good starting point for becoming enthusiastic and becoming creative.

CHRIS EKSTROM: You think you know your home until you start to cover it and document it in the way that we are doing. And then you discover that you really have hardly scratched the surface. We reached out to a lot of different scientists and naturalists and connected with them. And they taught us so much that we thought we already knew. Going out with herpetologists and finding crazy salamanders under rocks and in streams, and going out with the ornithologist to search for the marbled murrelet nest fledge—there were so many moments like that that we never experienced until we covered home.

FRANS LANTING: We also reached out to people who have a deep understanding of what it takes to be a farmer, or a fisher or rancher or a forester here. Because to us, it’s important that their knowledge and their point of view is part of this bigger story.

What were the biggest challenges in documenting all this?

FRANS LANTING: The challenges are farther inland. We created a map of all the protected areas in the larger Monterey Bay region. And you can see there’s a lot of them. But they kind of peter out when you get into the Salinas area, and then there’s not much in the Salinas Valley area. And that is a discrepancy that provides a need and an opportunity for new initiatives. Because we feel that every community needs to have places to go where families can take their kids within a reasonable distance. We are blessed along the coast to be able to do that. But not so much in Gonzales or in Salinas, or in Soledad or in Greenfield. And to us, this is all part of the Monterey Bay.

CHRIS EKSTROM: So much of the Salinas Valley is private land. And people don’t have access to the river except at a couple of points, where they can get down to the banks and actually be in a protected place. We want people to look at the Monterey Bay region as a whole, as a bay of life and feel that they are part of the region as a whole.

FRANS LANTING: It’s not just this narrow strip along the coast. The future of the sanctuary will be determined in part by what happens upstream. So what happens in the Salinas Valley really is very important. And that’s why we are defining Monterey Bay in part by the watershed. And the activities of people inland need to be part of this.

What do you see as the biggest issues currently facing the Monterey Bay area?

FRANS LANTING: Monterey Bay—the way it is now—shows that we can heal damaged ecosystems. And that’s really important for people around the world to know, because we’re dealing with this everywhere. There’s very little pristine nature left on the planet.

But looking forward here in Monterey Bay, we know that there are big challenges because more and more people are moving here. So we have population growth to deal with. We don’t know what’s going to happen to our water supplies. In an era of climate chaos—it’s not just climate change; it’s climate chaos—the weather is becoming more and more extreme. In our vision, we define the Bay of Life this way. We created a logo and scripted a credo: “The Bay of life is a unique confluence of land and sea, energized by the sun, shaped by the forces of fog and fire and influenced by the actions of people.” And it’s these dynamic influences of fog and fire that we think are going to reshape our quality of life here. We know what’s happening with fire. And we’re really lucky that there were no disastrous fires in our region this year. Knock on wood.

But we know that fire is a new reality, and we’re going to have to learn how to adapt to fire in our midst. And the same with fog. The fog we take for granted. But without fog, this would be a much harsher place to live and work.

CHRIS EKSTROM: It’s an unpaid ecosystem service. Farmers would not have the same amount of water for their crops, and maybe not even be able to grow the same crops without fog. And redwoods get 40% of their annual moisture from fog. They don’t live where there’s no fog.

FRANS LANTING: So our view is that we need to build resilience into our man-made systems, and we also need to boost nature wherever we can, because when we can do that then nature will be a buffer. We need to help nature so that it can help us.

Lanting and Eckstrom will do two multimedia shows celebrating the “Bay of Life” project at the Rio Theatre on Saturday, Nov. 12 at 3 and 7pm; $25 general admission, $50 gold circle. Proceeds will benefit the newly established Bay of Life Fund. The exhibit at the MAH will run from January 19 to April 30. lanting.com.