Depending on who you’re talking to, the key ingredients traditionally used to craft a captivating work of fiction include character development, setting, plot, conflict and some resolution. For many great writers, it takes at least 350 pages. George Saunders can do it in 35 pages or less—and he does it artfully, with grace and panache.

“She was small and slight and her eyes were dark beads on either side of a beaklike nose. She moved quickly, head down, as if, we sometimes joked, scanning for seeds. She had a way of seeming to dart from place to place. She had a way, too, of saying the most predictable things.”

After reading those first three lines, we know a lot about the protagonist of “Sparrow,” one of the nine short stories in Saunders’ new collection Liberation Day. “Sparrow” spans a mere 10 pages, about 3,000 words. Saunders uses them with the care of a neurosurgeon; every paragraph is as lean as a giraffe’s neck, each sentence tighter than a sailor’s knot.

“My natural stride is more of a short story stride,” Saunders explains. “Kind of like wind up the toy, then try to get it to go under the couch as soon as possible.”

As with most of his short stories, “Sparrow” is a sprint to get under the couch. And that’s a fine place for a tale so tragically pathetic and uncomfortably ordinary.

Saunders’ first book of short stories was CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, published in 1996. Pastoralia was released in 2000, and In Persuasion Nation in 2006. Liberation Day marks his first collection since Tenth of December, which came out nearly a decade ago, in 2013. It was worth the wait. Like “Sparrow,” the other eight stories in the new book are familiar and haunting. Saunders paints portraits of real people you’ve probably encountered over the years—a concerned mother, a sad grandfather, “Sparrow”’s “everyday” woman looking for “everyday” love, an old-timer grappling with memory loss. The reflections Saunders casts of these real people have an acidic glow with an uneasy laugh on the side.

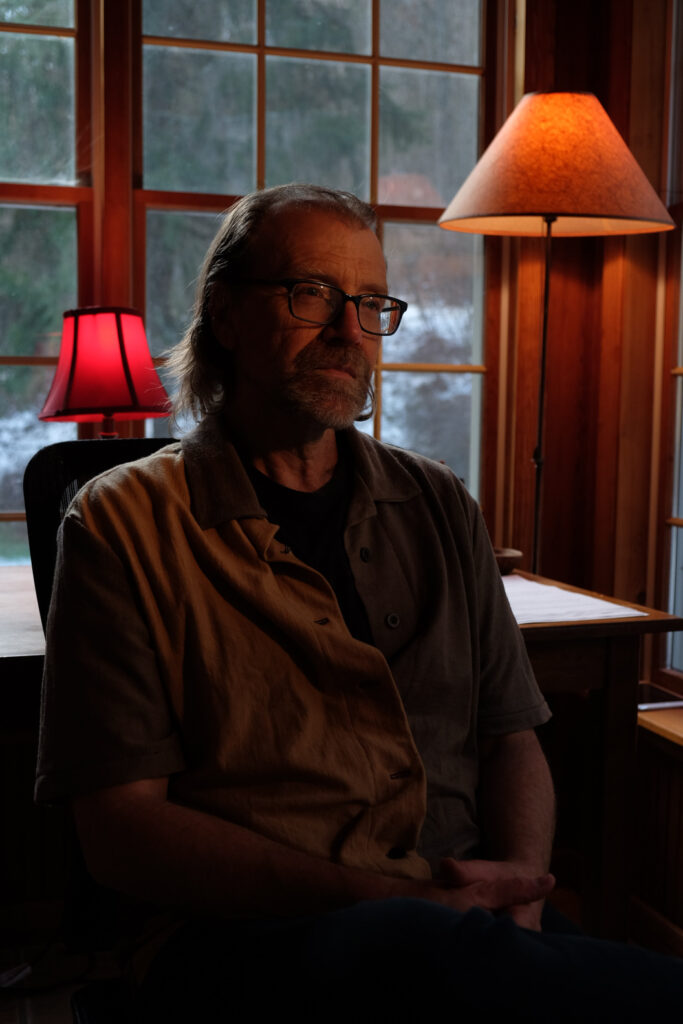

Since 1997, Saunders has taught in Syracuse University’s creative writing program. But it’s not a “those who can’t do, teach” situation. He’s published 12 books, including the New York Times bestseller and National Book Award finalist Tenth of December; the collection of short stories that won the inaugural Folio Prize in 2013, and the Story Prize. It also led to Saunders being named one of Time magazine’s Top 100 Influential People in the World in 2013.

In 2017, Saunders’ first and only novel thus far, Lincoln in the Bardo, debuted at the top of the New York Times bestseller list and went on to win the distinguished Man Booker Prize; it was also a Golden Man Booker finalist. The Bardo audiobook—which features a cast of 166 actors, including Carrie Brownstein, Miranda July, Ben Stiller, Jeff Tweedy, Susan Sarandon and Don Cheadle—snagged the 2018 Audie Award for “Best Audiobook.” Tina Fey, Michael McKean and Jenny Slate, meanwhile, are a few of many prominent voices in the audiobook for Liberation Day.

“How’s that for a great cast?” Saunders wrote in his newsletter. “I’m so grateful to these wonderful readers, and to the legendary [audiobook producer] Kelly Gildea for bringing this all together so wonderfully.”

Saunders has been dubbed the “godfather of the contemporary short story.” He has solidified his reputation as one of the American masters alongside Raymond Carver, Philip K. Dick, Shirley Jackson, Charles Bukowski and a few others.

For this interview, Saunders responded to my questions over email. As you will read, he put as much thought into crafting his answers as he does with anything else that has to do with the written word.

How do you know when you’re finished with a novel or a short story—not just the writing, but the self-editing that comes afterward?

GEORGE SAUNDERS: It’s just a feeling, to be honest. I go through the story again and again until I feel increasingly satisfied with everything in it. This process tends to happen such that the beginning sections get “done” first, and then that sort of narrows the choices as I near the end, if that makes sense. I’ve sometimes compared it to painting a floor (although I’m not sure that’s really a thing). But … you keep going back and touching up the room until the whole thing looks good to you. Then, at the very end, there’s just that area around the door. You give it one last swipe of the brush as you step out. In a story, it’s a feeling of being able to get through it with pleasure from start to finish—no hitches, no little bumps of resistance. With experience, I think a person can get better at feeling even the slightest bumps. And weirdly, those are places where the story is really trying to ascend to higher ground. It’s kind of amazing how hyper-sensitive you can get to your own prose.

After you complete a manuscript, do you have an “ideal reader?” Someone you trust to give you honest feedback that you take to heart, and whose opinion might inspire you to revisit something in your work that you would have never thought to change?

Yes, for sure: my wife, Paula. She is a very precise reader, emotionally—if I can move her, then I know I’m doing all right. We have, I think, the same idea about fiction: it should have heart and be about things that matter and speak to people at their best. The best note I ever got from her was when I gave her the story “Tenth of December” to read. I had to go out, and when I came back, she’d gone out, but left a note that said something like: “TEARS. Send it out.”

What was the most emotionally challenging work you’ve written?

You know, I have to say I don’t really struggle emotionally with stories. I mean, they sometimes make me feel things, of course, but the process is so repetitive and laborious that I often find myself feeling something early and then just recalling that feeling as I go ahead into subsequent drafts, like, “OK, leave this part alone because, remember? Last year it really moved you.” The main feelings I have while working are frustration when I can’t get something to work, or a growing confidence that the story might be good after all, or little bursts of happiness at a good joke or turn of phrase, and so on.

How do you think your writing has evolved since ‘CivilWarLand in Bad Decline?’

I’d like to think that I’ve grown more comfortable with life’s positive aspects. When I first started out, I was at a place in life where the big thing was the struggle to make a living. We had two small kids and no savings, etc. So, for the first time, I was like: “Dang, life in America can be brutal.” So that found its way into that first book, which is very dark. Then, over the years, that “biggest thing I was feeling” shifted, as, of course, it would. Sometimes (like in Tenth of December), I was feeling very grateful and found myself showcasing moments where people proved themselves capable of rising to difficult occasions. This new book is coming out of a different feeling—the feeling that sometimes systems work against people’s freedom. Sometimes, things don’t work out very well for reasons that are existential—we believe too much in ourselves and our own phenomenon, for example. And what then? And so on. So, in each book, I find out something new about where I was for the period of the writing. I don’t decide any of that in advance, but just try to write the tightest, funniest, most genuine stories I can, and then, at the very end, I read the book and get a feeling like, “Oh, so that’s what was on my (deeper) mind.” So, I just try to work hard and hope that my writing is developing and that it’s becoming more intense and is encompassing more of all that life is: good, bad, funny, grim, you name it.

I find your work to be very cinematic. It’s easy to envision where your characters are in your stories. The scenes in ‘Liberation Day’ are incredibly vivid, giving readers a strong sense of place. Has film informed you as a writer at all? If so, which films have resonated with you most throughout the years?

Well, yes, I was a real TV and movie kid and had some of my most formative, powerful experiences in front of screens—Jaws was huge for me, as were all the Monty Python movies, The Grapes of Wrath. Bicycle Thieves and also Get Smart and Green Acres and the Peanuts holiday specials and so on. I think that’s such a key moment: the first time a work of art blows the top of your head off, you go: “How did they do that? I want to do that.” And you absorb some of the qualities of that work. For example, when I was in seventh grade, I accidentally saw one of the Dirty Harry movies. It was way too brutal and violent for me, but … there I was, sitting there, too scared and captivated to move, and receiving the message (from the way I was feeling: Violence in a work of art can be powerful. I think that partly explains why my stories tend to be so dark.

You’re frequently described as a “writer’s writer.” What do you think is meant by that?

I think it generally means: “That poor guy doesn’t sell many books.” Haha. No, I like to think that it means that I write in such a way that other writers notice the hard things I’m attempting that non-writers might not notice. So, I like that. I’d prefer to be, you know, a reader’s writer. But I’m really happy to be considered any kind of writer at all. I remember that line Steve Martin says in The Jerk, as he’s trying to convince the Bernadette Peters character to go out with him. She tells him she already has a boyfriend, and he asks if it might be possible for him to come over and just, you know, watch her and her boyfriend fool around: “I just want to be in there somewhere.”

Do you have any rituals, habits or routines regarding your writing process?

Not really. I wrote my first book at work, and that was no place to be at all precious about the routine. I was just grabbing time where I could find it, at whatever computer terminal was open. I have two little framed things I like to have with me, one by Raymond Pettibone and a photo that one of my daughters took. But basically, I just sort of say to myself, wherever I am, “Go into that space now. Time is short.”

What’s the most common question hopeful writers ask you? What’s your answer?

They tend to ask about the one thing I’d recommend that would improve their writing, and I always advise them to learn to take revising very seriously—accept it as, really, the biggest thing a writer has to learn in order to start sounding like herself. Not just “fixing” problems but really learning to live in the world of the story by going through it again and again, line by line, making those thousands of micro-choices that really make the story sound like one of theirs—taking radical responsibility for every single phrase in the story. This is all about developing and trusting one’s own taste and accepting that iteration—going through the story again and again—is, really, a way of getting the hundreds of people that they are into the story. One day, we’re very tough on ourselves, one day easy; one day we’re serious, the next day funny. All of these writers get a chance to weigh in on the story if we’re patient in revision.

Is there any question(s) you wish aspiring writers would ask you, but never have?

“Mr. Saunders, where should I put this big bag full of money?” It’s funny, but they just almost never ask that one.

Bookshop Santa Cruz will present George Saunders reading from and discussing his new book ‘Liberation Day’ at 7pm on Tuesday, Nov. 1, at Veterans Memorial Building, 846 Front St., Santa Cruz. $34 plus fees. Ticket price includes one signed hardcover cover of ‘Liberation Day.’ bookshopsantacruz.com.